Gaza 2020: 'Our worst nightmare is when it starts raining'

The United Nations issued a report seven years ago warning that by 2020, the Gaza Strip could be uninhabitable due to severe problems with its water, power, healthcare and education systems.

Today, on the eve of 2020, MEE spoke with a homeowner, a doctor and a teacher about how their lives have changed in recent years - and what the future may hold.

The homeowner: Aisha Abu Nemer

Aisha Abu Nemer, 23, lives with her husband and three children - aged eight, six and eight months - in Khan Younis in southern Gaza.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The shabby house, located in a marginalised, poor neighbourhood, is 50 square metres in total and topped with a tin roof. The family lives in one room, which serves as a living room, kitchen and toilet. In an adjoining, single bedroom where all the family sleeps, there is a mattress on the floor and a white closet, the only piece of furniture in the home.

None of this protects Aisha Abu Nemer and her family from Gaza’s heat, cold or damp.

“Our worst nightmare is when it starts raining,” she tells MEE. “We have to get up at midnight to fill buckets with the rainwater that floods the house and remove the mattresses and blankets from the floor.

'It would cost us a lot to get a municipal water supply. So our neighbour fills our water barrel every now and then for bathing and washing the dishes and clothes'

“You can imagine that we have to always stay awake until it stops raining and the blankets dry.”

It was not always like this. When she and her husband, Jihad Abu Nemer, married eight years ago, Gaza’s economy was in better shape.

“My husband collects concrete on a laden cart and sells it for around 5-8 shekels [$1-$2] a day. That’s around 100-150 shekels [$29-$43] a month, which absolutely cannot cover our needs. That is why we mainly depend on aid.

“Eight years ago, he used to earn much more,” she adds, noting he earned around $100-$150 a month back then.

According to UNRWA, the UN agency that cares for refugees, years of conflict and blockade have left 80 percent of Gaza’s population dependent on international assistance.

Essentials are hard to come by. “We do not get tap water,” Nemer says. “It would cost us a lot to get a municipal water supply. So our neighbour fills our water barrel every now and then for bathing and washing the dishes and clothes. As for the drinking water, we fill another barrel from a water tap installed by a relief society in the neighbourhood.”

Despite her dire economic situation, Abu Nemer’s first priority is to get her six-year-old daughter a proper education.

“My daughter is in the first grade. She only has one dress for school. Once she gets back from school, I wash it and put it in the sun so that she can wear it the next day.

“Even if we did not have enough money for her education, I would sell my blood to send her to school.”

The doctor: Abdullah al-Qishawi

Abdullah al-Qishawi, 49, has been a doctor for more than two decades, and has been supervising Gaza’s first kidney transplantation project, launched in 2013.

At the dialysis department of Gaza City’s al-Shifa Hospital, the largest medical complex in Gaza, Dr Abdullah al-Qishawi does his rounds.

Qishawi, who is the head of the department, is checking on dozens of dialysis patients, many of whom have experienced a serious deterioration in their health since the start of 2019, due to a lack of medical equipment and electricity cuts.

The effects are evident in the overcrowded department. Rooms and beds are all full, forcing many patients to wait long hours - sometimes outside - for their turn on the dialysis machines.

“We are experiencing an aggravated crisis of medicine shortage and electricity cuts that complicates the treatment of dialysis patients,” Qishawi tells MEE.

The number of people needing treatment is also on the rise.

“What exacerbates the situation and doubles the number of dialysis patients is the fact that almost all the drinking water in Gaza is undrinkable. Thus, tens of thousands of people are harming their kidneys.”

There are 65 dialysis machines in Gaza, but just under a third of them are broken, Qishawi says. The Palestinian health ministry is unable to replace or fix them due to a lack of spare parts.

The dialysis department used to operate for 16 hours a day, from 8am until midnight. Now, to deal with the increasing number of patients and lack of medical staff and equipment, it has been forced to extend its hours until 4am.

“There is a severe lack of medical supplies and equipment, rendering the largest hospital in the enclave unable to provide the necessary and often urgent treatment to thousands of patients,” Qishawi says.

“The situation has significantly exacerbated during the past few years. If it continues this way, we will be witnessing a real catastrophe at all levels.”

And Qishawi has little hope for the future.

“There is no doubt that, although the situation has always been bad under blockade, we are witnessing the worst period in terms of medical services and the overall health situation [of Gaza residents].”

The teacher: Basema al-Basous

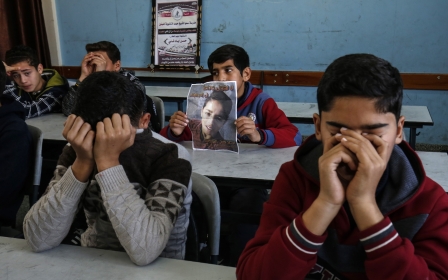

Basema al-Basous, 44, is a teacher at al-Abbas elementary school in the densely populated Shujayea neighbourhood of Gaza City.

In an Islamic studies class, Basema al-Basous, who has been a teacher for more than nine years, gives a Quran recitation lesson to 50 female students.

“Managing a classroom with 50 students is one of the most challenging things I’ve had to deal with since I first became a teacher,” Basous tells MEE.

“It’s difficult for both teachers and students to be in such an overcrowded place. I frequently suffer from hoarseness because I have to raise my voice to make myself heard to 50 children.”

The problem of overcrowding in Gaza’s schools is well recognised, with the population having grown by around 20 percent during the past decade.

Many educational facilites are forced to operate double shifts to cope with the influx. The Palestinian education ministry has said that 86 new school buildings must be built, and more than 1,000 classrooms added to existing buildings by 2021 to provide a safe and adequate learning environment.

Basous says her classes have been growing over the past few years, as parents have moved their children from private schools to government ones for economic reasons.

She agrees that building new schools and providing better equipment - including ventilation and heating systems - would be a step forward for Gaza’s education sector.

The overcrowding can also affect children’s health and productivity.

'If one morning a student who has the flu attends class, the next morning, there are about 30 other students who are infected'

“If one morning a student who has the flu attends class, the next morning, there are about 30 other students who are infected,” Basous says.

“In addition to that, the chaos and lack of chairs and desks - as well as the limited time - all reduce students’ productivity, comprehension and social harmony.”

She says she aims to “build a bridge of love and trust” with her students to help manage the extra load. But some of her colleagues struggle due to the noise and the difficulties of communicating with such a large number of students, she adds.

And she remains hopeful that the territory will be able to overcome its economic and humanitarian crisis.

'Palestinians in Gaza have their own way of resilience, that they can overcome their crises and live under the most difficult situations'

“I do not believe Gaza will be unlivable at any point in time,” Basous says. “Palestinians in Gaza have their own way of resilience, that they can overcome their crises and live under the most difficult situations.”

Until the education ministry tackles the problems at Gaza’s schools, she adds, “We will continue our personal initiatives and efforts to support our students.

“We cannot let them down, whatever happens.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.