France's cabinet greenlights 'anti-separatism' bill amid human rights concerns

French President Emmanuel Macron on Wednesday obtained his cabinet's blessing for draft legislation combating "radical Islamism" after a spate of attacks.

Critics, meanwhile, have expressed fears that the bill could further stigmatise the country’s Muslim population and yet fail to address some factors leading to radicalisation.

Macron argues that the legislation is needed to shore up France's staunchly secular system of laicite - the definition of which has been hotly debated in recent years - but the plan has further stirred up social tensions over the consequences for Europe's largest Muslim community.

"The enemy of the Republic is a political ideology called radical Islamism, which aims to divide the French among themselves," Prime Minister Jean Castex told newspaper Le Monde on Wednesday.

He argued that, rather than targeting Muslims, it aimed to "free Muslims from the growing grip of radical Islamism".

The legislation was discussed at a meeting of the Council of Ministers at the Elysee Palace, with Castex making a statement afterwards, arguing that the bill was not “against religions, nor Islam in particular”, but targeting “the pernicious ideology bearing the name of radical Islamism”.

"To the contrary, it is a law of liberty, a law of protection, a law of emancipation faced with religious fundamentalism.”

The draft law will head to parliament at the start of the new year for what promises to be a heated debate.

France's state council, which advises the government and the National Assembly on future laws, has already signalled that some parts of the bill, especially on education, may clash with the principle of freedom of choice enshrined in the French constitution.

What is in the law?

The text was originally titled the "anti-separatism" bill, deploying a term Macron uses to describe ultra-conservative Muslims withdrawing from mainstream French society.

Following criticism of that term, it is now called a "draft law to strengthen republican values", mostly laicite and freedom of expression.

The law was in the pipeline before the murder in October of Samuel Paty, a school teacher who was attacked in the street and beheaded after showing cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad in a class.

But the killing, committed by an 18-year old Chechen after a virulent social media campaign against the teacher, gave fresh impetus to the bill, prompting the inclusion of the specific crimes of online hate speech and divulging personal information on the internet.

Paty's death was one in a string of attacks in France in recent months, including a knife assault outside the former offices of the Charlie Hebdo satirical magazine and deadly stabbings at a church in the Mediterranean city of Nice.

The draft law sets out stricter criteria for authorising homeschooling of children over three years old, in a bid to prevent parents from taking their children out of public schools and enrolling them in underground Islamic facilities.

When asked by Le Monde whether he believed that the measure - which will affect 62,000 homeschooled children in France when an estimated 5,000 are believed to be potentially enrolled in such underground schools - was too broad, Castex replied: “It’s 5,000 too many.”

Doctors, meanwhile, would be fined or jailed if they performed a virginity test on girls.

Polygamy is already outlawed in France, but the new law would also ban authorities from issuing residency papers to polygamous applicants.

It would also require city hall officials to interview couples separately prior to their wedding to make sure that they were not being forced into marriage.

The bill does not include social policies to tackle what Macron has himself called the “ghettoisation” of poorer areas, where many French citizens of immigrant origins live.

While the president said in October that his government would seek to address “equality of opportunities”, Castex told Le Monde that such measures need not be voted on by law, but require the implementation of measures already taken by the government.

International criticism

The French government’s stronghanded response in the wake of the recent attacks has caused unease.

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet urged French authorities on Wednesday to “avoid taking measures that result in the stigmatisation of entire groups… or see their rights violated”.

Bachelet also evoked the “racism and ethnic profiling” of French security forces, following a number of recent high-profile incidents in the country that have further strengthened fears that current and future legislation will disproportionately affect minorities.

Meanwhile, the US envoy on international religious freedom said he was concerned by the legislation.

"There can be constructive engagements that I think can be helpful and not harmful," Ambassador Sam Brownback told reporters. "When you get heavy-handed, the situation can get worse."

Macron has become a controversial figure in some Muslim-majority countries, with several boycotting French products after his comments in October that the right to blaspheme would always be guaranteed in France and that Islam was "a religion in crisis".

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has called the draft law an "open provocation", while scholars at Egypt's prestigious Sunni Islamic institution, Al-Azhar, called Macron's views "racist".

Macron has also been forced on the defensive by critical headlines in influential English-language media, such as the Financial Times and the New York Times - critiques the French government has forcefully rejected, with Castex telling Le Monde they were “totally unfounded”, while maintaining that “we will never conflate radical Islamism and Muslims”.

Fears of repression

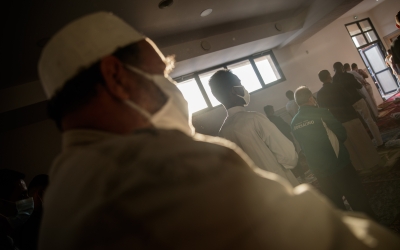

While France forbids census figures based on race or religion, making it hard to have reliable statistics or data, the country is believed to have the largest Muslim population in the European Union. Estimates vary between 4.1 million Muslims, according to the Observatory of Laicite in 2019, and eight million.

Some critics in France worry that the country’s decades-old focus on Islam leads to a conflation between Muslims and violent extremism, while failing to stop - or exacerbating - the latter.

'We are all targeted by terrorism. Terrorists make no differentiation between Muslims and non-Muslims'

- Yasser Louati, Justice and Liberties for all Committee

They say it fosters discrimination and Islamophobia, and misinterprets laicite - which at its inception was meant to separate the state from religious institutions, but has increasingly been redefined by some as the need to separate religion from the public sphere, with a particular focus on the visible tenets of the Muslim faith.

In the wake of the Paty murder, the French government dissolved Muslim charity BarakaCity and the Collective Against Islamophobia in France (CCIF), which monitors Islamophobic attacks across the country. Gerald Darmanin, France's interior minister, had called the two organisations “enemies of the Republic” and claimed they were supporting Islamic State-like ideologies. The two organisations have strongly rejected these accusations.

Last month, Macron also issued an ultimatum to the French Council of Muslim Worship (CFCM) to draw up a charter of "republican values" its member organisations and affiliates will be expected to comply with.

'Psychological trauma'

The CFCM agreed to create a National Council of Imams, which will reportedly issue imams with official accreditation that could be withdrawn.

The charter will state that Islam is a religion and not a political movement, while also prohibiting "foreign interference" in Muslim groups.

Yasser Louati, president of the Justice and Liberties for all Committee (CJL), told Middle East Eye in October that repressive legislation was only further fostering feelings of exclusion among France’s Muslim community.

“We are all targeted by terrorism. Terrorists make no differentiation between Muslims and non-Muslims - they’ve shown it at the Bataclan, they’ve shown it at Charlie Hebdo, they’ve shown it in Nice,” he said.

Dounia Bouzar, an anthropology researcher studying Muslim communities in France, had also warned at the time that policies focused on repression, as opposed to a multi-pronged approach such as the one she worked on with the government in 2017, fed the narrative promoted by groups such as the Islamic State (IS) that there was no space for Muslims in western societies.

“France is experiencing psychological trauma, but to lose complexity in our analysis is dangerous,” Bouzar told MEE. “It means losing our values, mirroring perhaps [IS]. It’s not a matter of self-righteousness, it’s that it could be counter-productive.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.