In Morocco's surfing paradise, youths risk death for life in Europe

“Before coming here, I thought Taghazout was paradise," said Ilyas, an 18-year-old originally from the suburbs of Agadir, in the southern coast of Morocco.

"I thought it was a paradise for surfers, but also for young people like me who want to make a lot of money in a short time. I told myself that by working with tourists, it would be easy to get my family out of poverty and that my dreams of immigration would finally come to an end."

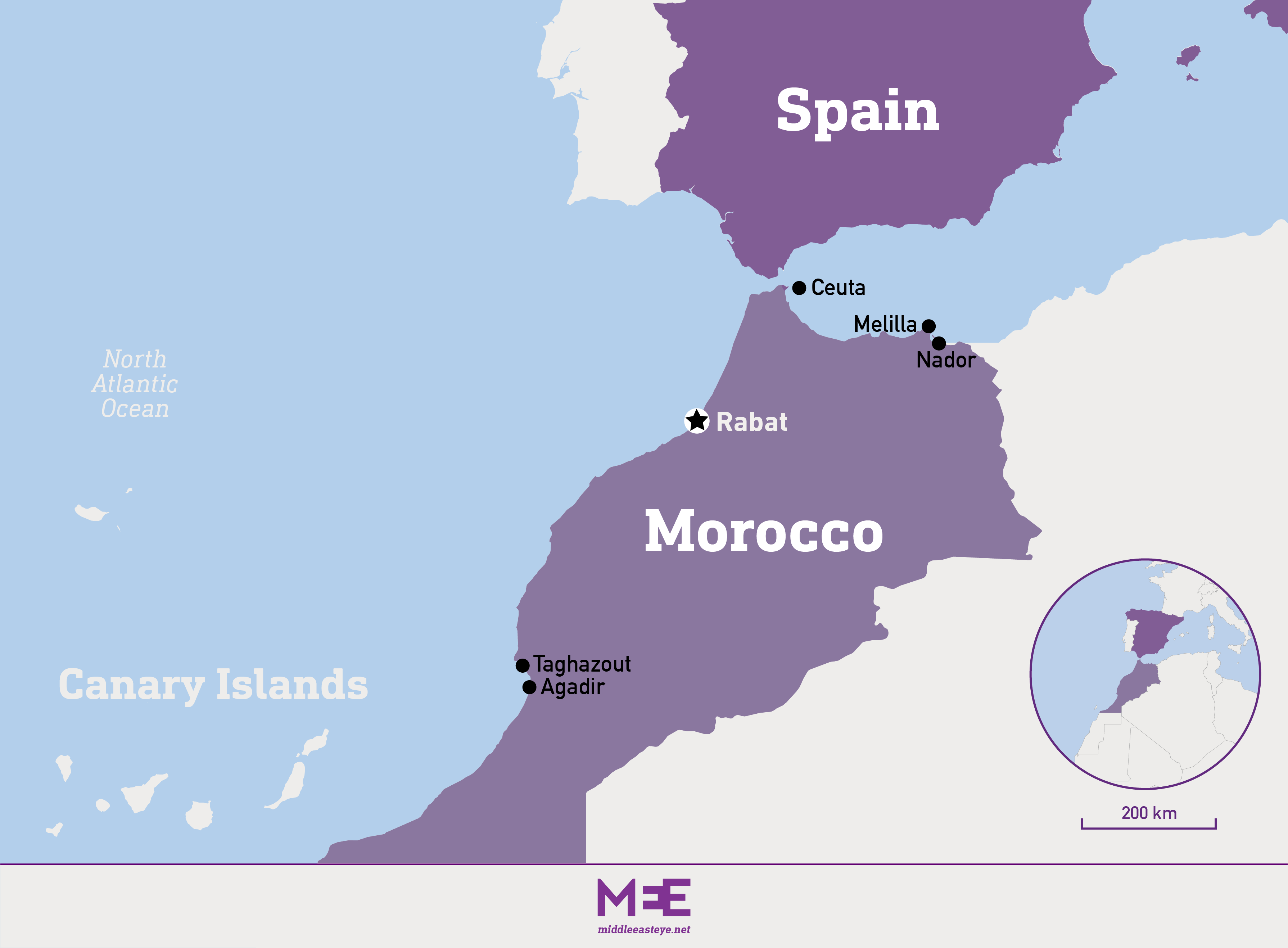

'Due to tighter controls, getting to Ceuta and Melilla isn't as easy as it used to be. You have to go south'

- Ilyas, 18

Ilyas quit school early to support his family financially. He worked as a mechanic, painter, tailor, and jet-ski instructor. "There is no job that I didn't do," he told Middle East Eye.

But over the past year, while working in the management of holiday lets, he has been preoccupied with one idea: to attempt to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

“When I was 15, I went alone to Nador [north-east Morocco] and threw myself into the Mediterranean. I wanted to swim to Melilla [the Spanish enclave in northern Morocco]. But a policeman saw me and took me back to shore.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"Due to tighter controls, getting to Ceuta [another Spanish enclave] and Melilla isn't as easy as it used to be. You have to go south.”

