Let's play: Learning Arabic, one Lego brick at a time

In a quiet corner of a Cairo suburb, Ghada Wali crouches down on the ceramic tiled floor of her family home, creating patterns with Lego blocks. The 30-year old hasn’t raided her old toy box in a fit of nostalgia. Rather, she’s putting the finishing touches on her award-winning graphic design learning method.

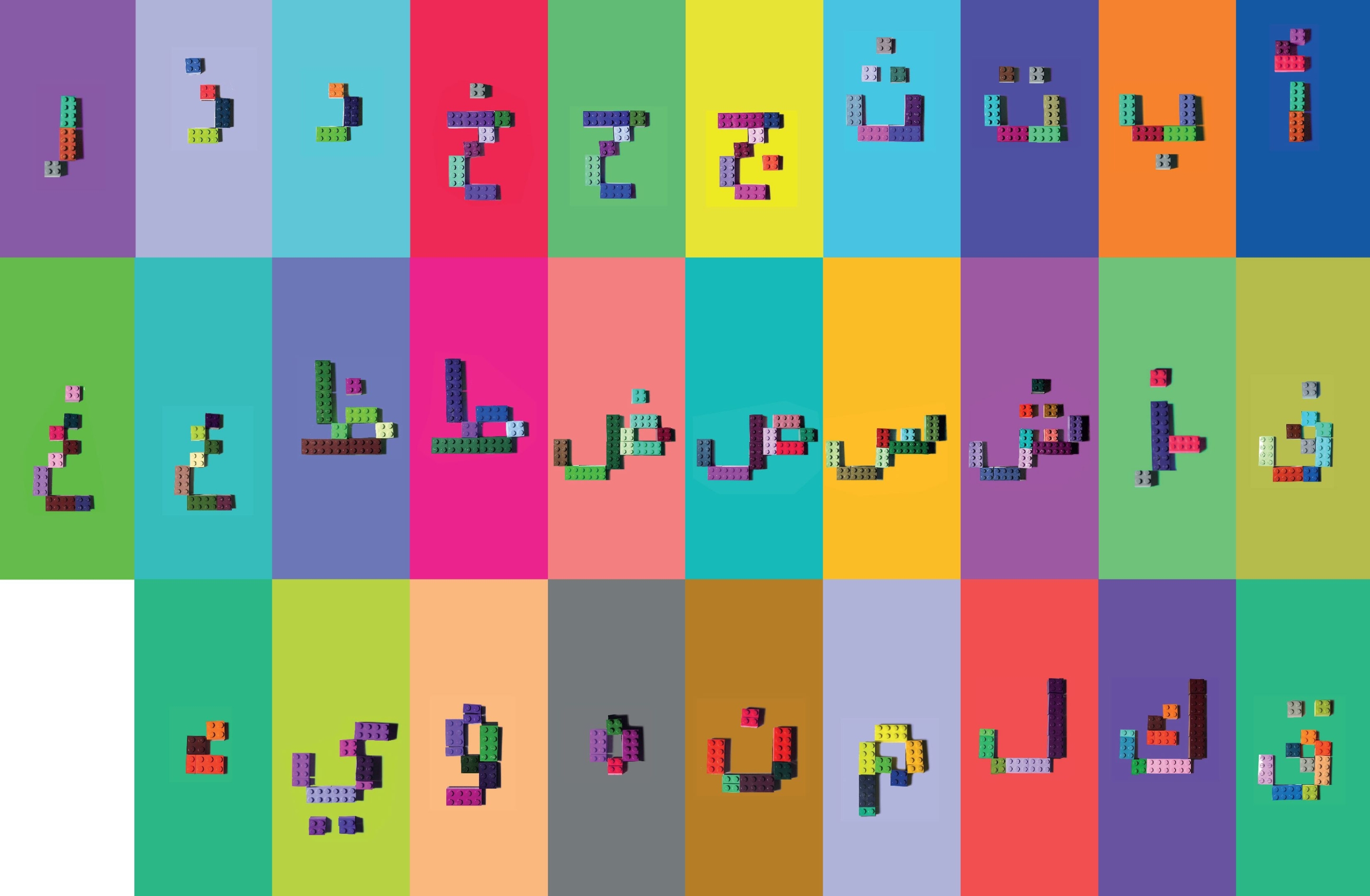

Wali, a graphic designer by trade, has come up with a visually bold and engaging way of introducing the written Arabic form. Using Lego blocks as inspiration, she created a design concept presenting each letter of the alphabet, to introduce the Arabic language not just to children but to all "young learners, [and] foreign speakers".

