Teaching Arabic to kids: How families are putting the fun back into reading

Reading to children should not be a chore. But the pleasure a child gets from a book is lost if they do not understand the language.

It’s a problem faced by parents worldwide, not least in Arabic, where children’s books are written in a formal standard so distinct from their spoken tongue. But a handful of pioneers are now making headway.

Riham Shendy, 45, started translating popular English-language storybooks into Egyptian Arabic after she had her twins, Ali and Leila, in 2013. An economist by profession and with a PhD in Applied Economics, she was working at the World Bank in Washington DC when she and her German husband, Steffen Reichold, decided to teach their son and daughter their respective mother tongues.

Some popular children’s books have been translated into classical Arabic, like Julia Donaldson’s The Gruffalo and The Very Hungry Caterpillar, by Eric Carle. But it is rare to find them in a’amiya, the commonly spoken dialects of the language: even the names of the foods that Carle’s caterpillar munches his way through do not correspond to the vocabulary that parents teach their children.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Instead, the collection of Arabic children’s books that Shendy had proudly amassed were in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) or Fusha, a formal version mostly used in official communication, documentation and literature.

The language spoken across the Middle East and North Africa is a dialect of this form, unique to each country. Regional variations in vocabulary and grammar mean it is sometimes incomprehensible across borders.

There is no quicker way to suck all the fun out of reading than simultaneously translating each story page from formal Arabic into colloquial Arabic

At first, says Shendy, reading to her children was straightforward: “At the beginning you open a book, it’s just an apple here, a banana there. Fine.”

But once the twins were around 18 months old, life became trickier. There is no quicker way to suck all the fun out of reading than simultaneously translating each story page from formal Arabic into colloquial Arabic.

“I am fluent in classical Arabic, I was brought up in Egypt,” Shendy says. “The minute you have something in Fusha rhyme and you’re translating word for word, you’re changing the structure of the sentence, you’re changing the words, you lose the rhyme."

This, she says, is why the Dr Seuss books are so helpful for children – because they help them understand the sound structure of language.

“Sometimes I’d forget to say something and they’re like: ‘But you didn’t say that he was sad’... Oh yeah, well it’s because I made that up when I was translating last time.”

To avoid being caught out again, Shendy translated some of her children’s favourite stories into colloquial Egyptian, painstakingly preserving the rhythm and rhyme. She then printed out her translations and glued them over the English in the book.

Five or six books later, in November 2016, Shendy posted her translations on a website, which she called Tuta Tuta, after an Egyptian phrase traditionally used to end a story. As the website’s popularity grew, so she started to play around with the format, posting videos of her reading the stories, as well as offering downloadable audio files.

But the process was becoming tiresome. Shendy tried to make contact with publishers to see if they would consider printing books in Arabic dialects.

“I was running out of books,” she recalls. “I can't create a book every time I want to read the book. I wrote to Macmillan, I wrote to Ladybird. Nobody answered me. Of course - I’m no one.”

The unspoken struggle

Shendy decided that there was only one thing for her to do: go it alone. A self-professed nerd, and thanks to her academic background, she spent 10 months collating research to support her proposal. The result was the academic paper The Limitations of Reading to Young Children in Literary Arabic.

“Ample research has shown that the benefits of reading aloud to young children extend far beyond developing their literacy skills,” Shendy wrote, referring to “speakers within a single community (nation) [who] simultaneously use two varieties of Arabic... Reading to children has a rich role in enhancing their emotional, social, and cognitive development.”

Although her paper was then published by an academic journal, it didn’t move her any further forward. In March 2019, she pitched a storybook to Egyptian publishers. But they were not interested in publishing something that they wouldn’t be able to market to the rest of the region.

Marcia Lynx Qualey, a translator of Arabic children’s literature and co-founder of the World Kid Lit project, says that children's publishers are in a difficult position.

'Arab children are asked to surmount obstacles that no other children in the world are asked to do'

- Niloofar Haeri, linguistic anthropologist

“They may want to publish books in a’amiya, but they also want to sell into as large a market as possible. This means being able to sell across borders, particularly into wealthier Gulf countries, but it also means selling to schools and libraries. Generally, it's only the books entirely in Fusha that are seen as ‘properly’ educational.”

