Lost land: Nakba survivors recall rural struggle in Mandate-era Palestine

For Khadija al-Azza, her home village of Tell al-Safi was a paradise.

"We lived the best of lives,” the 88-year-old Palestinian woman told Middle East Eye, recalling the small rural community of her childhood, before its population was forcibly expelled by Zionist militias in 1948 during the Nakba - Arabic for “catastrophe”.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Between 1917 and 1948, the United Kingdom occupied Palestine during what was known as the Mandate era. Small-scale farmers, known as fellahin, were central to Palestinian society at the time, with three quarters of the population living in rural areas and agriculture the main source of livelihood, bringing families together to work in the fields.

With the Balfour Declaration of 1917, the British government vowed to establish a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine, carrying out various policies seeking to fulfill this promise - many of which came at the expense of the Palestinians.

Now, 72 years after the establishment of the state of Israel and the mass displacement of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their lands, Nakba survivors share with Middle East Eye memories of the lives and land they lost, to which they maintain a deep attachment.

Country life

At least 750,000 Palestinians were displaced from their homes during the Nakba. They and their descendants now number more than 5.4 million scattered across the occupied West Bank, the besieged Gaza Strip and surrounding countries. Many of the villages that were forcibly evacuated were destroyed or turned into national parks by Israel, trees growing on the ruins of abandoned homes.

Living for decades in crowded refugee camps in the West Bank, the elderly survivors who MEE met spoke of their steadfast yearning to return to their former homes. Some said they still have dreams at night of working in the fields.

Azza, who now lives in al-Amari camp near the city of Ramallah, recalls how Tell al-Safi used to be a self-sufficient village with an abundance of various crops - fields growing wheat, barley, corn, sesame, tomato and okra, while trees bore olives, apples, figs and almonds.

"At the edge of the village, there was a water well and, using animals, water was pumped from the well to water tanks,” she recalled. “We didn’t need anything from outside the village."

Shukria Othman, 86, shared similar memories of her village, Lifta, west of Jerusalem.

“Before the Nakba we worked hard, but we were happy,” she said. “Everything was available. We planted courgettes, cauliflowers, tomatoes, wheat, barley, lentils and corn. We had olive trees, plums and almonds.”

Just by the village stood a freshwater spring known as Ain Lifta - but according to Othman, who now lives in Qaddura refugee camp in the central West Bank, Jews residing nearby built a wall around the spring, blocking Palestinians out while they swam in the waters.

Any surplus production in the villages would be sold in the cities, allowing the village to cover its needs for other commodities.

Land grabs

Othman said the villages’ self-sufficiency was crucial for survival throughout the Mandate years - particularly during the six-month general strike in 1936, during which Palestinians protested Britain’s preferential treatment of the small but growing population of Jewish immigrants.

Jewish immigration to Palestine was a source of tensions between British authorities and Palestinians, particularly with regards to the transfer of Palestinian lands to the Jewish community - whether through unilateral handovers or by creating conditions facilitating land grabs or the purchase of lands from non-Palestinian feudal landlords.

During the Mandate years, British authorities notably enacted legislation that enabled the confiscation of Palestinian land for military purposes - lands which were then handed over to Jewish residents.

Fatima Nakhleh, 89, believes the location of her village, the since-destroyed Beit Nabala, and its fertile lands were a curse, even before the Nakba.

The Lydda Airport, later renamed after Israeli Prime Minister David Ben Gurion, was built for the British military on Beit Nabala’s flat terrain in 1936, while stone quarries were opened nearby.

“When I was six years old, Britain took our fertile land, called Wasta, and built a camp for the British army,” Nakhleh said. “When the Jews came, they established a small Jewish colony named Beni Shomar on the land between Beit Nabala and Lydda.”

Maryam Abu Latifa, who was born 1929 in Saraa, west of Jerusalem, recalled as well how her village’s lands were slowly taken over by Jewish colonies when she was a child.

"In the late 1920s, Jews built a small colony near our village and called it Hartuv. Jewish refugees from Europe began arriving, after which the kibbutz Kfar Uria was established,” she said.

