France tensions explained in six questions

The past several weeks have seen France again face deadly attacks, which have in their wake highlighted the country's often strained rapport with its own Muslim citizens and with Muslim-majority countries.

Middle East Eye here summarises some of the major recent events, as well as some of the facts and concepts to - hopefully - shed further light on the tensions currently at play.

What is happening?

2 September: Trial opens for 14 suspected accomplices in the January 2015 attacks on satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and a Jewish supermarket in Paris, in which 17 people were killed during three days of bloodshed.

Assailants Amedy Coulibaly and brothers Said and Cherif Kouachi were killed by French police in separate standoffs shortly after the attacks. In a video recording, Coulibaly said the attacks were coordinated and carried out in the name of the Islamic State group (IS), adding Charlie Hebdo was targeted for its publication of cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

25 September: Two people are injured in a knife attack outside the former headquarters of Charlie Hebdo in Paris. The attacker is arrested by police shortly afterwards.

2 October: French President Emmanuel Macron makes a high-profile address on battling "radicalism" in France, saying his government would present a draft law aimed at strengthening secularism in the country, against what Macron described as "Islamist separatism".

"Islam is a religion that is in crisis all over the world today; we are not just seeing this in our country," he said, in comments that drew ire from a number of Muslim leaders.

16 October: A French teacher is beheaded outside his school in the Paris suburb of Conflans Sainte-Honorine. Samuel Paty had been targeted by a campaign calling for his dismissal after he showed a cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad during a class on freedom of speech. The assailant, an 18-year-old Russia-born Chechen refugee, was killed by French police near the scene of the attack.

In the wake of the attack, French authorities vow to take a number of measures to crack down against "separatism" and "enemies of the republic".

18 October: Two veiled French Muslim women are stabbed and wounded in Paris, close to the Eiffel Tower, following an altercation in which they are called "dirty Arabs". French police arrest two women over the attack, with racism listed as an "aggravating circumstance".

22 October: Two Jordanian citizens, a brother and a sister, are beaten in the French city of Angers after reportedly being insulted for speaking Arabic. Assailants have yet to be apprehended.

26 October: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan calls on Turks to boycott French goods, as he continues to criticise Macron's approach towards Muslims. A few days earlier, Erdogan had called for Macron to get a mental health check, prompting France to recall its ambassador from Ankara.

The call for a boycott of French products spreads in Arab and Muslim-majority countries, as a number of protests are held denouncing Macron's comments on Islam and further publication of caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad in the wake of the Paty murder.

28 October: The French government dissolves French Muslim charity BarakaCity - which Interior Minister Gerald Darmanin had previously called an "enemy of the republic," claiming the organisation maintains ties to the "radical Islamist movement" and "revels in justifying terrorist acts". The organisation forcefully rejects the accusations and vows to appeal the decision.

Meanwhile, Charlie Hebdo publishes a cartoon mocking Erdogan on its front page. Ankara's chief prosecutor launches an investigation against the proprietors of the magazine, as the Turkish presidency says it will take every legal and diplomatic step to hold to account those who insulted Erdogan.

29 October: Three people are killed and several others wounded in a knife attack at a church in the French city of Nice that is described by local officials as "terrorism". One of the victims was reportedly beheaded, echoing the 16 October attack. The assailant is shot and arrested by French police.

Meanwhile, a series of attempted attacks across France, including in Avignon, where a man reportedly affiliated to a far-right group was killed by police, leave the country on edge hours before a new coronavirus lockdown. Paris declares a nationwide state of emergency.

Hours after the Nice attack, a guard outside the French consulate in the Saudi city of Jeddah is wounded in a knife attack. The assailant, a Saudi citizen, is arrested.

What is the debate over cartoons about?

Cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad have sparked controversy worldwide since 2005, when a conservative Danish newspaper published a series of drawings of the prophet.

