Barricades, tents and community: A guide to Sudan's sit-in

Holding their fingers up to form peace signs, protesters reaching the barricades around the sit-in at the heart of Sudan's revolution raise their arms to be searched by groups of volunteer guards.

Without a hint of irritation, they go through the safety measures several times, smiling, sometimes dancing every time they reach one of the makeshift checkpoints built from rocks, scrap metal and upturned dumpsters.

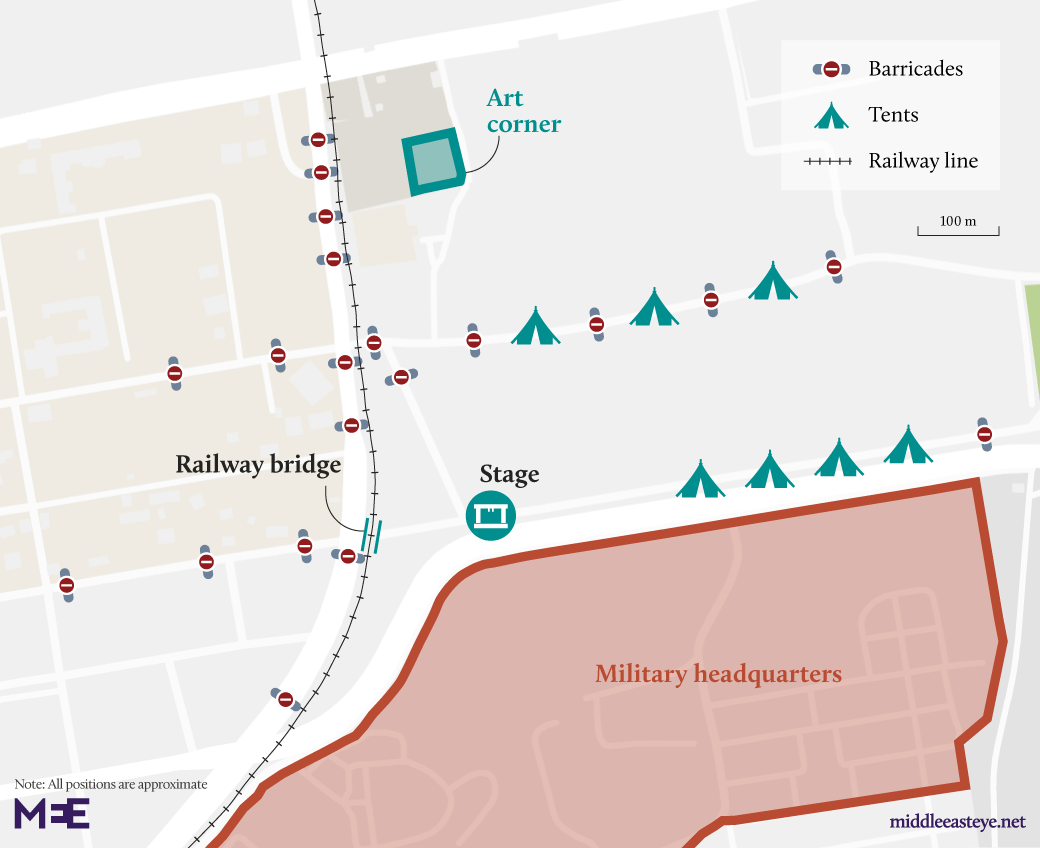

The barricades went up a month ago to protect the sit-in that has occupied the sprawling space outside Sudan's military headquarters, where protesters successfully demanded the exit of three-decade ruler Omar al-Bashir - and now want the military who ousted him to hand power over to a civilian government.

Images from the sit-in fail to illustrate the sheer size of the protest area, which can span around a mile and is regularly filled with tens of thousands of people on any given night.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Beyond the barricades are a scattering of rallying points and a main stage, tents for the protesters, hubs for artists, medical services and spaces for prayer and breaking Ramadan fasts.

For many, it has become a community that represents the new Sudan they want to see.