In this respect, Arab readers have it tough: they need to learn both forms of the language and switch between the two - even if they haven’t yet learnt to read or write by themselves.

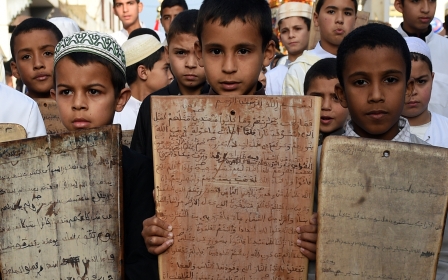

Niloofar Haeri, a linguistic anthropologist at John Hopkins University, wrote in 2003 in Sacred Language, Ordinary People, that "Arab children are asked to surmount obstacles that no other children in the world are asked to do - namely, learn their subjects while lacking proficiency in the language in which those subjects are written."

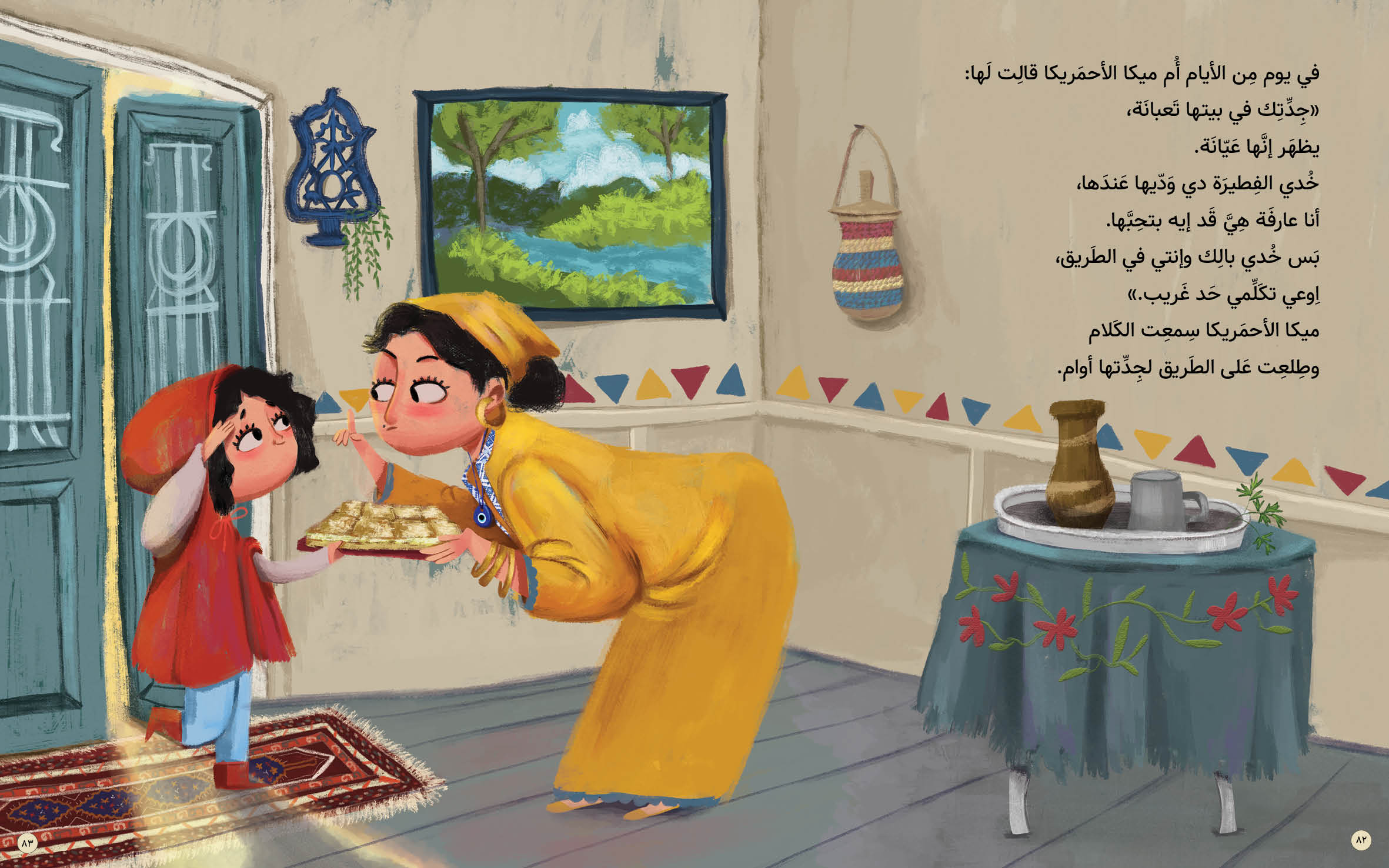

In April, Shendy self-published Kan Yama Kan (Once Upon A Time), an anthology of eight popular children’s stories, all in her translation. Tales like Mika al-Ahmarika and the Wolf (Little Red Riding Hood) are not only retold in Egyptian dialect but also given the cultural dressing that helps teach children about their heritage.

In Shendy’s version, Mika (Red Riding Hood) carries a fiteer (an Egyptian crepe) instead of a pie, to her poorly grandmother, who lives in the oasis city of Fayoum near Egypt’s only waterfall in Wadi al-Rayyan.

Shendy included fun facts to generate talking points with young children, as well as introduce concepts like the environment.

While wolves aren’t common to Egypt, she set the tale in Fayoum after she discovered that one had been found and released there in 2018 by the Ministry of Environment.

Likewise, her version of The Ugly Duckling is set in the Upper Egyptian city of Sohag, where the duck hides among the sugar cane plantations; the women in the Magic Belila Pot wear Bedouin clothing and put belila wheat cereal in the pot instead of porridge; and in her version of The Three Little Pigs, based in the western desert, the wolf falls into a huge bowl of green molokhia, a jute leaf stew.

“I didn’t start off knowing that I’m going to do different governorates but I needed to add a depth,” Shendy says. “So you’re not just listening again to Little Red Riding Hood, you’re going to listen to her now in Fayoum with her mum looking like a typical Fayoum mum.”

