Captagon: How amphetamines fuelled Saudi Arabia's anger against Lebanon

Hidden in pomegranate fruits originating from Syria, more than five million off-white pills were found and seized by customs in the Saudi port of Jeddah last April.

The Captagon pills, exported from Lebanon in crates of pomegranates, are an amphetamine drug extremely popular in Saudi Arabia, the biggest consumer market in the region.

'What the Gulf is doing is actually telling the Lebanese, we hold the keys to your recovery'

- Nizar Ghanem, director of research at Triangle

It wasn’t an isolated incident, as similar seizures have been skyrocketing over the past year, but it marked a tipping point for Saudi Arabia, which went on to impose a blanket ban on imports of fruit and vegetables from Lebanon to stem the trafficking of Captagon.

While this seizure paints a small part of a more complex picture of the narcotics ecosystem in the region, and the efforts by Gulf states to combat it, it also represents a key reason for the further erosion of relations between Lebanon and Saudi Arabia.

Coupled with recent diplomatic tensions that ended with the expulsion of Lebanese diplomats from Saudi Arabia and further straining of relations with Gulf states like Kuwait and Bahrain, the amphetamine trade has been affecting Lebanon's diplomatic standing. But the spat goes beyond that.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

A ‘political’ ban

Saudi's punitive measures have only been directed at Lebanon, which comes second in production of Captagon after Syria.

Caroline Rose, a researcher with Newlines Institute, believes this indicates that Saudi Arabia’s imports ban is “political” and will have little impact on stopping the narcotics from coming into the kingdom.

The pomegranates and the Captagon were Syrian, but Rose believes that amid warming relations between Syria and the Gulf countries, Lebanon has emerged as a scapegoat for the drug trade, despite the Syrian government being the main producer.