United Nations Resolution 181, otherwise known as the Partition Plan, ruled to divide the land of historic Palestine, granting 55 percent of the land to Jews and 45 percent to Palestinians - despite Jews representing 32 percent of the population and Palestinians 60 percent.

Prior to the UN resolution, Jews - whether immigrants or longstanding residents of Palestine - had owned six percent of the land.

According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), Israel currently controls 85 percent of historic Palestine - whether lands where the state of Israel now stands, or through its military occupation.

Economic warfare

Under the British Mandate, land transfers also occurred alongside a deliberate targeting of Palestinian agriculture - a key link tying Palestinians to their land.

During World War I, Palestine was the site of several major battles. The impact of the war and Ottoman repression, coupled with epidemics and food shortages, left Palestinians in dire straits as they struggled to meet their basic needs.

With the arrival of the British, Palestinians found themselves having to sell their olive trees for wood to the new occupation forces in exchange for basic supplies such as bread and rice. Family heritage was traded for survival - but people’s ties to the land were crucial to getting out of the crisis.

“A few years after the war, the food and supply crises ended due to the efforts and the resilience of the farmers who had returned to their farms, cared for their livestock and planted crops and trees,” wrote the author Nabeel Alkam.

But Mandate authorities sought to transform the existing economic system in Palestine, based on traditional agriculture, into a capitalist economy.

The new economic system benefited largely from - and to - the investment of capital by new immigrants as well as the upper-class traditional Palestinian leadership that jumped on an opportunity to increase its wealth.

And so numerous fellahin abandoned agriculture in order to seek employment in cities such as Haifa and Jaffa. This work would provide a good income for their families, but make them dependent on the British.

Many Palestinians found work in kibbutzim and British “camps”, or joined security forces or the construction sector.

Meanwhile, taxes also became a heavy burden on farmers - and British authorities actively manipulated supply and demand - including by importing crops at lower prices and preventing farmers from cultivating high-income crops.

