'Did you bring cigarettes?': Meet the SDF fighters on the frontline in the Islamic State's last refuge

Aggressively waving his arms in front of a battle-scarred building, a fighter has one thing on his mind.

“Food and cigarettes. Did you bring any food or cigarettes? Where the hell are the supplies?” he shouts, as his companions emerge from what was once the home of an Islamic State (IS) family.

Now the building is occupied by Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters, who have taken it as their position near the frontline.

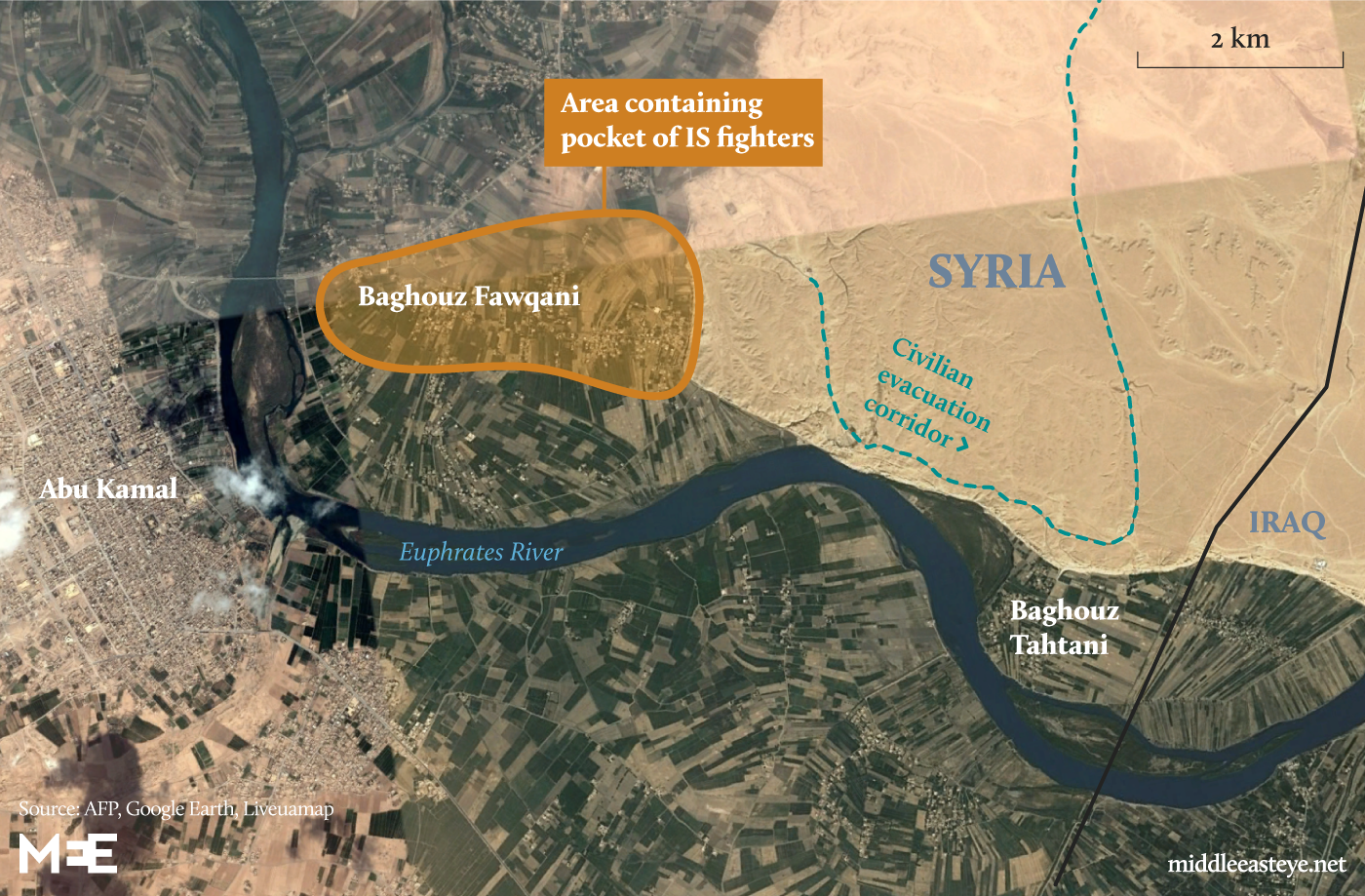

The unit moved to this spot in eastern Syria’s Baghouz a couple of days ago, after the US-backed SDF militia rolled the few remaining IS fighters into the last remaining pocket of territory they hold in the country.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

A kilometre away, the battle rages on.

But here in the remnants of what was likely a militant’s home, Kurdish fighters feel vulnerable and forgotten.

They fear regular nighttime IS ambushes, either carried out by sleeper cells or militants emerging from hidden tunnels.

The fighters also complain they have been left without any further instructions and - more pressingly to these fighters – without any food and nicotine for several days. A soldier illustrates the number of days he has gone without either by holding up four fingers.

“Look. This is how we are being treated,” another soldier says, placing a large rock in his waistband to demonstrate his recent weight loss.

Quickly the fighters’ voices rise and rise, until a commander of a nearby unit, Abu Dawla, as he is called, intervenes and promises their situation will improve soon.