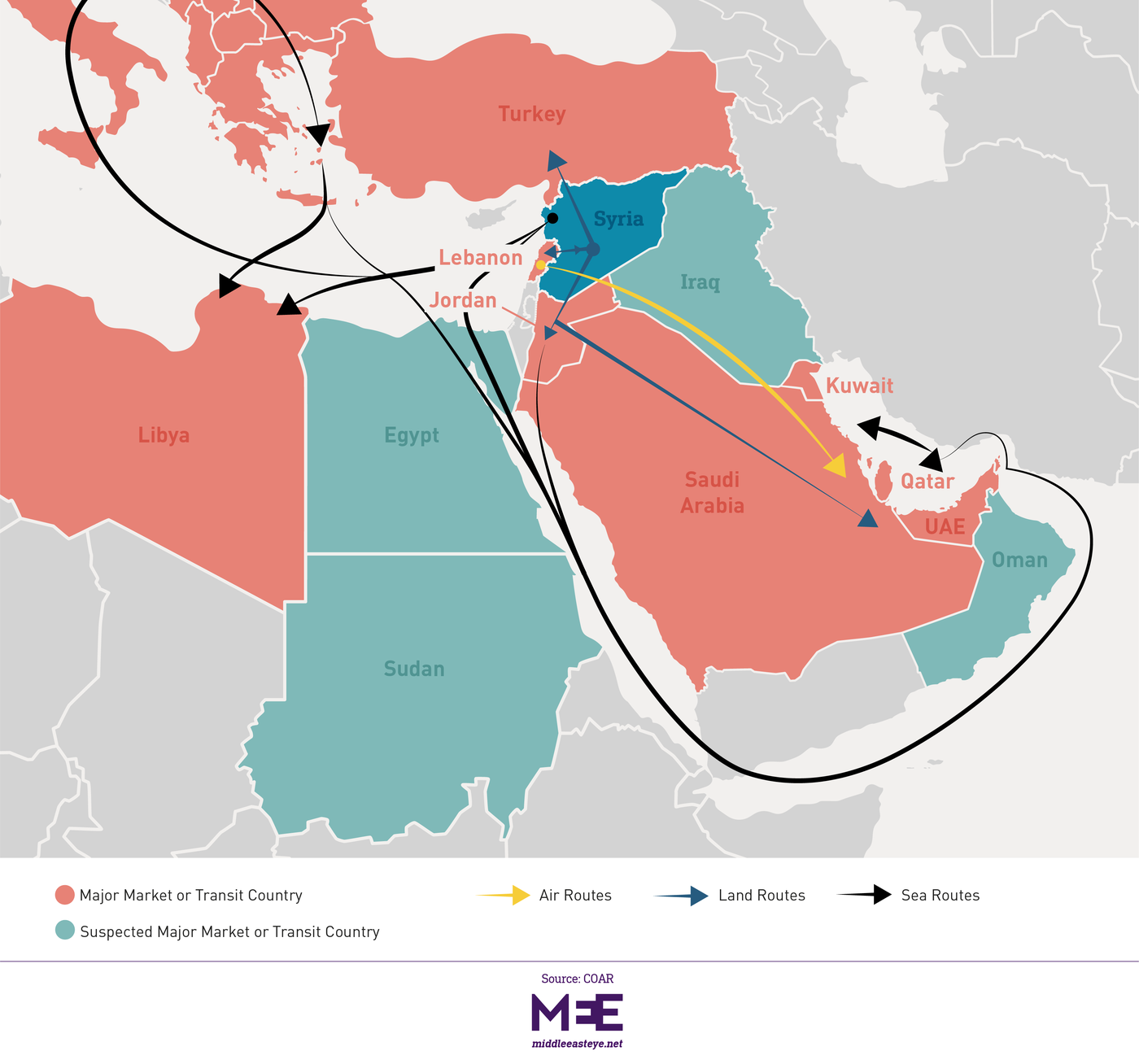

Lebanon is a facilitator and a player in a broader market, in which countries like Jordan, Iraq and some in the Mediterranean region are also involved, in addition to Syria, she explained.

Just this month, Saudi Arabia seized 2.3 million Captagon pills at al-Haditha crossing on its border with Jordan, which shows that despite the imports ban on Lebanon, alternative routes will always emerge.

The Saudi policy did not account for the highly adaptive nature of the Captagon trade, explained Ian Larson, an analyst with the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR), adding that it is likely a culmination of frustration that has grown over a number of regional issues.

“Import bans are as indiscriminate as a shotgun blast,” said Larson, “there is a clear political dimension to the latest moves, and that predates the drug issue.”

Nizar Ghanem, director of research at Lebanese think tank Triangle, agreed, telling Middle East Eye that, "the drug issue is an issue, but it's not the main one."

“The intent of the Saudis is not just to stop drugs in the Gulf, the real intention is a diplomatic one, which is pressuring Lebanon to come back to the Arab fold away from Iranian influence.”

Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan took this line himself on multiple occasions, suggesting that the import ban and the expulsion of diplomats have to do with the "continuous dominance of Hezbollah over the political system" in Lebanon.

"I think it's just that the Saudis are fed up,” said Ghanem, “they've invested billions of dollars in Lebanon and didn't get a return on investment.”

