'The Baghdad Clock': A novel of Iraqi youth in search of lost time

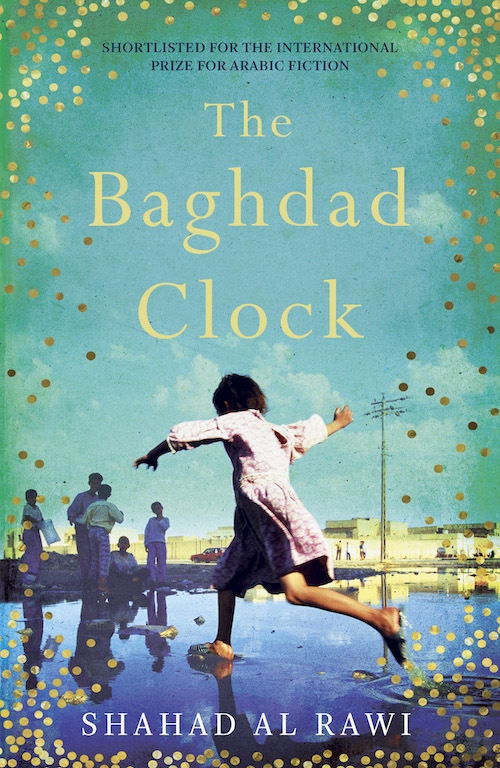

Shahad al-Rawi's debut novel, The Baghdad Clock, which won the First Book Award at the Edinburgh International Book Festival earlier this year, takes readers on a journey into the history of Iraq and explores how Iraqis deal with the traumas of the past - both recent and distant.

The Baghdad Clock evokes life growing up in Baghdad in the 1990s and 2000s through the eyes of a young unnamed female protagonist. The world she knows is irrevocably changed in the aftermath of the 1991 Gulf War when US-led troops drove Iraqi forces out of Kuwait.

The UN economic sanctions imposed in retaliation for Iraq's invasion of Kuwait weigh heavily on the characters in the book. They gradually sap the narrator's neighbourhood of life, colour, and eventually people, as families emigrate in search of better lives.

Baghdad for me at this time is a paradise idea of my childhood more than a real city

- Shahad al-Rawi

Speaking to Middle East Eye from her current home in Dubai, al-Rawi, 32, explained that it was hard for her to come to terms with the violent upheavals that overtook her home city in the years since she left, which was in the early 2000s.

"Baghdad is a vibrant and wonderful city, but as you know it has been hit by successive disasters for decades," she said.

Al-Rawi has visited Baghdad only a few times since leaving, the latest was a short trip in 2016 for a signing ceremony. The Baghdad she knows is the one she grew up in before the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, and the destruction that followed.

"Baghdad for me at this time is a paradise idea of my childhood more than a real city."

The narrative captures the idea of an imaginary city with elements of magic realism as the young protagonist attempts to come to terms with the changes taking place both in her own life and in her country.

Nadia, another young girl who lives in the same neighbourhood, provides the earliest form of escapism in the novel. She meets the protagonist in an air raid shelter and they become friends. The protagonist then begins entering Nadia's dreams and fantasising about breaking out of the restrictive environment of sanctions-stricken Iraq.

"Cities change and the social cohesion changes too in normal circumstances, let alone the conditions of a city like Baghdad," explains al-Rawi.

"Sooner or later, this ship will sink with all of you on board," he tells the women of the neighbourhood who gather to hear his premonitions.

He alludes to the looming emptying of the neighbourhood as the sanctions and wars take their toll and the community slowly disintegrates, seeing no future for themselves in their beleaguered nation.

"You will warm yourselves with memories. This neighbourhood of yours will become nothing more than a song you weep to remember. I see you on dark, lonely paths, as you wander, lost, as exiles do.

'Overcome the past'

The past has encroached upon al-Rawi in other ways as well. Following the announcement of her win in Edinburgh, some social media users began to highlight a number of comments she made on Facebook and Twitter in her early 20s, including one in which she appeared to praise Saddam Hussein, the former Iraqi ruler who was executed in 2006.

"A Lebanese, Egyptian and Saudi rap song for the hero Saddam Hussein," she wrote, while posting a pro-Saddam Hussein rap track on Facebook.

"May Allah bless you, my master. We can't forget you. Salute to you, our martyr and beloved one."

As the outcry mounted, and with accusations that she was a supporter of Saddam's now-banned Baath Party, she deleted her Facebook and Twitter accounts.

Shadow of Saddam

Despite her earlier comments, al-Rawi denied to MEE that she was a supporter of Saddam, saying that the comments on the rap song had been a joke, while the others simply reflected her inexperience.

"I was in the situation of a girl displaced from her country and her city and who was not at this level of maturity and awareness that I am now," she explained. "I left Iraq at the age of sixteen. I lived mostly in the years of siege, and then I witnessed the US occupation of my country and the destruction of its infrastructure. I had not a clear political opinion in the events rather than reactions at a time of deep discrepancies and social violence."