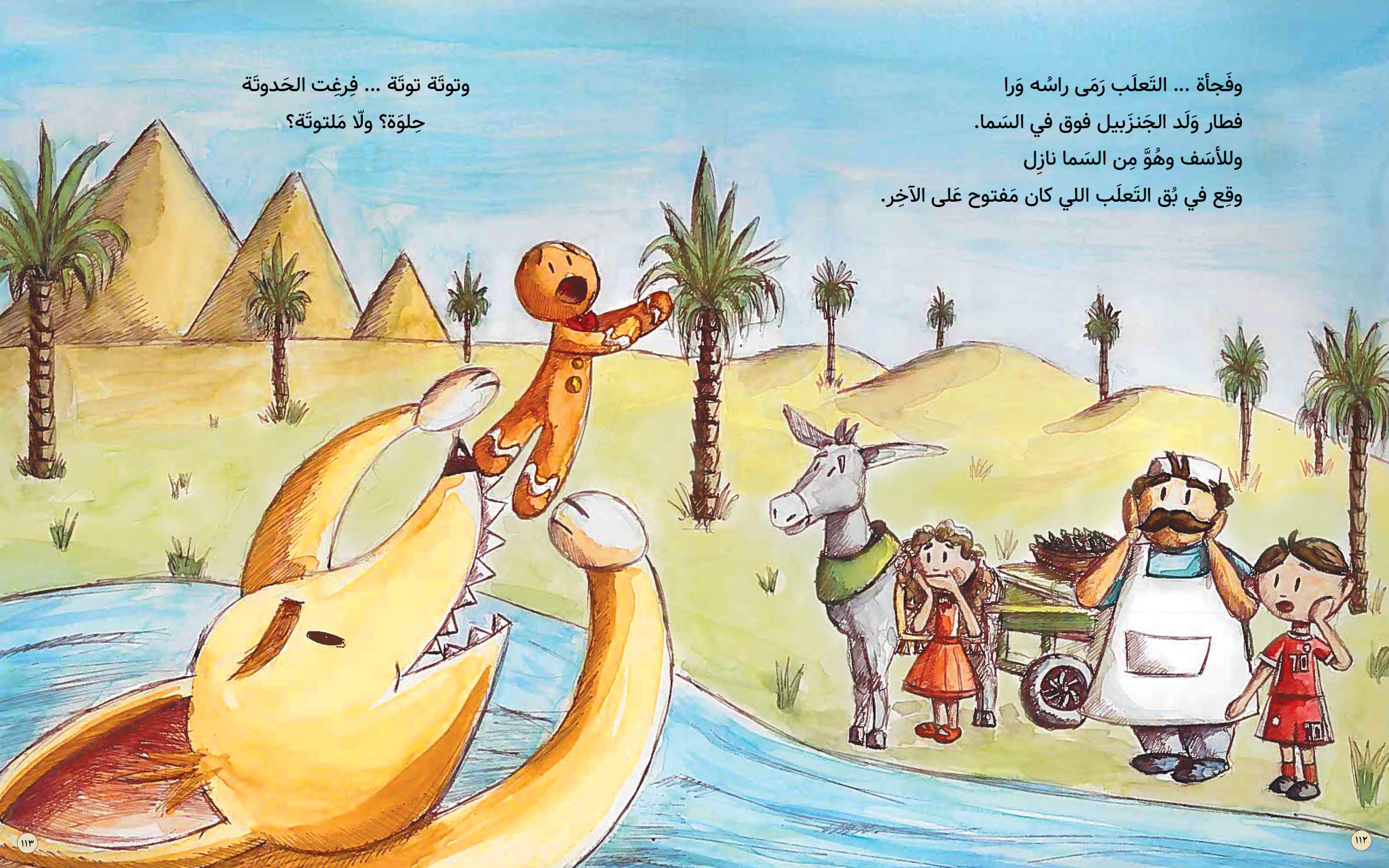

Even Cairo makes an appearance halfway through the compendium, as the gingerbread man races throughout the capital before ultimately being gobbled up against the dramatic backdrop of the pyramids.

Publishing in the Arab world

In 2012, Palestinian journalist Reem Makhoul relocated to New York with her husband, Stephen Farrell. Originally from Galilee, she, like Shendy, eventually shifted gears and took a career break when she had Sheherazade, her first child.

With Farrell being Irish, the onus was on Makhoul to introduce their daughter to the Arabic language and the identity she held so dear.

“I want my daughter to know the language of her music, her food, her culture, her clothes, the conversations in the village. You know, her grandparents, the plants we plant in the ground," Makhoul says.

"I want her to be able to communicate with them in their own language, and actually her own language because she is half Palestinian.”

One night in 2014, Makhoul was reading a bedtime story to Sheherazade, who was then nearly four.

“I started reading books in Arabic for her that friends and family brought to me from Palestine and Lebanon and Jordan," she says. But Makhoul missed the flow of Arabic storytelling.

"I had to read the story in Fusha in my head, each page, and then translate it into colloquial Arabic so that she understood the spoken Arabic words. It really bothered me. It didn't feel natural. It cut the flow for me and for her.”

Like Shendy, Makhoul faced the same problem: there were no suitable Arabic-language children’s books. Like Shendy, she took the DIY approach - but instead of reworking an existing book, she decided to make her own.