Hezbollah's role

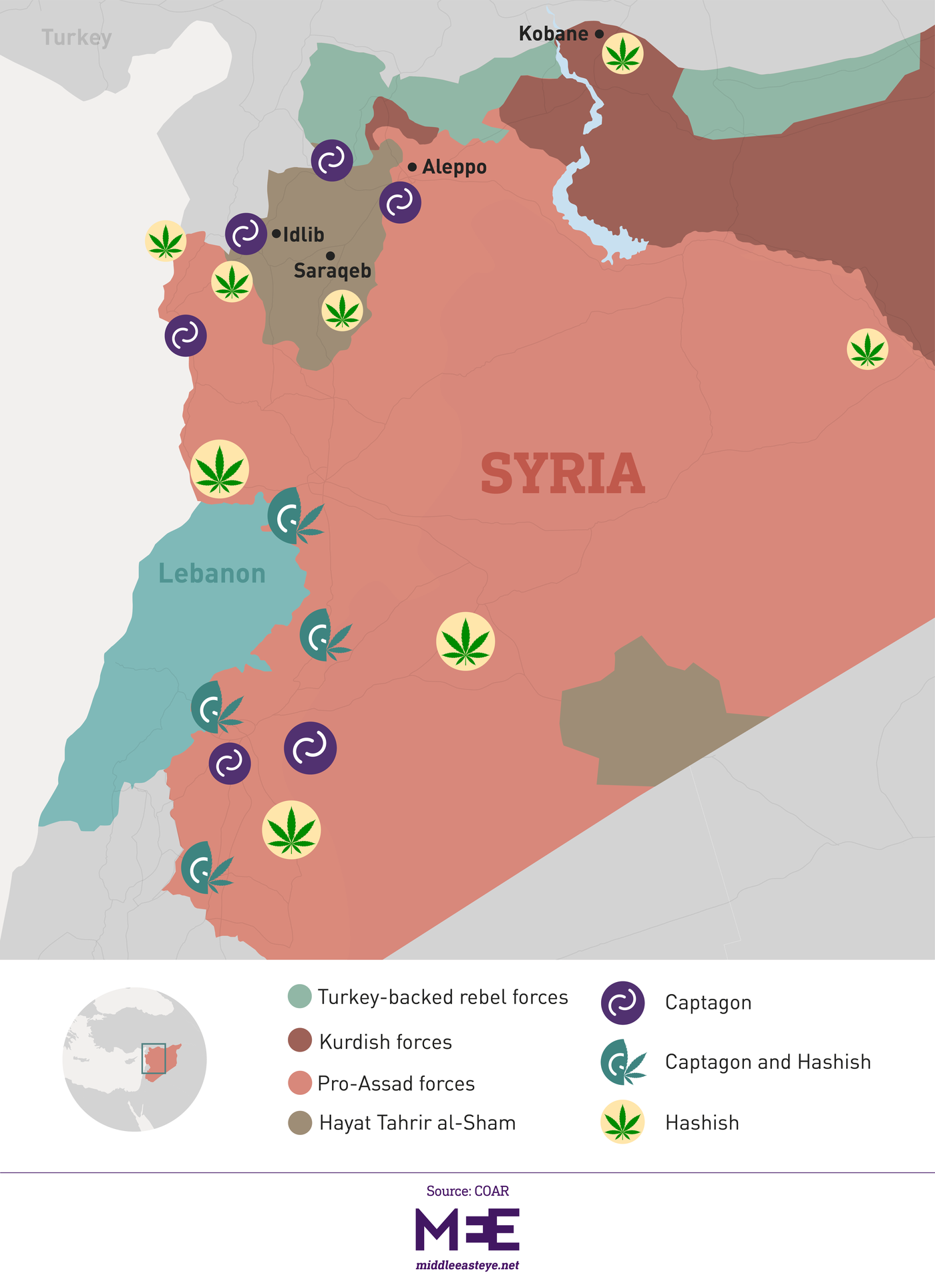

Bulgaria had long been a significant producer of Captagon, but a crackdown on labs forced the production to shift to Syria in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

“When production shifted to Syria, there was always a level of involvement from Lebanon,” Rose told MEE.

A lot of the production in the early 2000s was carried out by non-state groups, which needed mobile laboratory facilities that could be moved to avoid the Syrian state’s iron grip.

“There was a lot of evidence where Captagon labs would be shipped to Lebanon for a while, go to the Bekaa Valley and then come back into Syria,” said Rose.

An area under Hezbollah control and with a history of hashish and marijuana production, Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley was the perfect place to produce Captagon, unabated by government forces.

Smugglers in the Bekaa Valley are also no strangers to the land and sea routes that are necessary to ensure that the Captagon trade thrives.

Existing knowledge of trafficking patterns and available smuggling infrastructure in Lebanon has arguably offered Captagon producers a foundation on which they could traffick the drug throughout the region.

“Many of the networks operate in parts of the respective country which are not fully controlled by the national authorities,” Aurora Butean from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) told MEE.

But production patterns shifted and, particularly in Syria, moved from small groups operating in the dark to being condoned and facilitated by the Syrian government.

“That’s when you see a different role that Lebanon started to play,” explained Rose, who has been researching the trade since 2018.