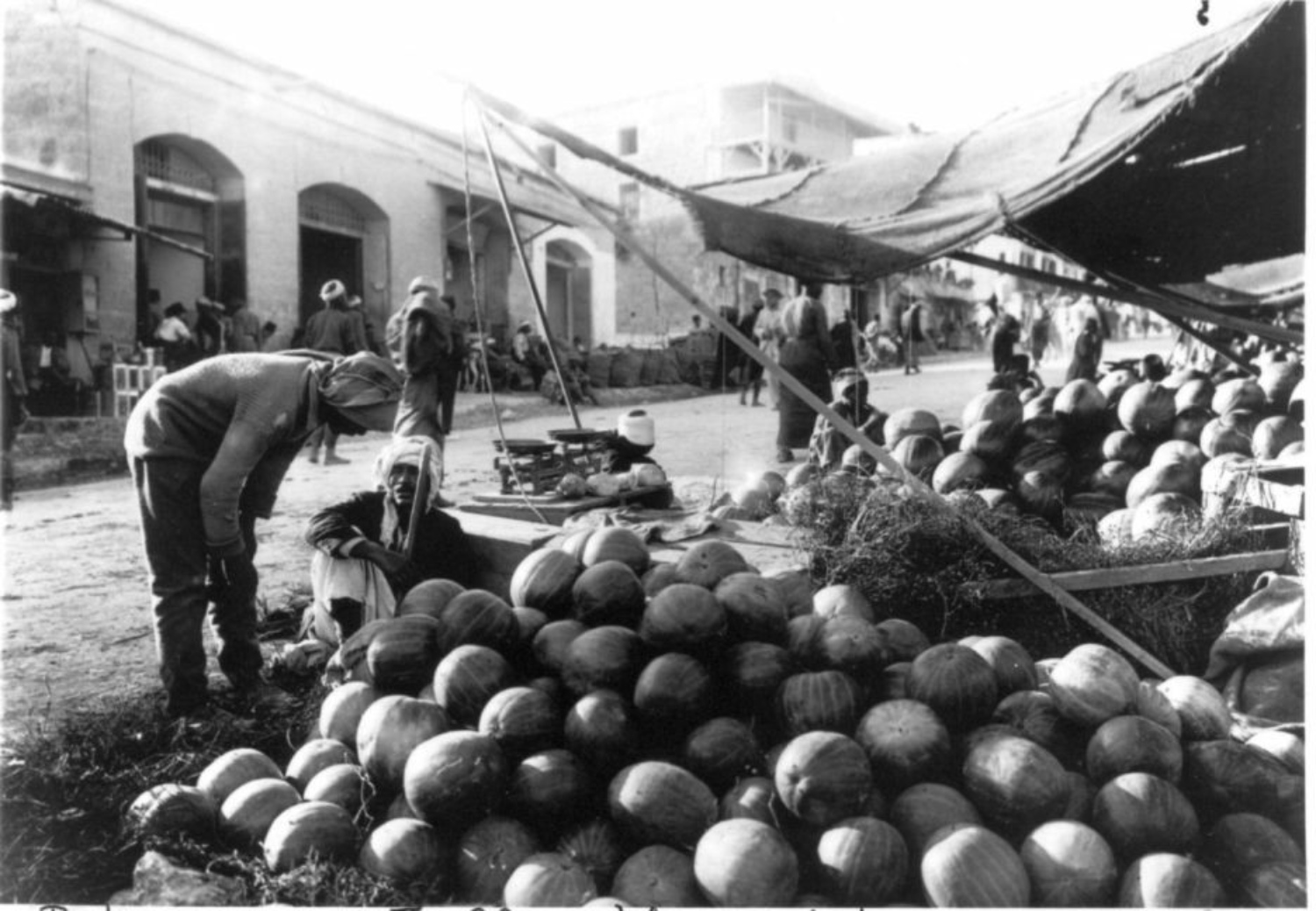

Omar Amara, 87, recalled how villagers in his hometown Miska, east of Jaffa, would produce surplus amounts of wheat - “however, we couldn’t sell it because the British imported cheaper wheat from Australia”.

Amara, who now lives in Tulkarm refugee camp, also brought up an instance when British authorities told residents of Miska that they would help export their surplus watermelons to Egypt.

“Indeed a train did arrive. The farmers loaded it with the watermelons and it departed,” he said. “For months, the peasants demanded their money for the watermelons, but the authorities kept postponing. They never paid the money, claiming the trainload had been looted.”

Armed struggle

A series of letters between British and Arab figures during World War I - known as the McMahon-Hussein correspondence - formally promised Arab independence in exchange for their participation in the fight against the Ottoman empire.

The outcome of the battle, many Palestinians believe, was decided in advance

But the Balfour Declaration and the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 dashed hopes of Arab sovereignty on their own lands, including in Palestine, where nationalist aspirations were strong.

Many Palestinians took up arms against the British colonial powers and the Jewish militias that sought to establish a Jewish state in Palestine during a revolt that lasted between 1936 and 1939.

The British general policy was to protect the Jewish population, while denying such protection to the Palestinian population, farmers in particular.

Mandate powers also supplied Jewish militias with weapons and provided them with military training, while cracking down on Palestinians for possessing any weapons.

“Palestinians only had a few old guns with very few bullets while Jews had aircraft and tanks,” Azza recalled.

Nakhleh, meanwhile, recalled an instance when Beit Nabala villagers shot their old guns towards a convoy of vehicles driving to a nearby colony.

“Then the British came and shelled our village with artillery. They killed seven young villagers, while my husband was injured,” she said.

The fact that fellahin constituted a high percentage of fighters in the 1936 revolt put them in the British crosshairs, as both economic and military measures were taken to weaken them.

For many survivors today, the British crackdown on farmers during the Mandate played a crucial role in disempowering Palestinian society as a whole and paving the way for the Nakba.

Before leaving Palestine on 15 May 1948, British forces handed over most of their weapons to Zionist militias. After decades of repression of Palestinians, the balance of power was decisively shifted, and the outcome of the battle, many Palestinians believe, was decided in advance.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.