One night, after putting their daughter to bed, Makhoul told her husband: “I know exactly what we need to do. We need to write stories for children in colloquial Arabic.”

The couple set up a publishing house they named Ossass Stories (Ossass means "stories" in Levantine dialect), learning the trade from scratch and financing it themselves. Makhoul would work by day as a journalist and then research the publishing industry by night, drawing up cost analyses and searching for illustrators and distribution outlets.

“I was so excited that I felt like we were meant to do this," she says, recalling how she would stay up until three in the morning researching books written in colloquial Arabic.

“I was so surprised that I didn't find any because I thought: ‘I am so sure that there are so many people like me out there who totally thought about this, who totally went through this same process like me, but how come there aren't any books like this?’”

The first book they published in 2015 was The Girl Who Lost Her Imagination. Set in New York, it was inspired by Sheherazade’s own active imagination and written in the Levantine dialect.

Since then, the family have moved to Jerusalem. Ossass Stories published a second book, Where Shall I Hide? in 2017: both are now available in Levantine and Egyptian Arabic.

“If I teach my daughter Arabic, it's a gift for life. She will have more cultural and professional opportunities later on in the future,” Makhoul says. "I just want her to speak to me in my own language, and for me to speak to her in my own language."

Speaking in ‘our words’

The problem with reading material for very young children learning Arabic is universal. But the lack of age-appropriate learning resources is felt more keenly by parents raising their children outside the region.