Once the fighters are quietened, 27-year-old Abu Dawla moves on, taking Middle East Eye through areas of Baghouz that just days ago were populated by the final few hundred IS militants and their families.

Little known outside of Deir Ezzor province, even by many Syrians, Baghouz has become IS’s last refuge in Syria – and they are losing more of it hour by hour.

Villages more dangerous than the frontline

To get to central Baghouz, travellers must pass through an expanding collection of towns that the coalition have left deserted and in partial ruins in recent weeks.

Despite this, civilians have already started to return. But, an SDF officer explains, this has made them more dangerous than the actual shelling, recurrent air strikes and fierce fighting happening at the frontline.

“One thing is the frontline. That is something we can control. It is far worse with the newly liberated cities. All the civilians returning here are supporters or families of ISIS. The villages give the sleeper cells a range of possibilities to carry out operations and ambush-attacks,” Haval Ciyager Amed, a Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG) press officer under SDF command, explained.

Along the way is Hajin, a village that had become the de facto IS capital following the capture of Raqqa in 2017. Supporters and relatives of IS members have sought refuge here, fleeing the coalition’s advance, and driving through is a tense experience.

By the side of the road, a man on a motorbike, splashed with mud by a passing minivan, kicks the vehicle repeatedly in frustration.

“Sometimes, they do it on purpose. Either to slow us down or just to bother us. Tactically, ISIS have suffered a blow, yes. But as a system, they have not been defeated,” he said.

But there is also a lingering concern among those travelling in the van that wayward strangers by the road could be militants, poised for an ambush.

Every day, ten years older

In lower Baghouz, street after street is completely abandoned, save for bombed-out houses and crushed mosques, piles of rubble and personal belongings strewn across a landscape left in haste.

“Look at this,” a soldier says, lifting a black and white IS flag from the ground and dragging it along the earth.

“Listen guys. Don’t let the banner touch the ground. It is haram (forbidden) when the name of God is written on it,” said Qandil, 25, an SDF field commander.

In a small front yard littered with blankets, schoolbags, children’s shoes, clothes and a picture in a frame, Qandil kneels down and discovers two copies of the Quran in the dirt. One is in Russian, the other in Arabic.

“ISIS have sullied Islam. They have nothing to do with our religion,” he says, lifting both up and kissing them before gently leaving them on a pillow as the tour of the town continues.

Abu Dawla and Qandil, who are both from Hassakeh, joined the war against IS voluntarily.

“I wanted to revenge my uncle. He was killed by ISIS. And I wanted to serve my country,” says Qandil, who became a soldier when he was still a teenager.

Despite his dedication, he admits that he would much rather hang out with his girlfriend, picking her up from school and going to a cafe as they used to do. He has yet to finish a degree he started before the war.

The two joke as they move closer and closer to the frontline and gunfire and mortar strikes grow louder. Soon a casual conversation turns into a tour of traumatic wartime memories.

“We buried a man and a woman right here. ISIS. They were killed. Whenever we find their bodies, we have to bury them,” Abu Dawla says, pointing to two graves marked by a few stones.

“Over here, we were attacked by another man and women. You can actually see the blood right here. The woman was wounded in the arm. Everybody is taking up arms in this war,” he continues.

“Every day we participate in this war, we get ten years older,” Qandil adds.

He says he hasn’t seen his family in more than three months or spoken with them on the phone. When they ring him at the frontline, he never picks up.

“It will only cause more troubles for everybody if I do,” he says.

'Dawla', drones, and Real Madrid

Along a path through the village, there is a drone, or what’s left of it. Nearby in a patch a grass, a Coalition leaflet, dropped from a plane, promises food, freedom and survival.

The soldiers sweep and comb the terrain, filling their hand and pockets with odds and ends discovered along the way.

In the skeleton of a building that once stored military equipment, there are piles of brand new gas masks, army vests and uniform belts, a wet suit and camouflage.

Three days earlier, an arms depot was destroyed, leaving behind piles of Kalashnikovs, melted rocket-propelled grenades, handguns and automatic weapons and boxes of ammunition of all sizes.

IS militants stole the weapons from the Syrian Army’s 17th division when the group seized Raqqa in 2014, the soldiers said.

And there is graffiti everywhere.

“Dawla (the state) will return,” promises the writing on the wall of one building. An IS logo is pictured on another, right next to a note that says ‘H heart M’. Another insists: “If you are a supporter of Real Madrid, then be proud. If not, go kill yourself.”

Abu Dawla enters a small shop with only shards left for windows.

“It served as a blood bank,” he said, scanning curiously at boxes containing medicine stocks and needles, a variety of painkillers and ready-to-use bags of blood.

The wander through the deserted town is abruptly disturbed by a soldier yelling from the turret of a fast-moving Humvee.

“Move, move. Get out of the way,” he yells, as the vehicle carrying a wounded soldier, dimly lit from a head torch, whizzes by. In the sky where the sun is about to set, a plane or a drone drops something that explodes nearby.

As the day comes to an end, so has the pack of cigarettes in Abu Dawla’s pocket, leaving him bitter without his fix and reminding him of angry comrades who await his promise of supplies.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.