The barricades

During the early days of the sit-in, it was common for Bashir's security forces to raid the site, beating the protesters and firing at them, leading to gun fights between Bashir's security and low-level soldiers stationed around the sit-in who had sided with the protesters.

That quickly led to the erection of the crude barricades, aimed at stopping vehicles used by paramilitaries still loyal to Bashir from entering.

Mohammed Abbas, 21, is one of the young Sudanese who man those barricades, searching everyone who enters for weapons and apologising for the inconvenience.

"These barricades are for security, for all the people," he said, describing how, in the early days of the protest, militia fighters regularly tried to enter the protests without uniforms and with concealed guns.

"Now the situation's better...these barricades are so important."

The 'heartbeat'

Most of the half-dozen checkpoints protesters have to pass through to enter the sit-in open up on a central junction, where the sound of iron and steel being clattered has become an unmistakable soundtrack for the protest.

"This knocking is like the heartbeat of the collective," said Abdulraziq, 19, from southern Sudan.

He and others sit atop the railway bridge in the middle of the protest, banging its sides and striking the railway lines to create a never-ending rhythm for the protest movement, to rally demonstrators passing through.

In the tunnel underneath, more youth strike a different rhythm on sheets of scrap metal; the sounds meld chaotically and the youth see it as a way to signal their resistance to the military council now running the country.

The military headquarters

On 6 April, the anniversary of the last successful Sudanese uprising in 1985, the protesters who had been demanding Bashir's resignation began their sit-in outside the military headquarters in the capital Khartoum.

The pressure eventually led to military leaders intervening and ousting Bashir - but protesters have demanded that power be handed over to civilians, not kept within the military council the generals had set up.

So the protesters have refused to move. Throughout the night when - especially during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan - the numbers of protesters multiply, groups of hundreds of youth shuttle up and down alongside the fence of the military headquarters.

"Fall, or no fall, we stay here," they chant, stopping momentarily outside the base's gates, facing the soldiers standing guard.

The image is replicated throughout the protest area, where demonstrators spontaneously burst into chants or charge from end to end, picking up others along the way.

Impromptu speeches or political poetry readings happen on little stages throughout the site, while a large main stage in the centre is used for concerts or to play films documenting the whole protest movement, which began in December.

The tents

As the sit-in endured, tents sprung up. They belong to various groups of workers who organised to attend together, civil society groups who have been galvanised by the movement and camps of Sudanese who have travelled to the capital from cities further away.

Each proudly declares the city they travelled from to join the sit-in, creating a common space for the many ethnic groups of Sudan who felt they were divided under Bashir's rule.

Outside these tents, and in any free space available, green weaved mats are laid out just before sunset every day. Fasting protesters, drained of their last ounces of energy, gather around to share bowls of traditional meals cooked in makeshift kitchens and excite themselves over the chance to quench their thirst with some of the treasured drinks exclusive to Ramadan. Afterwards the mats, set in rows, are cleared away and used for Ramadan's nightly Taraweeh prayer.

Women selling ginger-infused coffee, tea and Sudan's beloved hibiscus drinks set up for the night, starting up their fires and putting out stalls, benches or simple rugs for their customers.

"I haven't been outside [of the sit-in since it started] so I don't want to know what it's like outside, but the life inside here is better," says Fatima Ibrahim, 30, who started selling coffee in Khartoum after fleeing conflict in the western Darfur region, where Bashir is accused of war crimes. "Thank god, we've managed to change the situation a bit."

The art corner

Hidden away in the northern end of the protest is a corner many have come to cherish. Artists who felt restrained under Bashir now welcome the freedom they have found within the sit-in, painting the walls, setting up exhibitions and putting on nightly performances of art and theatre.

"We've been suffering for so many of years from not being free," Arif Ibrahim, a photographer exhibiting his pictures, told MEE. "This is the opportunity to show the art and be more open about our art and ideas and send a message."

"We've been suffering and it's time to make a break. It's a new Sudan. For artists and for [all] citizens too."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.