Modern spin of 'The Pit and the Pendulum' puts Iranian woman at centre stage

LONDON – A female prisoner wearing a chiffon white headscarf sits in the centre of a near-bare stage as flickering images of Iran from before the Islamic Revolution of 1979 illuminate the backdrop.

We don’t know what her crime is or who incarcerated her, but we know that she is terrified and enraged. The opening scene of the modern theatrical adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Pit and the Pendulum at the Omnibus Theatre in London is about as close as it gets to the original macabre short story, which was first published in 1842.

Poe's version, set during the Spanish Inquisition, describes in excruciating detail the psychological and physical torture endured by a political prisoner who wakes up in a pitch-black vault after being handed a death sentence.

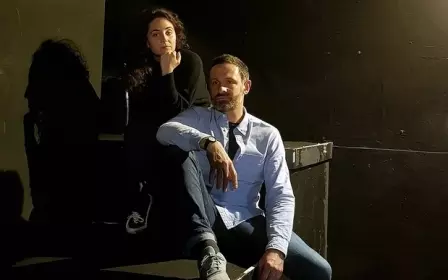

In this reimagination by British playwright and director Christopher York, we quickly come to learn that Tehran replaces Toledo; an Iranian feminist replaces a protagonist who is often depicted as male and white; and post-Islamic Revolution Iran replaces the Spanish Inquisition.

“The majority of my time spent on stage is telling stories from the perspective of a white, Western man,” York, who is an actor himself, told MEE. “When I'm behind my laptop or in a library, the liberation of a playwright is that I can explore new continents, cultures and characters, the lives of people I would never get to explore as an actor. That's the joy.”

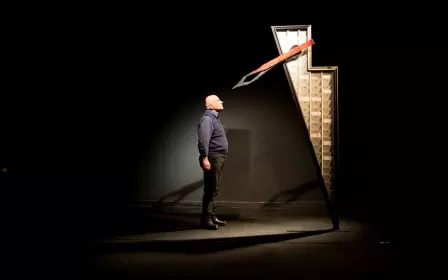

The darkened stage at the Omnibus Theatre in Clapham is occasionally brightened by a digital image of a swinging blade - the pendulum - which hovers over the actor as she stumbles while desperately exploring her filthy surroundings. Audience members are given headphones to wear that deliver binaural or 3D stereo sound design, offering the illusion of a more intimate experience throughout the performance.The dizzying and at times jarring reimagination, which opened on 6 November and will run through 24 November, pays homage to the original tale while flipping it on its head. Despite its “delicious gothic thematics,” York says he chose to adapt The Pit and the Pendulum because its themes are “crazy universal”.

Piercing critique

Though the storyline is broadly similar – a prisoner relays their panicked thoughts while being held in solitary confinement – The Pit and the Pendulum is more a piercing critique of the eponymous story by Poe than a straightforward adaptation of it.

The majority of my time spent on stage is telling stories from the perspective of a white, Western man

- Christopher York, playwright and director

This ambitious approach widens and modernises the scope of the original story’s motifs. The lead is most certainly nuanced. She is fearless and fearful at once, and her grievances are many: she battles repression and misogyny in her homeland, while also lamenting sexism, colonialism and imperialism in the rest of the world.

“The West, especially Western news outlets, present the Middle East in a very black and white way,” York said. “Post 9/11, we have delved into demonisation and stereotypes, and so much of my research has been about moving away from the archetypes that prevail our media and instead outsourcing more complex presentations of this, quite frankly, beautiful part of the globe.”

Although there are no gendered pronouns in the original story, most takes on The Pit and the Pendulum, including a 1961 film, feature a white male lead. York challenges that narrative not merely by casting Dehrouyeh, but also by having her character engage in a one-way intense conversation with Poe, who occasionally makes an appearance by way of a haunting voiceover performed by actor Nicholas Osmond.

Though Osmond narrates Poe’s short story and is not speaking to Dehrouyeh, she speaks back to him as if it were Poe himself, not his creation.

