Oslo accords: Why Palestinian teens invited to witness historic handshake feel betrayed

The air carried an atmosphere of joy and euphoria. Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat exchanged jokes and bursts of laughter.

As he watched on from his front row seat in the White House’s Rose Garden, it seemed to 14-year-old Iyas Ashkar, a Palestinian boy from the town of Baqa al-Gharbiyye, that he was witnessing the birth of a new Middle East.

It was a place, in the blooming optimism of the early days of Bill Clinton’s presidency, where many believed all problems could find their solution.

When the formalities were complete, the signatories of what would become known as the Oslo Accords stepped down from the platform and began shaking the hands of those in front of them.

Ashkar was clutching a brochure about his hometown which he intended to hand to Arafat.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

He figured it was a place likely to be unfamiliar to the fabled leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization, located as it was within Israel’s 1948 borders.

But as he grasped Arafat’s hand, an urgent question intruded on Ashkar’s thoughts.

“How was it,” Ashkar recalled, “that this man, wearing military garb and having led numerous wars, possessed such a softness in his hands?”

It was not the only question on Ashkar’s mind. He had been born in 1979 to a family originally from Jaffa whose refugee journey had led them to Baqa al-Gharbiyye within what was by then Israel.

They were separated from grandparents and relatives scattered across refugee camps in Jordan, the West Bank, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

However, it was the first and most innocent in a series of questions he would ask himself over the next three decades.

Over time, those questions would evolve, culminating in today's more pressing question: What exactly is the Palestinian Authority doing with the remnants of the land Israel left it in the aftermath of the Oslo Accords?

And another question follows: What was a boy his age doing there in the first place?

Seeds of Peace

In the summer of 1993, Israel's government issued a directive to local officials in some of the country’s Palestinian towns and cities to identify young teenage boys excelling in education and proficient in Hebrew and English.

After two months of interviews and workshops at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Jerusalem, four boys were selected, among them Iyas Ashkar.

These youngsters were included in an Israeli delegation alongside 16 students from the Jewish community drawn from prestigious backgrounds in Israel's military, political and social circles.

This delegation would ultimately become part of the first iteration of the “Seeds of Peace” initiative also involving teenagers from the occupied Palestinian territories and Egypt, launched in the summer of 1993 with an international camp in the idyllic US state of Maine.

The initiative aimed to cultivate a new generation hailing from conflict-ridden regions to explore avenues for peaceful coexistence and conflict resolution.

On the other side, the PLO, then based in Tunisia, coordinated with officials in Ramallah to select the Palestinian delegation.

They chose 11 students, two of whom came from the esteemed Quaker-run Ramallah Friends School.

Among them was 13-year-old Firas Hashem Ashayer.

Ashayer grew up in a family deeply engaged in the Palestinian political and religious landscape.

