Libya through Italian eyes: Colonialism, fascism and hidden history

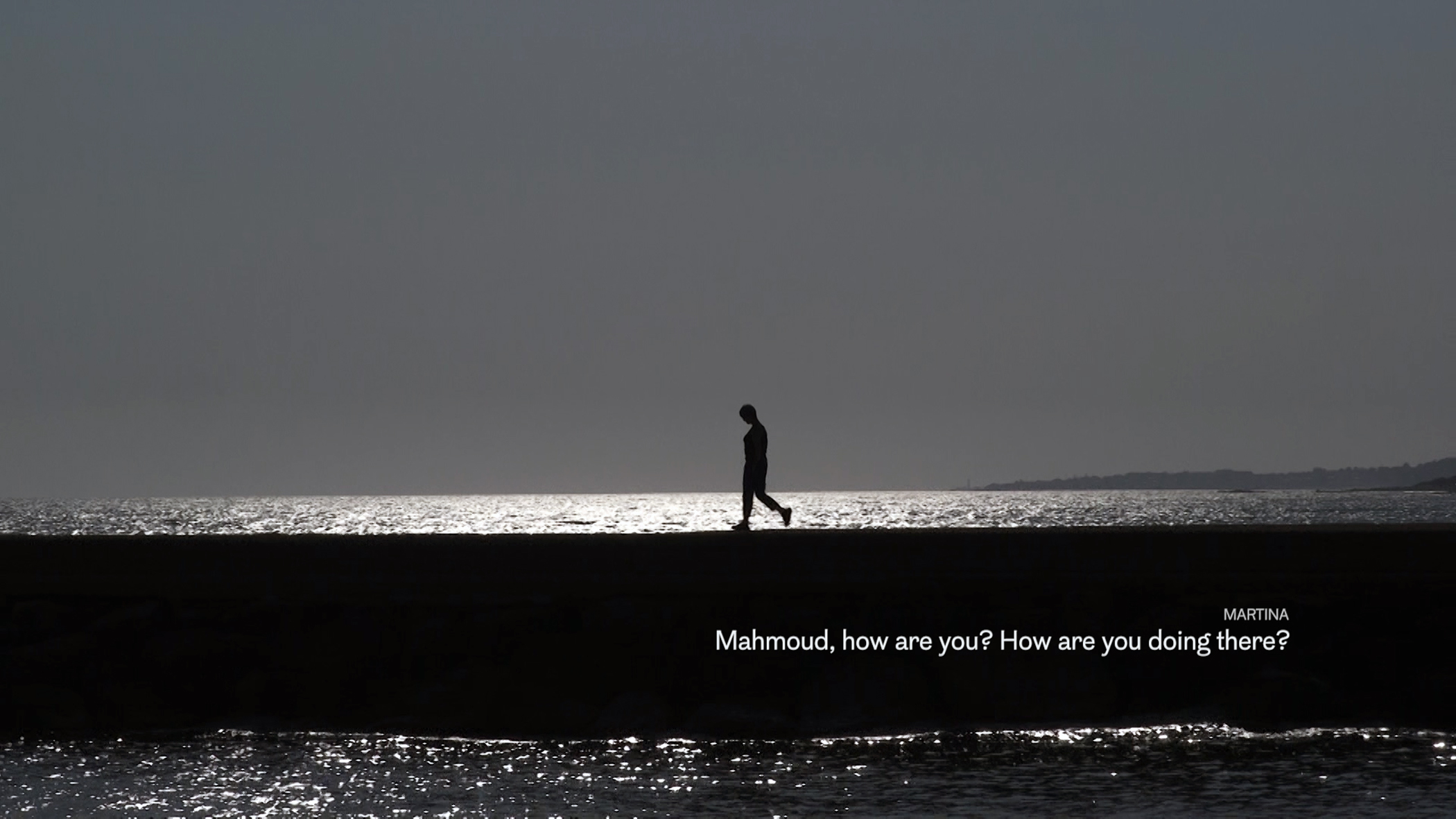

As Mahmoud's phone camera surveys streets lined with Italian rationalist interwar buildings, it appears as if he is driving through Rome. But when a mosque appears around the corner, it's clear this isn't Rome. It is Tripoli.

The video footage is part of artist Martina Melilli's documentary My Home, Libya (2018). Mahmoud, a young Libyan engineering student, is one of its main characters. We never see his face because in the documentary Melilli communicates with him via WhatsApp.