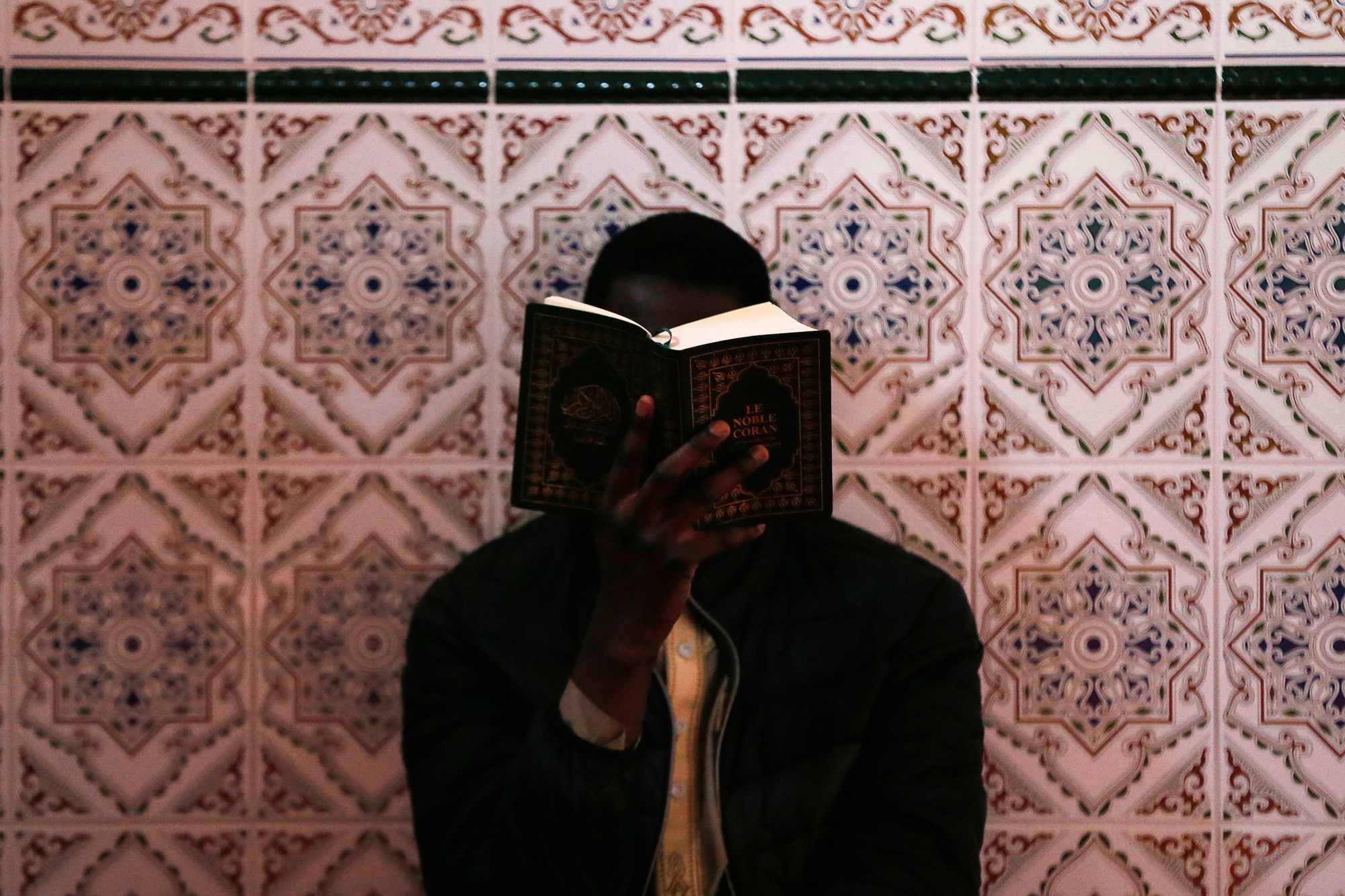

Muslim religious convention forbids visual depictions of the prophet, who is deeply revered in Islam. The fact that the vast majority of cartoons of the prophet have been demeaning or mocking has further inflamed tensions.

Critics of the cartoons say such depictions are offensive and constitute an attack on Islam, and deepen the marginalisation of Muslims in Western countries.

Charlie Hebdo has frequently published cartoons of the prophet, both before and after the deadly attack targeted the magazine, justifying the move in the name of freedom of expression and the right to blasphemy under France's particular strand of secularism, "laicite". The magazine has been subjected to criticism, as well as threats, over its stance.

Blasphemy is not punishable by law in France, although some legal cases have been filed over charges of insult and defamation.

In the wake of Paty's murder, Macron has vowed that France "will not give up cartoons".

What is laicite?

While many countries uphold secularism, France has its own particular version, laicite, which has been a cornerstone value of the state for more than a century, while anticlericalism has been a national tradition dating back to the 1789 revolution.

While the separation of religion and state has been an important issue in France, given the privileges and influence the Catholic church had under the monarchy before the revolution, laicite was first enshrined into law in 1905, despite not being explicitly named. The 115-year-old law put an end to the system of "recognised religions" under the Concordat of 1801, which placed the church under the mandate of the state.

The 1905 law officialised the strict separation between religion and the state, and guaranteed freedom of conscience and freedom of worship. The law, however, does not apply to the region of Alsace Moselle, which was occupied by Germany until 1918, and where churches continue to fall under the Concordat.

The French constitution of 1958 places laicite at the centre of the state's values, as its first article reads: "France shall be an indivisible, secular, democratic and social republic. It shall ensure the equality of all citizens before the law, without distinction of origin, race or religion. It shall respect all beliefs."

In the past two decades, a new interpretation of laicite has gained ground in French public and political discourse, which advocates a more stringent separation of religion and public spaces, not just state institutions, interpreting expressions of faith in public as contrary to France's secularist values. This debate has been central in the controversies surrounding Islam in France.

Who are France's Muslims?