Hezbollah has a wealth of technical knowledge and expertise, she said, which proved useful for the Syrian government as it navigated how to successfully carry on the Captagon trade as an alternative revenue source and a way to cushion the effects of international sanctions.

“The production in Lebanon is in no way comparable to the level and scale of production inside of Syria because you have the participation and the backing of the state in production,” said Rose.

“In Lebanon, Hezbollah can operate with a degree of freedom, space and independence to facilitate this trade.”

Ghanem from Triangle thinks Hezbollah has actually brought Lebanon to its current problematic position in the region.

"They are responsible for this crisis and for the drug production, but the drug issue specifically is used by the Saudis to punish Hezbollah," he said.

The opposite effect

The Saudi imports ban has eliminated the second-biggest export destination for Lebanese fruit and vegetables, making farmers who were already living in poverty - due to a crippling economic crisis - even poorer. This could push more people into the Captagon trade.

'It was pomegranates yesterday, it's going to be tumble dryers or pizza ovens tomorrow'

- Caroline Rose, researcher Newlines Institute

“There is now a competition over Captagon being used as an alternative revenue source, especially in the face of sanctions,” Rose said, “so, the worse that the economy gets, the more players are going to want to turn to Captagon production and smuggling as a source of income.”

That is why it is likely that the ban could have the opposite effect and could actually increase production and trafficking as it doesn’t tackle its real causes.

The Captagon trade has mushroomed extensively over the past year and a half, particularly in Saudi Arabia.

Between 2015 and 2019, 44 percent of Captagon seizures were made in Middle Eastern countries, 26 percent of which were in Saudi Arabia, according to data from UNODC.

The avalanche of reported seizures has put Saudi Arabia in an awkward position internationally, Rose argued.

“The seizures that you see from Saudi authorities are just the tip of the iceberg,” she said, “given the taboo with drug use and the fact that it is the largest demand and destination market in the region, they have not necessarily publicly disclosed a lot of the smaller seizures that we see every day.”

That is why confiscations are not a reliable indicator for trends in Captagon trafficking. UNODC’s Butean told MEE that countries have not reported the true extent of seizures in recent years.

“Individual countries ‘forgot’ in some years to inform UNODC of the seizures made on their territory, thus reported seizures show strong annual fluctuations in the Middle East,” she said

Butean thinks there are no indications that “such massive year-on-year fluctuations reflected changes in trafficking activities.”

But according to longer-term data collected by the UN drug agency, the underlying trend in Captagon seizures is going upwards, which is likely a reflection of an overall increase in trafficking.

“There's also a possibility that we will not see as many publicised seizures,” Rose said. “They will want the idea of this import ban to be seen as an effective measure.”

Ineffective policy

The Saudi approach to stemming Captagon trafficking lacks a public health dimension, with little being done to find out why people are using the drugs in the first place and why are Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries such a big market for it.

“More than anything, a prosocial drug treatment approach is needed,” said COAR's Larson.

Gulf states have been slow to tackle the trade through effective measures. Blanket bans on imports bear little importance if holistic approaches that focus on public health and understanding trafficking routes are not applied.

“Trafficking routes are adaptive and fluid, but so far, they haven't really needed to be,” said Larson. “Governments have been remarkably slow to devise a comprehensive approach.”

While fruit and vegetable imports from one country can stem the trafficking of Captagon through the agricultural industry, sophisticated smugglers do not put all their eggs in one basket.

“It was pomegranates yesterday, it's going to be tumble dryers or pizza ovens tomorrow,” said Rose.

That is why Saudi policies that attempt to stem Captagon trafficking seem very likely to not be about Captagon at all.

In the meantime, Lebanon is bearing the economic and political brunt of a complex ecosystem of Captagon smuggling and production. Gulf countries are continuing to warm up to the Syrian government - despite its involvement in narcotics production - which shows that the issues are about the political alignment of Lebanon, according to Ghanem.

"What the Gulf is doing is actually telling the Lebanese, we hold the keys to your recovery," said Ghanem, "we need an active diplomacy that repositions Lebanon in a way that is acceptable to the region if we're going to have economic prosperity."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.