Saussan Khalil, an Arabic language teacher at the University of Cambridge and a mother of two, says: "You don't have it around you. That's where it's such a problem for us outside of the Arabic speaking communities, that our kids are not exposed.

"They don't pick it up at home. You can't, the exposure is too little at home versus the [English] exposure at school."

British-Egyptian Khalil moved to Cambridge in 2014, when her first daughter Noura was two-and-a-half years old. Without an Egyptian community around them, she worried that Noura would never fully grasp her mother tongue.

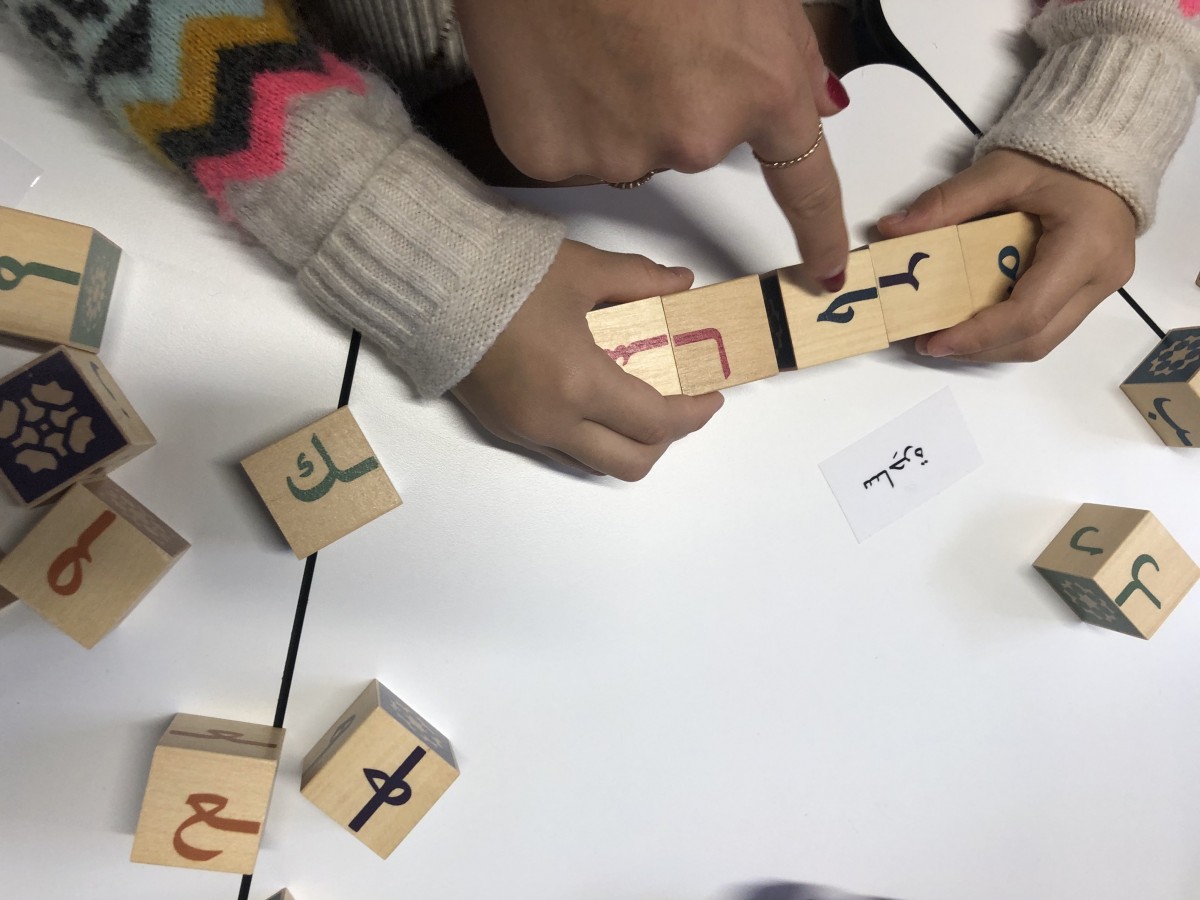

Khalil and her friend Mona El-Kheshen tried local Arabic groups for their young children, but found that the entry-level standard was too focused on writing for toddlers.