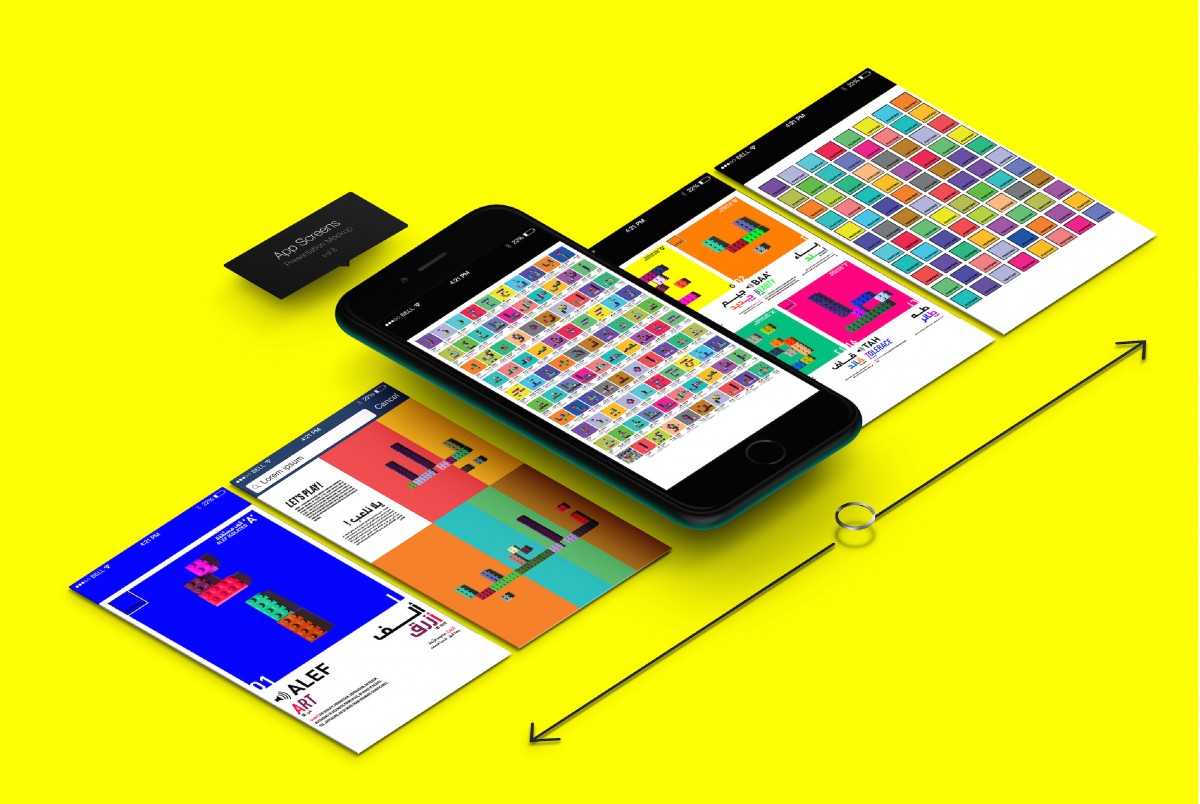

The images were then printed in a booklet to be sold as part of educational kits under her own brand, Let’s Play, each of which includes a pack of Lego for children and learners to create their own words.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Let's Play made the prestigious Society of Typographic Arts list of best 100 graphic design pieces in the world in 2016, and in the following year Wali became the first Egyptian woman to make the Forbes 30 under 30 list.

In 2017, she gave a TED Talk in Arusha, Tanzania, and in the same year spoke at the World Youth Forum in Sharm el-Sheikh. The following year she took her mission to UNESCO on World Arabic Language day.

The achievement, she says, is just a step towards a much bigger personal goal of sharing her love for Arabic with anyone wanting to learn.

"I want to introduce the Arabic langague to young learners, foreign speakers, and to help refugees integrate into their host societies, but also to the youth within the MENA region and living abroad," says Wali, who has been working with the UAE’s Ministry of Education to add Let’s Play to the early years school curriculum.

