Iraqi Kurdish students threaten more protests if government reneges on funding

Kurdish students at public universities halted a weeks-long protest movement after authorities promised to resume financial support in the new year, but told Middle East Eye they are ready to go back to the streets if necessary.

Their protests began on 21 November, with calls for a monthly stipend of around $50 per student to resume and, more broadly, over growing dissatisfaction with unemployment, nepotism, and lack of services.

'There are some mafias that govern the country. We will continue protests later, even if the protests stop now'

- Awder Mohammed Ameen, protester

Up until 2014, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) supported the students financially. But then the region was hit with a financial crisis and, like the rest of Iraq, faced war with the Islamic State (IS) group.

But now Kurdish youth believe it’s time they were supported once again. The KRG, they point out, is benefiting from higher oil revenues than in recent years and Baghdad paid Erbil $137.2m in July after years of budget cuts.

And they appeared to have achieved a victory last Tuesday when the KRG promised to provide $5m each month to assist students at public universities starting at the beginning of the year.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

While protests partially continued in Sulaymaniyah the next day, there have been no protests since.

Mera Jasm Bakr, an analyst and non-resident fellow at the German Konrad Adenauer Foundation, told MEE that protesters have temporarily stopped their demonstrations to see if the government will implement its promises.

Frustrations mount

Even before the student protests began last month, there were clear signs of bubbling dissatisfaction among young Kurds.

Many Kurdish youth boycotted the Iraqi elections on 10 October, including the Kurdistan regional vote. In November, just ahead of the protests, came the repatriation of over 400 migrants, including dozens of young people, from Belarus to Erbil after they failed to reach Europe.

Harun Tahsin, a 19-year-old who was at the Erbil International Airport on 19 November returning from Belarus, told MEE that he left for Europe to find a job because he saw little opportunity at home.

“If I find any safe way, I will try to go again,” he said.

Students out on the streets protesting expressed similar concerns over bleak prospects and called for reform.

Awder Mohammed Ameen, 21, a student in Halabja, was among a dozen students who blocked the road from Sulaymaniyah to Halabja last Tuesday.

He complained that the sons of Kurdish leaders in the Kurdistan region study abroad and "drive around in Mercedes, and spend thousands of dollars in Europe, but cannot give stipends to poor people".

He also blamed the KRG for failing to provide services such as electricity and water, after 30 years of rule. “There are some mafias that govern the country. We will continue protests later, even if the protests stop now,” he said.

Mohammed, another young student from Halabja, said demonstrations would carry on until authorities acknowledged their demands.

“We came here to ask for our rights, we proposed some good demands, but our main demand has not been implemented and not taken seriously,” he said. “Until they implement this demand, we will not give up.”

Savan Abdulrahman, a university graduate who participated in the protests, said that the main issue is that young Kurds see little employment opportunities before them.

“Since 2013, no one is employed by the government,” she said, suggesting that only those with relatives in the government get jobs.

“People in general are so hopeless for change that they just want to flee abroad and have a better life.”

'The public sector cannot absorb more employees, and there is no private sector'

- Mera Jasm Bakr, Konrad Adenauer Foundation

Bakr, the analyst at Konrad Adenauer Foundation, said that most graduates know they won’t get a job in the future. “The public sector cannot absorb more employees, and there is no private sector,” he said.

Leaders of the two major parties in the Kurdish government - the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) - both met with students after the protests erupted.

On 6 December, top PUK official Bafel Jalal Talabani met with several students and vowed to support their demands, and also promised to construct a three-storey building for Said Sadiq College, PUK media reported.

The PUK also said it considers the student demands legitimate and supports peaceful protests.

Moreover, on 27 November, Kurdistan Prime Minister Masrour Barzani, from the KDP party, met students from different private universities.

"We will develop the dormitories and establish a mechanism to help the poor students," he said, Kurdistan 24 reported. "We look forward to developing the private sector in a way that people don't need government jobs anymore."

However, protesting students disavowed the meetings that fellow students had with ruling officials, a Rudaw report said.

Chiya Sharif, a member of parliament for the ruling KDP party, told MEE that the students have a right “to demand and protest for their rights in a legal and rightful manner”.

'The government is doing all its efforts to resolve all the problems of the students'

- Chiya Sharif, KDP Party MP

“When protests are conducted in a non-violent way, we stand with the students. It’s not right for any student protestors to burn political parties or government headquarters,” he said.

Sharif acknowledged that the Kurdistan region has had a financial crisis for the past few years, but said now at least there is a final decision to provide financial assistance to poor students.

“The government is doing all its efforts to resolve all the problems of the students with regards to their dormitory issues or their transportation.”

However, future protests are likely as private and public sector job markets are unable to absorb more graduates, despite attempts by Kurdish authorities to boost employment through promoting agriculture and tourism, and opening factories.

“The government does not have the capacity to fully address the demands the students have, and more students are graduating on a yearly basis,” Kurdish analyst Bakr said.

“There will be more unemployed youth with a degree, and if these people cannot get a job, they will eventually protest.”

New kind of protest

This isn’t the first time people have taken to the streets of Kurdistan in recent years.

While there were few protests during the war against IS, a year after the group’s territorial defeat in Mosul, civil servants held protests in 2018 due to unpaid wages.

Last December, thousands of teachers and civil servants protested in Sulaymaniyah over unpaid salaries.

One of the biggest protests was held in Sulaymaniyah in 2011, inspired by the Arab Spring protests.

But participants say the current student protests - and even the ones in recent years - are very different from those in 2011 which involved political parties.

Barham M Ali, 22, a philosophy and cultural studies student who is demonstrating, told MEE: “This protest was spontaneous, no one led this protest, but in 2011, the Gorran (Change movement party) and some opposition parties were involved in the protests.”

He also said that all of the protesters could speak on behalf of the movement to the media, as opposed to earlier protests in which there were designated media representatives.

For this reason, the protestors did not accept when opposition leader Shaswar Abdulwahid offered to join the protests. His party New Generation increased its seats from four in 2018 to nine seats in the last Iraqi elections.

According to Ali, these choices reflect a generation more politically aware than in the past.

“The new generation does not care about political parties, we have an experience of more than 30 years, we believe these political parties won’t change anything,” he said.

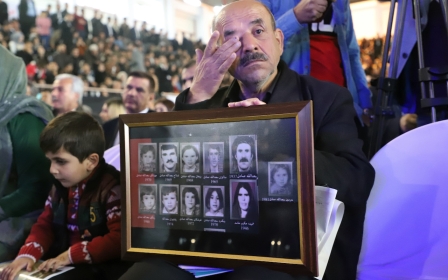

The protests also reflect a post-1991 generation which is very different from the older generation that suffered under the Baath regime of Saddam Hussein.

When the first Kurdish school was opened after the Baath regime was expelled from Kurdistan in 1991, teachers worked on the basis of Kurdish patriotism, also known in Kurdish as “Kurdayeti”, not salaries.

But these days, Kurdish civil servants want their salaries paid and there is a demand for government jobs. Further, said Ali, his generation no longer buys into patriotic slogans of the past.

“We no longer care about some nationalism terms that they used to manipulate us. As an example, during this protest, the young people and activists from Iraq and Baghdad showed support for students protesting in Kurdistan,” he said.

“We believe we are human before being Kurd or Arab.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.