“It was actually Mona who turned to me after that and said: ‘Saussan, you're a teacher, teach [them] Arabic.' They say necessity is the mother of invention.”

More recently [Khalil] has introduced phonics-style learning... but the scarcity of resources for all ages continues to be a problem

Khalil set up a small weekly group, initially with just her daughter, El-Kheshen's two children and Khalil’s Spanish neighbour’s little girl, who was obsessed with ancient Egypt and wanted to learn the language.

Her approach was unique, conducting classes wholly in vernacular Arabic.

More recently, she has introduced phonics-style learning: Kalamna (Arabic for “our words”) now caters for around 60 students, from baby to adult, including weekly sessions for Syrian children who have resettled in Cambridge and whose parents want them to retain their native language.

But the scarcity of resources for all ages continues to be a problem. “If it's nursery rhymes and cartoons, and things like that, they’re all dubbed into Standard Arabic, it's very frustrating.”

Having once described herself as “the reluctant entrepreneur”, Khalil now also delivers masterclasses to aspiring teachers for their own Kalamna-style sessions and recently launched her first franchise.

“The problem is Standard Arabic isn't spoken anywhere.” Khalil says. “It's an ideological or theoretical standard. And so that's where linguistically the problems occur and pedagogically, as well. You're kind of creating artificial material and scenarios.”

Learners, she says, then get disheartened, because they can't use the language to speak to people.

"They get laughed at... it's very frustrating for them.”

The Enormous Turnip

In 2016, Khalil contacted Makhoul after discovering Ossass Stories and ordering a copy of its first book. Later she spoke to Shendy about how to add her Arabic translations into English storybooks.

Khalil recalls: "It sounds really extreme now but I remember the strength of feeling at the time that I just want a book in Arabic! And I guess Riham had the exact same feeling, so that’s how she came up with the idea. And a beautiful friendship was born."

From that point on, the three women communicated "constantly" Khalil says, mainly over email and social media. In February 2019 she set up The Spoken Arabic Initiative group on Facebook, as a forum to discuss projects, obstacles and "find support and encouragement when we just felt like giving up".

The three – based in the US, UK and the Middle East - finally met in person during summer 2019 when they discovered that they would all be in or near London at the same time.

"We felt like we’d known each other our whole lives and couldn’t believe we’d never physically met before," Khalil recalls.

There, on a windy summer’s evening in London’s Hyde Park, they walked and shared stories and advice. That meeting also precipitated Shendy producing her own anthology.

Shendy recalls: “I was with Saussan last August and she told me: ‘Do the book…’ And I said: ‘I’m not doing the book. No one’s going to buy the book.'"

“We were screaming in Hyde Park, me, her and Reem... And then literally, the second week of September, I was like: ‘Okay, I’m doing the book'”

- Riham Shendy

Indeed, the three were so engrossed in conversation that they missed the closing of the park and found themselves locked in.

“We were screaming in Hyde Park, me, her and Reem,” Shendy says. “And then literally, the second week of September, I was like: ‘Okay, I’m doing the book.’”

After pushing her to take the leap, Khalil helped Shendy put more argument into her academic thinking of the project and Makhoul gave her advice on illustration, printing and distribution, based on her own experience. "Reem helped a lot because she had the know-how."