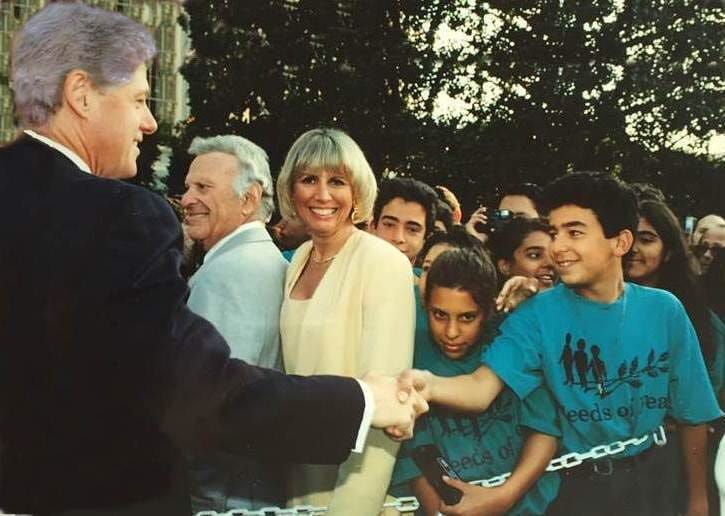

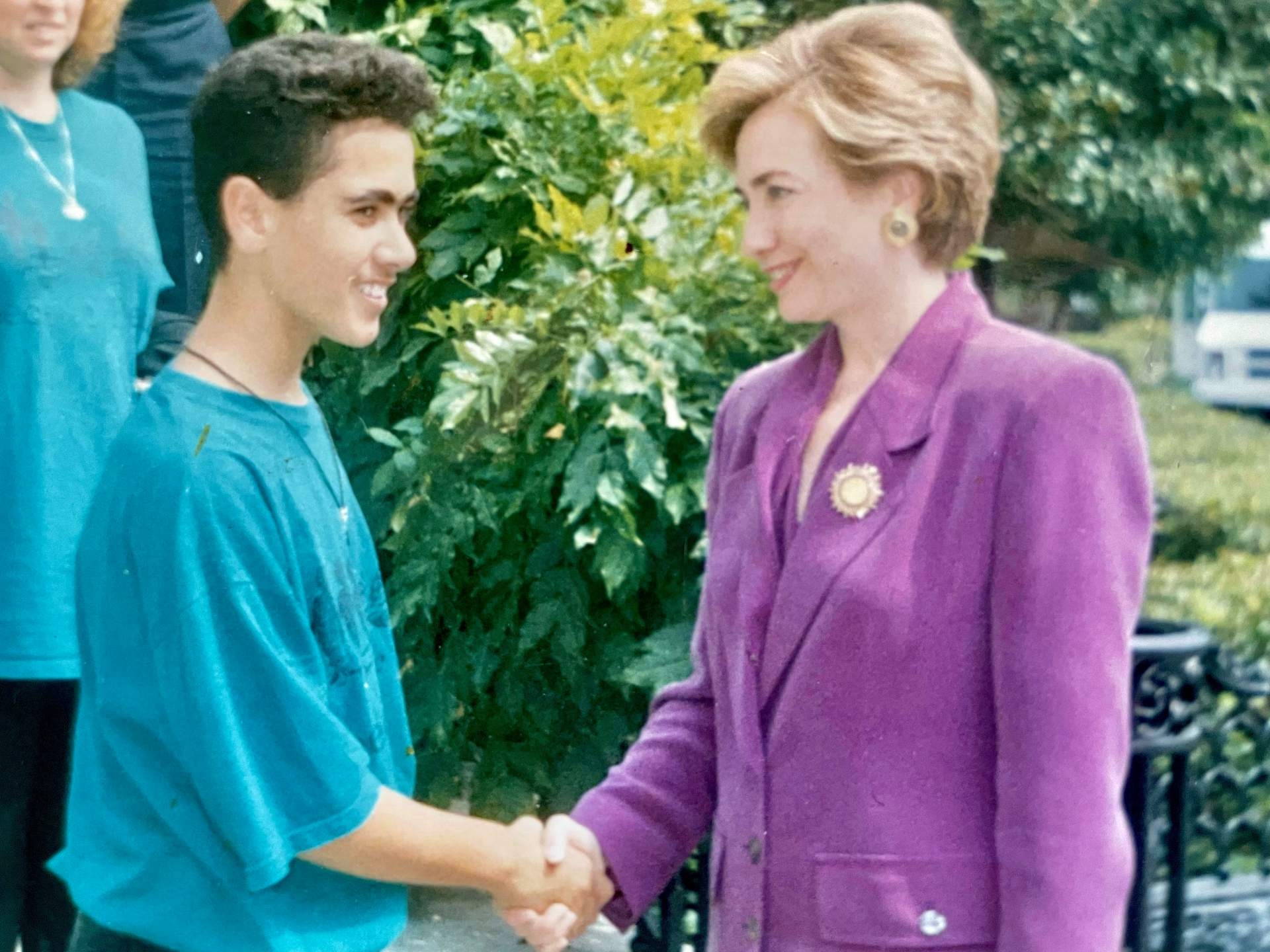

Five days before the Oslo Accords were due to be signed, Hillary Clinton, the American First Lady, encountered a Seeds of Peace delegation on a pre-arranged White House visit and invited them to attend the ceremony.

There, positioned on the front row and standing out for the cameras in their distinctive teal-coloured T-shirts, the generational symbolism they embodied was hard to miss.

To the watching world, the presence of the children signalled not only the end of one fraught chapter, but the hopeful commencement of another in which animosities between their warring peoples seemed, at last, unjustifiable.

Reflecting on his first interaction with the Israeli delegation, Ashayer told Middle East Eye: “Our imagination as children was informed solely by the environment we had been nurtured in - historical Palestine, stretching from the river to the sea.

“Dialogue proved to be futile; each side negated the other's legitimacy. Yet, we broke bread and played games, carving out a space for coexistence, albeit one that was rather peculiar.”

Regarding the pivotal moment of the signing ceremony, he reflected: “Certainly, we were only children; yet even at that age, we grasped the gravity of what was unfolding before us - although its reality was almost too surreal to believe that it was true.”

Profound sacrifices

During those protracted seconds when Arafat offered his hand to Rabin, the Israeli prime minister, Ashayer recalled that what he now describes as “a montage of Palestinians’ profound sacrifices” had flickered in his mind.

“In that instant, I found myself questioning, almost anxiously, whether the unfolding scene was in any way proportional to the magnitude of what had been endured,” he said.

Afterwards, Ashayer shook hands with Clinton, Rabin and Arafat. He recalled thinking that Arafat looked tired and weary – but Ashayer felt only euphoric to be in the presence of a man cast on that day as the representative of his people.

“We were from a background that had hitherto been largely dismissed, now standing in the very epicenter of the White House, validated by the President of the United States himself.

“Arafat's keffiyeh, for me, symbolised a seminal shift - an acknowledgment of Palestinian rights that had been systematically negated until that defining moment.”

Diplomatic theatre

As a Palestinian member of the official Israeli delegation sent to the US, Iyas Ashkar found himself subjected to a two-month preparation period.

During that time, efforts were made to convince him of his belonging to Israel, highlighting the allure of Israel's democracy and emphasising the importance of representing the remaining Palestinian community as a minority within the country.

These experiences left Ashkar grappling with unsettling emotions of discomfort and alienation.