The other main characters are Melilli's grandparents. Born in the 1930s when Libya was an Italian colony, they lived in Tripoli before they were forced to leave the country in 1969, after Muammar Gaddafi’s coup d’etat. Melilli's father was born in Tripoli.

Filming her grandparent's home near Padova in Italy, Melilli identifies a map of places belonging to their past in the Italian neighbourhood of Tripoli, built during Italy's fascist era (1922-1945). She then asks Mahmoud to film these places as they look today, bringing us into a country riven by conflict and violence since 2011, and not easily accessible for Europeans.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

'I saw how the colonial past of my family was also crossing a dark period in Italian history, a time which is never discussed in the public sphere'

- Martina Melilli, filmmaker

Their relationship grows through the internet, as the two start sharing their preoccupations and their inner worlds. We quickly see how the film shortens the distance between two radically different lives.

"I love Italian people. I watch Rai 1 everyday," Mahmoud says at the beginning of the movie, referring to the leading channel of Italy's state TV broadcaster, adding "many old people speak Italian".

Later he laments the end of an era when different religions and nationalities lived side by side. "I love Tripoli. I need to see the same Tripoli it was in past, that beautiful town with mixed people, Italian, Jewish, Christian, Muslim."

'One of them'

The prime motivation for Melilli to start My Home, Libya was to understand her own identity and define an extended sense of belonging. For her, it is a much deeper concern than about being an Italian or European.

In 2010 she was in Brussels as an Erasmus student, living in the Turkish-Moroccan neighbourhood: "Every morning I used to go to get my mint tea from this man who always talked to me in Arabic," she says, perhaps thinking she was Arabic. "One day I finally told him I couldn't understand what he was saying. He answered that from 'my eyes' he could bet I was 'one of them'."

Confused by his comment, Melilli was spurred to explore her own family history to find some answers. Soon this led her to think about the bigger questions of Italy's role in Africa as a colonial power. "I saw how the colonial past of my family was also crossing a dark period in Italian history, a time which is never discussed in the public sphere."

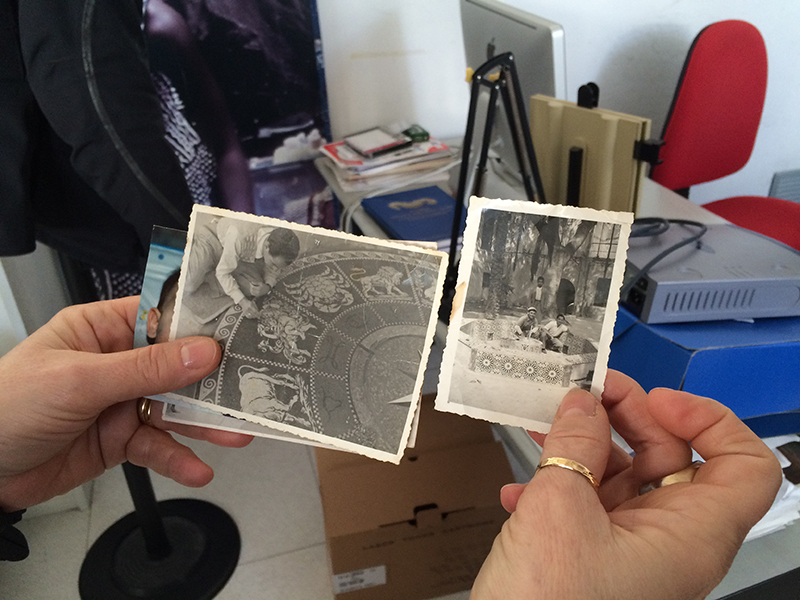

For Melilli, it all started with Tripolitalians (2010), a multimedia projects she composed from an archive of tales and documents from the former Italian community in Libya, living in Tripoli from the 1930s to the 60s. The project was followed by two short films, and finally the documentary My Home, In Libya.

Beautiful Libya

According to Melilli grandparents' recollections, Tripoli was a beautiful and international city, where Arabs and Italians lived side by side in harmony.

The Italian colonisation of Libya began in 1911-1913, a process which continued in a brutal campaign against local resistance forces through the 20s and early 30s. In these wars we see the first concentration camps, aerial bombardments and chemical weapons used against civilian populations in North Africa.