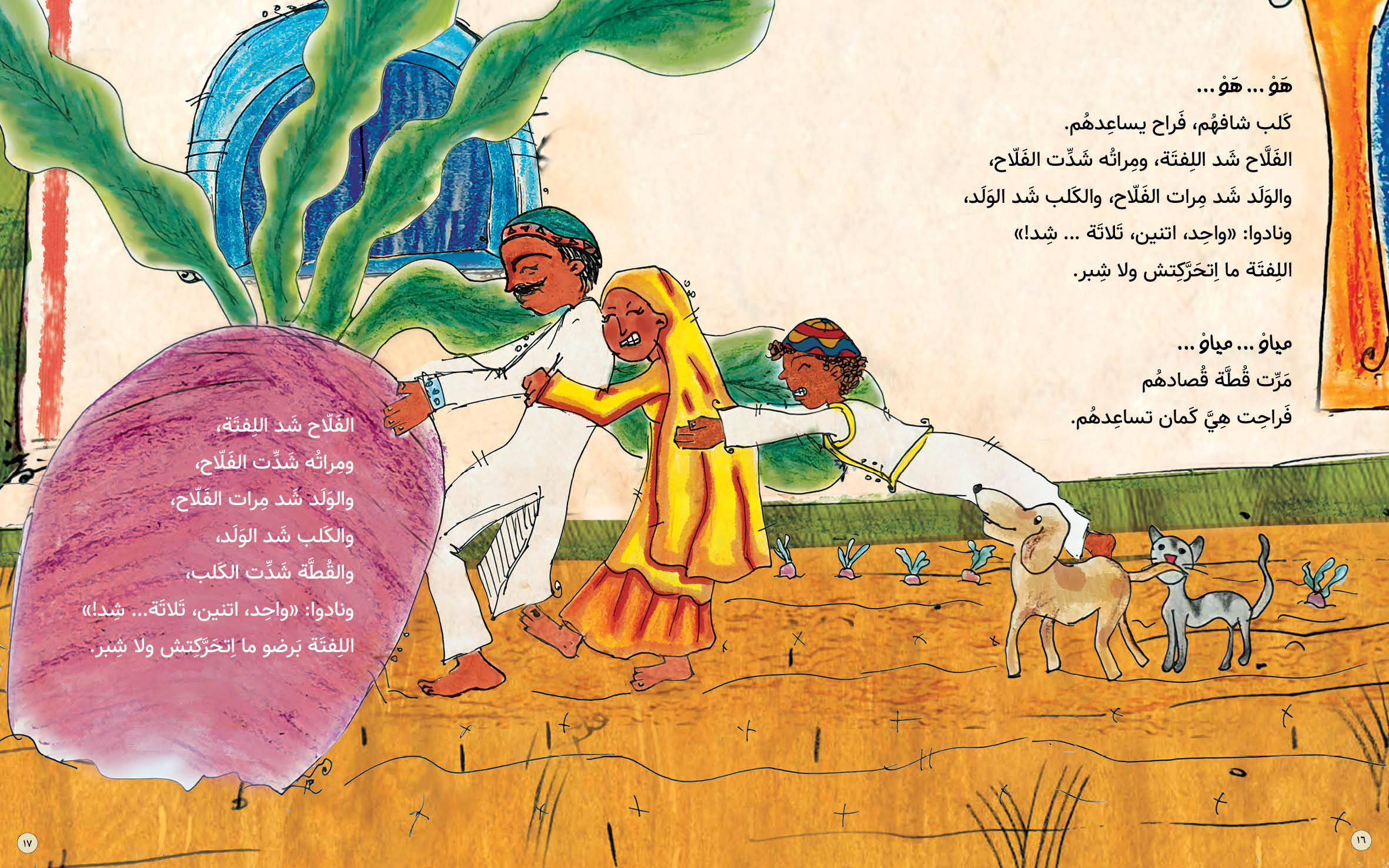

Shendy’s book opens with an Egyptian adaptation of the Russian folk tale The Enormous Turnip, which seems to symbolise the struggle all three women faced. Ateya, a farmer, is helped by his family and some passing animals as, one by one, they harvest a giant turnip that grew from rows of tiny seeds he had planted.

Then together they pulled and pulled, and the turnip suddenly flew out of the ground.

For the next month, whenever they were hungry, they would gather at the table, and eat from the turnip that they pulled out together from the soil

Shendy’s book has sold well in Egypt and shipping is now available to the US, with the rest of the world to follow soon. She has also started a video series on Facebook on the value of reading, based on cited scientific research.

“It's really a cry for people to look at this,” Shendy says. “We need this and nobody wants to do it.

"I'm not saying we should do a'amiya [spoken Arabic] forever for everyone. I'm just saying for the little ones - they didn't even go to school.

“To me this book is about: Is anybody feeling the pain like me, or not?”

“Kan Yama Kan (Once Upon a Time) – International Folktales in Egyptian Arabic”, is published by Tuta-tuta.com

“The Girl who Lost Her Imagination” and “Where Shall I Hide?”, are available from Ossass Stories in Levantine and Egyptian Arabic editions

Kalamna classes, usually held in Cambridge and Newcastle, UK, are currently available online in response to safety regulations following the Covid-19 pandemic

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.