Deyrouneh’s character is exasperated by his interventions, which she views at best as an interference and at worst a manifestation of patriarchy, colonialism and oppression. She responds by furiously saying, “White man: I don’t need your comments!” and “I can chronicle my own tale!”

‘Different view’

“The picking of my protagonist was about which kind of human needs to drive this tale in the 21st century,” York said. “I wanted to present a different view, not just of her, but also the beauty of her home she is so desperate to return to.”

So often [Middle Eastern] women are presented on screen or stage as passive wives or terrorists...My protagonist is a badass. She is a hero. She could join The Avengers in a heartbeat

- Christopher York, playwright and director

“The hijab should be a choice not a symbol of oppression!” she exclaims to the audience, while manically recounting details of her incarceration. “There is nothing you can do to break me!”

The protagonist’s plight is rooted in reality. In February of this year, several Iranian women removed their headscarves while standing on telecoms boxes along some of the busiest roads in Tehran and elsewhere in the country, demonstrating against a state law that requires them to wear the hijab and loose clothing.

Some of the activists attached their white scarves to sticks, brandishing them in a show of peaceful protest. Police swiftly arrested 29 women for taking part in the demonstrations, spurring the hashtags #WhiteWednesdays and #NoToCompulsaryHijab on social media.

‘Badass’ protagonist

As the play progresses, the walls of the vault constrict even further, the swinging blade lowers incrementally, and rats infest the tiny space. In the centre of the room is a pit which the protagonist stumbles upon by mere chance, an ominous symbol of femininity, she speculates; while the pendulum, by contrast, is crudely “phallic”.

The hijab should be a choice not a symbol of oppression!

- protagonist

“So often [Middle Eastern] women are presented on screen or stage as passive wives or terrorists,” York said. “My protagonist is a badass. She is a hero. She could join The Avengers in a heartbeat.”

Dehrouyeh’s acting effortlessly switches between vulnerability and defiance. As her character descends into what can only be described as mania, she mumbles to herself in Persian, declaring at first that she is the “bringer of freedom to the city” and a “badass,” only to later state that hope can “kill” and that “one woman can’t start a revolution”.

The dialogue in York’s adaptation is occasionally hackneyed, featuring generous usage of millennial buzzwords and phrases including “patriarchy,” but it’s always relevant.

The director said his storytelling was inspired by films including, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night and The Breadwinner, in addition to the BBC documentary directed by Adam Curtis, Bitter Lake, and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, all of which deliver nuanced, well-researched views of the countries they’re set in or focused on.

‘Fighting subjugation’

Iran is perhaps an unsurprising choice for the setting shift. According to Amnesty International’s most recent country report, Iranian authorities continue to imprison “scores” of individuals who have voiced dissent in the Islamic Republic, while trials were “systematically unfair” and torture widespread. Women, in particular, continue to experience gender-based violence and entrenched discrimination in the country, with little to no protection, while human rights defenders continue to serve prison sentences.

The West, especially Western news outlets, present the Middle East in a very black and white way

- Christopher York, playwright and director

Political prisoners have been refused adequate medical care and are enduring inhumane conditions of detention, including overcrowding, limited hot water, inadequate food, insufficient beds, poor ventilation and insect infestations.

Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, a British-Iranian charity worker for the Thomson Reuters Foundation, has been serving a five-year prison sentence in Iran since 2016, after she was accused of being a spy by Iranian authorities, a charge denied by her and the foundation.

With that political context in mind, The Pit and the Pendulum is certainly timely, although it fails to replicate the claustrophobic atmosphere and sheer terror evoked by Poe’s original story. The promise of a “fully immersive experience” and an “exploration of sensory deprivation and isolation in a near pitch-black room” isn’t even halfway fulfilled.

“My role as I see it is to present a character fighting subjugation, in all her glorious complexity,” York said. “If there is a message, it's that our humanity should be the constant.”

The Pit and the Pendulum, from the Creation Theatre Company, continues at the Omnibus Theatre in Clapham through 24 November. A post-show Q&A with cast and creatives from the play will be held on 13 November.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].