By the time her grandparents were born, this war was over. "My grandfather was born there in '36 when it was all institutionalised, so my grandparents didn't see all of this," explains Melilli. "When they were born, this wasn't discussed, and from an Italian perspective there was a pacific coexistence.

'I need to see the same Tripoli it was in past, that beautiful town with mixed people, Italian, Jewish, Christian, Muslim'

- Mahmoud, Libya My Home

"Not only the Italians, but all colonial powers were there to take advantage of the oil resources of Libya. Of course the power dynamics were clear, also in terms of the jobs and roles Italians and Libyans had in that kind of society."

Central to the film is the story of the Italian colonial experience in Libya, as it is told by Melilli's grandparents. They left soon after Gaddafi seized power in 1969, when thousands of Italians were expelled by the Libyan colonel's revolutionary regime.

"We left our heart, our friendships and everything [in Tripoli]," says Martina's grandmother in the film. "We were the only Italians in our street. In our building there was an Egyptian, above us an Arab, next to us Libyans. They were all lovely people. And when the revolution happened, they brought us food."

Although there are historians from both countries who have explored this period, such as Angelo Del Boca and Anwar Fekini (nephew of the resistance fighter Mohamed Fekini), it is an era which has yet to be fully discussed and digested by Italians and Libyans alike.

'Proud knights'

Such gaps in historical understanding have been the subject of research for Libyan journalist and filmmaker Khalifa Abo Khraisse. His grandfather was one of the fighters who resisted the Italian occupation, and was rewarded with a freedom fighter medal of honour during Gaddafi's time.

At the Libyan National Center for Archives and Historical Studies, formed in 1977 under the name the Libyan Jihad Research and Studies Center, Abo Khraisse found resources to explore this era.

One reason for this lack of a solid local historiography, Abo Khraisse said, is due to the fact that most of Libyan history was told orally.

"My father used to say almost no story was without poems, and stories without poems are often less trusted," he says. "Libyans were proud knights, and to a knight, the most important things and the source of their pride are the horses and the poetry."

Missing history

Another reason lies in the education system. Abo Khraisse says only a partial history was taught to recent generations in Libya, because of what he calls the "historical compression" by the Gaddafi government, which focused on the struggle against western colonialism.

"The discussion of contrary facts wasn't available and even forbidden. This has created a gap in knowledge between the generations, and whenever you create a gap, you also create the need to fill it."

In his analysis, this is one of the reasons that helped to shape the rise of populist movements and extremism, and groups promoting themselves as the defenders of historical honour. "Today, the discussion is dominated by those who are not interested in understanding the complexity of this history."

He is worried by the fact that those who witnessed the history of Libya before 1945 are passing away, and, without them, what happened during that time will be forgotten: "Without voices, who can speak about that era from personal experience. The only source we have is the story as the old regime told it."

Abo Khraisse is convinced that against a picture of Libya as a place of only violence and war, we should seek a different narrative, "a first-hand experience, to create an awareness that the other lives in societies like ours, to recognize them as the humans they are".

Among his works, Abo Khraisse participated in the writing of a play Libya. Back Home, a project born from the personal research of Italian actress Miriam Selima Fieno into her Libyan origins and turned into a performance by the Italian theatre company La Ballata dei Lenna. She started collaborating with Abo Khraisse after having read his articles.

Recently presented at the Romeuropa Festival in Rome, this multimedia piece tries to connect present and past Libya, balancing intimate memories, as well as encounters with three characters based in Tripoli. These are Salem - Miriam's Libyan cousin - Haidar, an Iraqi professor of English, and Abo Khraisse himself.

Selima Fieno's research was similar to Melilli's. In fact, she recreated a map, to relocate all the places described by her grandfather, who was sent to Libya during the Mussolini era and married a Libyan woman.

Abo Khraisse liked the idea and started helping the theatre company to find out more. He transferred the old names of the streets to their modern names, and created a map with it. They shared their reflections, exchanged information, videos, photos and documents.

This rich line of communication that they managed to establish allowed them to compare the current situation of Libya against its past and to highlight the relationship between Libya and Italy.

Whose history?

While Abo Khraisse's research as a filmmaker and writer blends Libyan local history and modern chronicles with personal memories, Melilli's documentary was almost exclusively personal. Because of this, her film has been criticised by some for not tackling the hard questions of history.

Melilli says she started out with a view that condemns colonialism and its crimes, yet found in talking to her Libyan opposite that his perception of this history was different.