In his free time, he meticulously studies the different possible routes and prepares for a journey that should last three days.

Google Maps in hand, he explains that he intends to do the first part of the journey by jet-ski, before continuing at night aboard an inflatable boat.

Destination Canary Islands

As of 31 May, 8,268 migrants had managed to reach the Canary Islands from Morocco, twice as many as in 2021 in the same period.

Moreover, like Ilyas, in Morocco, more than one in five would-be migrants is under the age of 19, according to figures from the International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

“In Europe, you can achieve your dreams ten times faster than in Morocco. Here, you exhaust yourself working twelve hours a day for a derisory salary,” said Sofiane, a 17-year-old Moroccan who works in a surf shop and hasn't been paid by his boss for three months.

'In Europe, you can achieve your dreams ten times faster than in Morocco. Here, you exhaust yourself working twelve hours a day for a derisory salary'

- Sofiane, 17, surf shop worker

“The authorities have been financing the construction of luxury hotels in Taghazout for a few years while we young people remain in misery,” he told Middle East Eye.

As part of the Azur plan launched in 2001, the Moroccan authorities announced the creation of six seaside resorts across the country.

Millions of euros have been invested in the Taghazout Bay surfer village, with the aim of creating 20,000 jobs and tens of thousands of beds for holidaymakers.

The luxury hotel chains Hilton, Hyatt and Marriott have chosen to settle there.

At the same time, the Agadir urban development plan launched in 2020 seeks to revitalise Morocco's second tourist city, located some 10 kilometres from Taghazout, with the creation of infrastructures in the sectors of sports, tourism, education and health.

Faced with this economic-tourist boom, some, like Rayan, 28, have chosen to reconsider their plans for the future.

“Like many, I have also long thought that I had no future in this country. A few years ago I travelled to Greece illegally after landing in Turkey. I was able to work there for a few months, before being checked by the police and expelled,” he told MEE .

At the beginning of this year, Rayan decided to open his own hostel on the heights of Taghazout.

“Being a harraga [an illegal immigrant] doesn't interest me anymore. It's a miserable life. We live in constant fear. I'd rather try to grow my business in my country and try to immigrate later, legally this time.”

The lack of economic prospects is among the reasons most cited by those commonly called “harragas” – a term which means “burners”, of papers and borders, in the Maghreb dialects.

Despite an annual growth rate of 7.4 percent in 2021, nearly one in two Moroccans consider themselves "poor", according to a study conducted by the National Observatory for Human Development (ONDH), published last year.

Moreover, according to the International Labor Organisation (ILO), 80 percent of Moroccan workers work in informal employment, while 31.8 percent of 15-24-year-olds are unemployed.

In 2019, a study conducted by Oxfam assessed that Morocco was the most unequal country in North Africa.

Alternative migration routes

In recent years, in view of the reinforced security checks financed by the European Union, reaching Europe by land or by crossing the Mediterranean has become increasingly difficult, which has pushed would-be emigrants to find alternative routes.

Thus, more and more boats from Morocco are setting off on the waves of the Atlantic Ocean to more distant corners of the Canary Islands in order to reduce the chances of being spotted by the coastguards.

Rights groups denounce the extreme danger of these new routes, such as Caminando Fronteras, which in 2021 had identified nearly 4,400 people dead or missing on the sea routes to Spain, 90 percent of which were towards the Canary Islands.

Nevertheless, the phenomenon of “harragas 2.0” continues to develop and videos posted on the web indicate in local dialect the procedure to follow to reach Europe from different regions of Morocco, including that of Souss, where Taghazout and Agadir are located.

Sofiane said there are many starting points from the Moroccan coast. "I can name you at least three or four villages from which young Moroccans get on boats at night, in addition to those who try to hide in steamers from the port of Agadir.”

Their friends who left before them show them the way forward: “It works by word of mouth. So-and-so who knows so-and-so who knows someone who has managed to cross and who explains how to do it.

"Those who arrived in Europe seem to be happy. You see them well dressed, smiling in the photos, they make in a week the money I make in a year.”

But this apparent success often hides another facade, that of social exclusion, racism, socio-economic difficulties and the constant fear of expulsion.

In fact, as Canary Islands police chief Rafael Martinez explained at a conference on immigration in May, some migrants are deported very quickly, “in less than 72 hours”.

In addition, according to Martinez, since the thaw of diplomatic relations between Madrid and Rabat in March, suspended a year earlier, police checks have resumed with a vengeance, with a drastic drop in the number of arrivals between January – 3,194 migrants had landed on the Canary Islands – and March, where that figure had fallen to 375.

However, for Rayan, nothing will be enough to stop the aspiring migrants. “They are convinced that in Europe it is better than here. Some are not afraid to die there.

"Of course, they are wrong, because there they will face racism, language barriers, and people who will take advantage of their misery. But when I tell them that, they don't believe me,” he said.

“They want to see European misery with their own eyes, as if misery were more beautiful elsewhere.”

*This article was originally published in French.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.