"The beauty of Arabic is its richness, the fact that you can express one emotion with all its layers," she says.

Piecing the puzzle

Wali is used to commercial design success. Professionally, she has worked on big budget advertising campaigns, among them a Pepsi one featuring footballer Mohamed Saleh, and Egyptian jewellery designer Azza Fahmy's latest collection.

She has also created other forms of typography, including developing the Hierolatin Typeface, which merges hieroglyphics and Pharaonic iconography with Latin typography. But designing language as a learning tool, came unexpectedly.

The middle of three sisters, Wali was studying for a master's degree in Design at The Florence Institute of Design in Italy, when she realised how much she missed her native Arabic.

In Egypt and the UAE, where she had grown up, she was used to speaking Arabic and seeing the Arabic text on billboards, road signs and building names, and she longed to be surrounded by the familiar text.

'When I saw the Lego, I had a light-bulb moment'

- Ghada Wali, graphic designer

Hoping to find comfort in the Arabic script, she went to the main library in Florence to find books by Egyptian author Naguib Mahfouz (whose book covers she redesigned to mark the 10th anniversary of his death) or Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani.

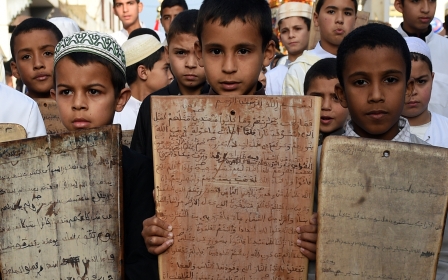

But all she found were books about terrorism under the Arabic and Middle Eastern section.

"I thought, how can I stop the world from seeing us as evil, as terrorists of this planet, and start perceiving us as equals, fellow humans?" Wali says in her TED Talk. "How can I... honour the Arabic script and share it with other people, other cultures?"

At the time, Wali was sharing a flat in Florence with her younger sister who had been sent a large box of Lego for a multimedia work project. "When I saw the Lego, I had a light-bulb moment, and the idea behind 'Let's Play' was born."

Then the pieces of the puzzle started coming together.