Initially, he made an effort to sidestep the confrontations, debates and political dialogues that the initiative was designed to provoke.

However, a revelation eventually landed in his mind: he was nothing but a small part in a grander piece of diplomatic theatre.

This spectacle had commenced under Norwegian auspices and culminated with American endorsement and was supposed to unfold over a mere four-month span, beginning with Israeli troop withdrawals from Gaza and Jericho.

As the first year drew to a close, it became increasingly evident to Palestinians from all walks of life that the events constituted nothing less than a glaring diplomatic triumph for the Israelis.

This stood in stark contrast to the outcome for the Palestinians.

Arafat appeared to have affixed his signature to what many considered a lacklustre agreement with the sole objective of facilitating the PLO’s return from exile in Tunisia, irrespective of the cost.

The accords also appeared to serve the PLO's quest to reassert its dwindling authority over a Palestinian populace that had, in the view of many, sidestepped traditional leadership structures by taking the reins of its own destiny during the First Intifada.

“Israeli strategy has remained constant from the first Zionist conference in 1897 to its declaration of independence on Palestinian land, through the Oslo Accords, and even today,” said Ashkar.

“This strategy is marked by an ongoing siege on Gaza and the ceaseless settlement construction, carried out with blatant disregard for existing treaties and agreements.

“The overarching objective is maximal territorial expansion. The Oslo Accords provided Israel with its most efficient and economical blueprint for such expansion.”

For Ashkar, through the creation of the Palestinian Authority, the accords also sowed the seeds of continuing discord among Palestinian politicians, by neutralising those who resisted their strictures and rewarding those who embraced them.

“It's as if they've placed a large cake in front of them, inviting them to divvy it up amongst themselves,” he said.

Meanwhile, the accords gave Israel a route to gradually renege on other international agreements, such as the right of return of Palestinian refugees, as guaranteed by the Geneva Conventions.

In 1998, five years after the ceremony in Washington, Ashayer and other members of the Palestinian delegation were invited to again meet Arafat, this time in Ramallah.

“He informed us that he had just concluded a meeting with an American Jewish delegation, ostensibly aimed at easing tensions between him [Israeli prime minister] Netanyahu,” said Ashayer.

“Arafat told us: 'They bring me a handful of lies and tell me to be patient!'”

But, Ashayer said, when he read exuberant newspaper reports the next day of Arafat’s cordial meeting with the American delegation, a realisation dawned on him.

“I understood that Palestinian politicians, including Arafat himself, adopt a dual discourse: one to address their own populace and another tailored for the international stage. This led me to question the entire unfolding geopolitical landscape.”

'Unwavering efforts'

In the wake of the Oslo Accords, as members of the Palestinian delegation came of age, the disappointment and sense of disenfranchisement of their generation deepened.

Iyas Ashkar was no exception to this disillusionment and, like every Palestinian, he carried the weight of his homeland with him wherever he went.

Ashkar travelled to Italy to study, eventually attaining a medical degree. He settled in Brescia, a northern city that is twinned with Bethlehem.

Over 22 years, Ashkar has left an indelible Palestinian mark on Brescia’s political and cultural life, recognised by his election to the municipal council.

Soon after arriving in Brescia, he helped to establish the Italian-Palestinian Friendship Association which in turn has launched an annual Palestine festival in the city.

Ashkar inaugurated the city's first Palestinian restaurant. Serving more than just food, “Dukka” has become a venue for activities and community events that bring the Palestinian cause to life.

When the pandemic struck, Ashkar founded Cibo per Tutti - Food for All - a charitable initiative he initially funded from his own pocket and later expanded with the help of friends.

Through such civic initiatives, Ashkar continues to promote support for the Palestinian cause, advocating for boycotts against Israel and building links between the University of Brescia and al-Quds University in Abu Dis.

“Advocacy for Palestine necessitates consistent, unwavering efforts on the ground,” he said.

Ashkar bemoaned the failure of the PA through its diplomatic missions to back the activities of the Palestinian diaspora in Europe or to support boycott movements or legal action against Israel.

“The Palestinian Authority has been failing since the Oslo Accords and continues to do so to this day,” he said.

For Ashayer, the experience of the Seeds of Peace programme would also provide him with a platform to leave his homeland.

He now lives in the United Arab Emirates and holds a master’s degree in economic law from the University of the West of England in Bristol.

Faded into obsolescence

Three decades on, Ashayer believes the elusive promise of the Oslo Accords - and the prospect of the two-state solution that it feted - has faded into obsolescence.

He admits to continuing anxieties about the PA’s leadership and commitment to the cause of the people in whose name it claims to govern.

“I worry I'll wake one day to news that the PA has opted to content itself with a mere 22 percent of historic Palestine for the self-rule it covets,” he said.

But, he said, for many of those who witnessed that moment in the Rose Garden, it lives on as a formative experience that has only steeled their determination to continue fighting for their homeland.

“Palestine persists, buoyed by a generation raised in the steadfast belief in the righteousness of their cause,” he said.

“Among these youths have risen legal scholars, politicians, and media influencers, each harbouring dreams of homes in Eilat and Haifa.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.