France forbids census figures based on race or religion, making it hard to have reliable statistics or data, despite the country being believed to have the largest Muslim population in the European Union. Estimates vary between 4.1 million Muslims, according to the Observatory of Laicite in 2019, and eight million, with official research generally pointing to Muslims making up between seven and 10 percent of the country's 67 million inhabitants.

A 2019 poll conducted by the government Observatory asked whether respondents felt affiliated to a religion, as opposed to religious practice, and three percent of respondents said they felt ties to Islam, compared with 48 percent of respondents mentioning ties to Catholicism and 34 percent saying they had no religious affiliation.

While, again, trustworthy numbers are hard to come by, the vast majority of Muslims in France are believed to have origins in former French colonies in North and Sub-Saharan Africa, although other minority communities from elsewhere are also present.

The number of converts to Islam in France was, meanwhile, estimated by a sociologist from the National Institute of Demographic Studies (INED) to stand between 70,000 and 110,000 in 2011.

By the French government's own admission, suburban areas where immigrants from former colonies were agglomerated during the 20th century have been historically underserved.

"We have concentrated populations together based on their origins, we haven't sufficiently recreated diversity, not enough economic and social mobility... on our retreat, our cowardice, they [extremists] have built their projects," Macron acknowledged during his 2 October speech, adding that the French state bore responsibility for the "ghettoisation" of poorer areas where many Muslims live.

How is Islam discussed in France?

While secularism in principle applies to all religions equally, Islam has been in the crosshairs of the new conception of laicite, as a number of laws in the past 16 years have sought to take a stronger stance against religious expression in public institutions and public spaces.

While phrased without reference to any particular religions, a 2004 law banning "ostentatious" religious symbols in schools was widely interpreted as targeting Muslim head coverings, and has been used by school authorities to justify preventing some Muslim students from attending classes while wearing other items of clothing deemed to have religious connotations, such as long skirts.

In 2010, another law was passed stipulating that "no one may, in a public space, wear any article of clothing intended to conceal the face," with an explicit focus on Muslim face coverings such as the niqab or burqa. An estimated 1,000 to 2,000 women wear such attire in France. The United Nations Human Rights Committee found in 2018 that the niqab ban violated human rights.

The topic of Islamophobia has been a longstanding debate in France, with analysts arguing that the intersection of colonial history, race, religion and class have meant many French Muslims suffer from poverty, discrimination, and marginalisation within French society, in addition to seeing aspects of their faith criminalised by law and disparaged in public discourse.

Since 2015, polls have found more than half of respondents believe Islam to be incompatible with "French values".

Meanwhile, a growing number of political figures have rubbished accusations of Islamophobia, saying measures taken in the past decade, and particularly since the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attack, have aimed to fight Islamist extremism and preserve the values of the republic.

Increasingly, the expression "islamo-gauchisme," a derogatory term to refer to left-wing critiques of measures targeting Muslims, has gained ground beyond the far-right of the political spectrum, with Minister of Education Jean-Michel Blanquer recently claiming such positions were "wreaking havoc" in French universities.

How is Islamist extremism addressed in France?

In addition to a number of attacks inside France since 2012 committed by individuals claiming an extremist Islamist ideology, hundreds of French citizens travelled to Iraq and Syria to join the Islamic State group (IS), which between 2014 and 2019 controlled large areas of land in the two countries. In 2018, French intelligence agencies estimated that 730 French adults had joined IS in Iraq and Syria, with between 300 and 500 of them believed dead.

While IS has since lost control of these territories, the fate of foreigners detained in camps, the majority of whom are women and children, has remained a lingering question for many countries, including France, reluctant to repatriate citizens who may have had ties to the militant group. Some 370 French citizens, the vast majority of them children, were believed to be held in Kurdish-run camps in Syria as of July 2019, according to the Centre of Analysis of Terrorism (CAT).

France has passed anti-terrorism and other security-focused legislation at least once a year in the past decade, some legal experts have noted. Following a series of attacks in and around Paris on 13 November 2015, a state of emergency was implemented across the country for two years.

While French authorities have vowed to press forward with the anti-separatism bill following the Paty murder, MP Eric Diard, one of the rapporteurs for a mission on radicalisation in the public sector, has warned that "separatism" has yet to be formally defined by French authorities.

"It isn't well defined since we are presently speaking of religious separatism, but in the past we spoke of Corsican separatism or Basque separatism," Diard told France Info on 24 October. "A definition is lacking, and the Constitution protects freedom of conscience... Currently... we cannot prevent someone from living separately. What we can prevent are acts of separatism that threaten society."

A 2017 Unesco report on youth and violent extremism on social media also noted that no consensus had been reached in France on the definition of "radicalisation".

Meanwhile, members of the French government have been derided in the past for suggesting that some mainstream tenets of Islam, such as having a beard or praying, were signs of radicalisation that were worth reporting to authorities.

The lack of clear definitions of some of the most used terminology, some advocates have warned, could affect existing and future legislation and leave their application up to interpretation over what constitute threats to France's security.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.