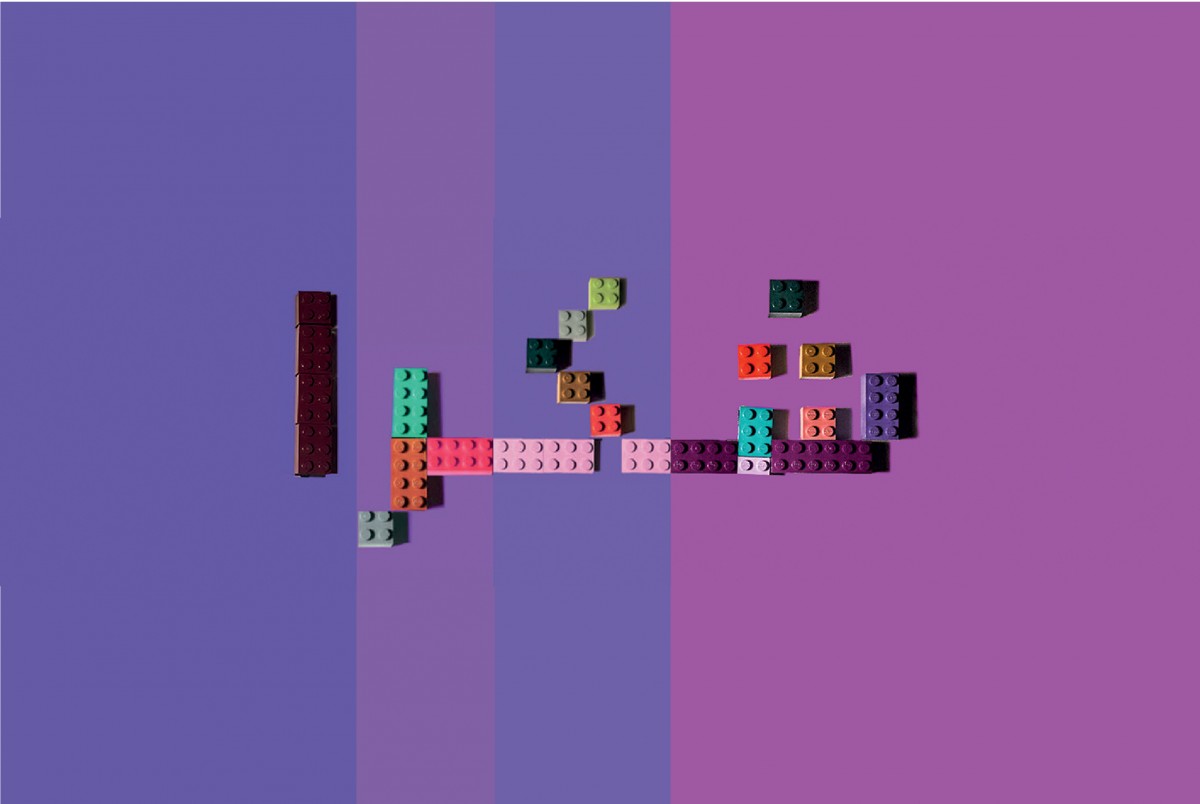

Wali spent a week painstakingly creating her concept. She colour-coded each Arabic letter then built all 29 letters using the Lego pieces and photographed each one separately. On a computer programme, she then chose complementary coloured backgrounds and typefaces.

Each letter was recreated in four different forms, as most Arabic letters change shape according to where they appear in a word: at the beginning, in the middle or at the end. In total she designed 116 letters. Her self-funded educational kit, which is due out in early 2021, includes a booklet that explains how each letter is pronounced and how the letters change their form, as well as a 400-word dictionary.

Wali hopes users can then play with the Lego pieces and recreate the Arabic letters, building words and learning through play. In addition to a new mobile app she has since developed to complement the tool, Wali is currently developing a braille version too.

The business of play

Wali is not the only one introducing the different Arabic letter forms to new learners.

Hala Gharib, a mother of two and owner of online toy company Alaabi (meaning "My Toys" in Arabic), had been concerned about the lack of quality educational products in Arabic even before she started her family. She noticed that “learning tools in Arabic seemed dated compared to other languages” and decided to design her own. Her first toy was an Arabic sound board “using colourful and chunky alphabet letters”.

Not long after, she added Arabicubes, a bestselling product created by another pioneer in language through play, Hanna Lenda, that is still in high demand.

“It’s our role to make it simple and easy for kids to learn,” Gharib says. “And visual memory is a huge part in learning a language.”

The 48 wooden cubes feature a stand-alone letter on one side, and by rotating the block forwards or backwards the letter appears in its different forms, creating simple words and phrases when joined.

'Learning through play is crucial, particularly in the early years, and even for adults'

- Dr Saussan Khalil, Arabic educator

Gharib says there is room on the market for different types of tools to get people learning Arabic using a sensory approach. But the issue isn’t the ideas, it’s the funding. Philanthropists, the business community, need to realise the importance of investing in education that is engaging.

Like Wali, Gharib says it's not just children that her products are designed for. The Arabicubes have been popular with adult learners, speech therapists and social workers in Syrian refugee camps in Greece.

Saussan Khalil, director of Kalamna, (meaning "Our Words" in Arabic) a programme teaching spoken Arabic through phonics to adults and children alike, welcomes all ways to teach Arabic through play.

Khalil, also a senior Arabic language teacher at the University of Cambridge says: “Certainly learning through play is crucial, particularly in the early years, and even for adults. At Cambridge University we have the world’s first Lego Professor of Play, so this shows not only the importance of learning through play, but the application of Lego in many different ways to enhance the learning process.

"It is also well established that Lego play is used to help children with autism develop their social skills and there are professionals trained to do just this, such as those at Bricks for Autism."

She encourages the use of simple educational toys in her children’s Arabic classes, and uses the Arabicubes as well as play dough for younger children to learn to form the shapes of the Arabic letters.

Arabic Alphabet Snap is another playful way to help learners practice recognising letters in different positions (initial, medial, final), and connecting letters to form words, a bit like the Arabicubes.

Games such as Hareef el Harouf (meaning "The Letters Expert", in Arabic) from Makouk a company specialising in educational Arabic toys, is also popular with children, Khalil says.

The importance of learning through play has been studied over the past century, with Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget noting how play significantly encourages cognitive and language development.

And although Wali has promoted her work as a way to make Arabic learning more approachable through playing, the message is deeper still.

Her hope, she says in her TED Talk, is to break “the fear of language and barriers between people, cultures, [and] countries”.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.