Algeria: the difficult legacy of Hocine Ait Ahmed

ALGIERS – He was the last to incarnate both the struggle of national liberation and the uncompromising opposition to power. More than the disappearance of a political figure, the demise of Hocine Ait Ahmed at the age of 89 on 23 December in Lausanne, Switzerland, marks above all the end of an era.

First, the end of a generation. Out of the nine "sons of the Toussaint [All Saints Day]," as the leaders who started the war of independence against France on 1 November 1954 were called, he was the last one still alive. In 1947, he led the Special Organisation (OS), the paramilitary section of the independence party PPA-MTLD, itself the heir to the North-African Star of the 1920s, which was created when the nationalists lost their illusions regarding the possibility of a peaceful political struggle against France.

According to Oran University researcher Rabah Lounici, Ait Ahmed can even be regarded as “the first chief of staff of the Algerian army” since he was the architect and first leader of the Special Organisation.

“Like all those who came from this party, Ait Ahmed had the stature of a statesman,” Amazit Boukhalfa, journalist and consultant on historical issues, told Middle East Eye. “It is precisely because he had too much charisma that [Ahmed] Ben Bella was chosen in his stead to lead the country in 1962.”

About his extraordinary career – he quit the provisional government of the Algerian Republic to join the resistance only one year after independence, he was condemned to death, and went into forced exile for more than 30 years to escape prison - historian Malika Rahal, researcher at the French Institute of History of the Present (National Centre for Scientific Research), remembers something else: “It made it possible to understand that there was a real political life after independence. Ait Ahmed has nothing of a former fighter who only capitalised on his struggle in the Algerian revolution. With him, it is impossible to stop the history of Algeria in 1962.”

Historian Nedjib Sidi Moussa also reckons that if “history will remember him as a young revolutionary and an old opponent,” his political career “will nevertheless remain associated with his second life as a militant in the opposition,” he told MEE. It was a second life that started as early as 1963, with the creation of the Front of Socialist Forces (FFS) and the armed maquis (armed dissidents group against the central power under the banner of the FFS, it was based in the mountains of Kabylia).

“Ait Ahmed’s approach wasn’t marginal,” a leader of the FLN, the country's largest party, told MEE. Other "sons of the Toussaint," such as Mohammed Boudiaf, Krim Belkacem or Mohamed Khider, confronted the duo of Ben Bella-Houari Boumediene before going into exile. Belkacem and Khider were murdered.

“His stance, which consisted of denouncing the confiscation of independence by the military general staff, was largely shared by some founding fathers of the Algerian revolution. This is why the FFS was a sort of idealised FLN, the anti-state party, the anti-one party system, the anti-machinery of power. He wanted to pursue the revolutionary ideal by aiming at democracy as a second objective after 1962. Unfortunately, he failed because independence consecrated the victory of the military over civilian power.”

The FFS may have failed, but the party’s militants claim it in unison: “Hocine Ait Ahmed transcended the party and, through him, the idea of a democratic Algeria stayed alive.” They point out that the problem with today’s opposition “is to have participated in the government at one time or another - something that the FFS never accepted”.

Hakim Haddad, a former FFS elected representative who knew Ait Ahmed well, "Da L’Hocine" as he was called according to the traditional formula of respect addressed to an elder, told MEE: “He never abandoned his principles. As for any militant career, he had his highs and lows, but he never let himself be fooled by power. In that, he was different from the others."

Different from the others? His critics, however, have always reproached him with having reproduced “the kind of cult of personality” that he himself combated in either Messali Hadj, the leader of the Algerian national movement from the '20s to the '50s, or in presidents Ben Bella and Boumediene in the '60s-'70s.

For that matter, the media and politicians have for the past 10 years regularly raised the issue: can the FFS survive its charismatic leader? “This has undoubtedly disappointed many hopes in some militants,” said Nedjib Sidi Moussa, before moderating his comment: “But more than anything else, the development of the FFS has been affected by the political game, by repression and by terrorism.”

For Malika Rahal, a political assessment of Ait Ahmed’s legacy should lead “to a political debate about what today’s opposition is”.

“For example, assessing the maquis of 1963: was it the right time to do that? Hasn’t it contributed to endangering the country? We must also ask: how far can the opposition go? To oppose whom: the regime [of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika] or the state? What should we safeguard? And also, we should raise the question of the nature of opposition parties: are they capable of developing models which are really democratic?” she asked.

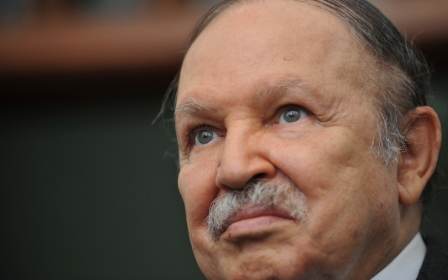

President Bouteflika announced an eight-day period of national mourning to pay homage to Hocine Ait Ahmed.

This article was originally published on Middle East Eye's French page

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.