"Both in talking with my grandparents and Mahmoud, I put on the table my values. I talked with people who lived a specific experience in time, which is definitely not all-encompassing, nor is it the only one. But it's the one they have."

In the beginning of the movie she tells Mahmoud about the harm that the Italians have done in Libya: "But in the moment Mahmoud's version is a different one from mine, what rights do I have to push in a direction that I have myself decided? It won't be ethical on a professional level. I can't impose my original idea only because it is more ethically correct in regards to the facts I intended to tell."

Colonial crimes

Another Italian artist to tackle the subject of his country's colonialism in Libya is 43-year-old Florence-based Leone Contini, in his 2017 multimedia art-meets-anthropology exhibition, "Bel Suol d'Amore – The Scattered Colonial Body"

While he also begins with personal histories, Contini's approach was different from Melilli's, as he insists on the agency of the artist in taking colonial responsibilities on his shoulders. He believes that the cultural practitioner should "deconstruct from the inside" the dynamic that brought racism and colonialism to Libya.

Contini's "Bel Suol d’Amore" mostly focused on Rome's museum collections and archives, as well as the memories of the artist's own grandmother, born in Tripoli.

"My great-grandparents arrived in Libya in 1931, at the very violent time of the insurgency in Cyrenaica," says Contini. "The 30s were the peak of fascist violence, followed by the war and the pogrom - which my grandfather also saw."

In 1930, the Italians forced 100,000 men, women and children from Cyrenaica into concentration camps. Over the next three years, 60-70,000 of the prisoners are believed to have died, more than half the population.

After the war, a pogrom targeted the Jewish community of Tripoli, killing more than 140 Jews.

Inevitably, the stories of his grandmother, born in 1914, are very different from those of Melilli's grandmother, born two decades later. “[Her] stories were full of violence, perpetrated by the fascists, as well as regarding the general environment of Libya."

Contini's grandmother was a witness to the events that followed the so-called "pacification" of Tripolitania in 1931-1932 by Mussolini's top military officer in Libya, Rodolfo Graziani, known as the "Butcher of Fezzan" for his actions in Cyrenaica.

Contini's grandmother hated Graziani, he says. "She was a woman, and she came from a socialist family. She had a different sensitivity from many other Italians I have talked with in my research," says Contini. "Perhaps they didn't see or register many things – details like beheaded Arabs brought as a trophy on a jeep by Graziani's 'butcher' Piscopello."

The main aim of Contini’s research was to shed light on this dark period of Italian history. "Many believe that colonialism is only a consequence of fascism," notes Contini. "This is not true because we know that Italian colonialism started before fascism and somehow outlived it."

Contini thinks that the most disturbing part of his grandmother's history is precisely this colonialist legacy, deeply rooted in the European mindset.

"In the post-war period the Italians were not the owners of Libya anymore, but they still kept a sort of apartheid in place," he says. "We have a gap in historiography from '42 and '67, as most Italian historians stop researching Libya when Italy stopped having its colonies."

According to Contini's grandmother, at the end of this interregnum, when Gaddafi seized power, Italians couldn't foresee they were about to be kicked out of the country: "It wasn't so hard to see, but when it finally happened, everybody was so shocked. You heard them saying: 'How that could happen? We were so kind with the Arabs'."

Dark materials

Looking into the museum archives, Contini found himself handling very disturbing material - such as face masks of Libyans, created by a fascist anthropologist. He had to figure out if it was sensitive way to exhibit it.

Without a roadmap traced by other cultural figures about this time in history, he worried he would be perpetuating a colonial, orientalist and ultimately racist approach. This was something he wholeheartedly wanted to avoid.

"I always emphasise that my work goes under 'Italian studies'," says Contini. "I don't feel entitled to talk about colonialism; I didn't want to be a white person talking about 'the other'. The only thing I could do was to reveal the harm we did, and how this is still part of us. I feel I'm not entitled to touch some materials that are inside the museum - only a Libyan artist can."

In his putting side to side a picture of his grandmother and a bust of Graziani ("She would have killed me for that!"), Contini created a semantic and emotional short-circuit. Putting the intimate dimension next to public atrocities, he allowed viewers to access two parallel narratives and judge for themselves.

"With my research I was looking for a catharsis, but I stumbled into even more unresolved questions," says Contini. "I feel for Italian culture in general, there is still a lot to excavate before we get to a point when we can let this go."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.