Artistic and literary creativity is an individual work, but without modern institutions it will have to encounter great difficulties

- Shahad al-Rawi

The social media attacks began after The Baghdad Clock was shortlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in February. According to al-Rawi, they are attempts by her opponents to "break my morale".

"Some demands have reached the extent of demanding my assassination and threatening the life of my family," she said.

"Such things should be taken seriously in a country that has witnessed similar incidents in [broad] daylight," she said, in reference to a recent spate of killings of high-profile women activists and social media figures in Iraq.

"Although I am a strong and self-assured person, all the previous campaigns have not broken me, and I will not be defeated by other campaigns that I expect in the future," she added.

The shadow of Saddam Hussein, who oversaw the deaths of hundreds of thousands of his own people, including acts of genocide against Iraqi Kurds as well as launching a war with Iran in 1980 and invading Kuwait, still polarises much of the debate in Iraq. While many still view him purely as a brutal dictator, others - even his former foes - have grown nostalgic for his reign, which, though authoritarian, nevertheless saw a degree of stability and security.

Though The Baghdad Clock has few references to the Iraqi ruler, there is one grim passage which sees the elderly Uncle Shawkat - who gradually descends into senility as the book progresses - abducted by the security services under suspicion of being a spy due to his increasingly erratic behaviour. When returned seven days later, he is humiliatingly adorned with a picture of Saddam hanging around his neck.

"You know that the regime of Saddam was dictatorial, individual and totalitarian at the same time," said al-Rawi. "A writer who is devoted to human values cannot bear any positive emotions towards him."

'A broken machine'

Al-Rawi's characters in The Baghdad Clock are mostly middle-class women and girls and the story is driven by their experiences of hardship, love and dreams of the future.

One character suggests the main intention of the sanctions is to empty Iraq of its middle class, as they are "the children of the state, and if our class disappears, the state becomes a broken machine".

The women in the novel hold high aspirations and look towards going to college and becoming doctors or other professionals. They pass around a copy of Gabriel Garcia Marquez's One Hundred Years Of Solitude - an obvious point of reference for the novel's style - losing themselves in the novel's fantastical recreation of Colombia's past.

Their burgeoning sexuality is also touched upon; teenage romances, forged in the restrictive environment of sanctions-era Baghdad, linger long into adulthood, leading to broken hearts and regret over lost opportunities. As with much of the book, their early loves, both human and geographical, are idealised from a more jaded present.

The threat of patriarchal violence rears its head at one point. One of the girls in the neighbourhood, Mayada, is shot and killed by her brother Hussam - for unclear reasons - after she tells him she is planning to get married. This is a tale recounted to the main protagonist in one of Nadia's dreams.

Later, after fleeing the country, he returns as an "opposition" politician following the 2003 US-led invasion. Upon returning to the house where he murdered his sister, Mayada's ghost appears to take vengeance on her brother.

In contemporary Iraq, the dangers of being an outspoken or prominent woman have been highlighted by a number of recent killings.

The murder of a number of beauticians this year, including Basrawi human rights activist Suad al-Ali and social media star and model Tara Fares, has raised fears that women who attempt to put their heads above the parapet may face abuse, threats or even death.

Al-Rawi said that social media, in particular, was becoming a hub for the spread of misinformation and incitement.

"There is a cultural environment that encourages these crimes and triggers campaigns of criticism and defamation against any person having a different lifestyle using social media websites. Young men were subject to this also, and young women too," she said.

"Investigations into the recent crimes did not produce results, but the government accused so-called extremist militants, as it called them. We have a long way to go in order to learn how to tolerate difference and respect the lives of others."

Future hope

Although Iraq has only recently emerged from the war against the Islamic State group, and Baghdad is still recovering from years of violence and corruption, al-Rawi said that she was optimistic about the future of her country, pointing out there was "a large number of talented young people in various fields, especially literature and art.

"However, the country still lacks the infrastructure for cultural production, theatres, film companies and professional publishing houses that have an institutional plan of action, in addition to translation and marketing. Artistic and literary creativity is an individual work, but without modern institutions, it will have to encounter great difficulties."

If you are wondering whether there is still hope and if I’m optimistic then, yes, because the current situation in my country is much better now than 2010

- Shahad al-Rawi

The Baghdad Clock, the iconic building that forms the centrepiece of the novel, was destroyed during the 2003 invasion of Iraq; however, it was later rebuilt. Although much of Iraq's social and cultural life was destroyed in successive conflicts, al-Rawi remains hopeful for a cultural revival.

"If you are wondering whether there is still hope and if I’m optimistic then, yes, because the current situation in my country is much better now than 2010," al-Rawi said. "Things are improving but slowly, and successive governments have to invest a lot of effort on infrastructure, education and health.

"We need real community reconciliation to overcome the past."

In al-Rawi's The Baghdad Clock, the soothsayer also offers a glimpse of hope and advises Iraqis to recreate their history beyond the destruction.

"Geography is a fate that cannot be escaped, but history is made. Adapt to your geography and change your history."

The unnamed female protagonist replies: "How do we change history? Do you mean falsify it?"

"Not at all," answers the soothsayer. "Just weave from its cloth a new garment. Gather the good islands together and leave out the painful ones."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].