Barra and Zaman: How 'The Mummy' reveals a nostalgia for Egypt's lost past

The first thing I tell writer Youssef Rakha when he picks up the phone, him in Cairo, me in Beirut, is: I wish yours was the kind of reading I had been assigned while I was studying media and culture 15 years ago. We talk about how academia can ruin your love for the very subject you had been drawn to - and I thank him for managing to achieve the opposite with his essay.

An acclaimed Egyptian writer-essayist-journalist, Rakha’s novels, including The Crocodiles (translated into English by Robin Moger) and award-winning titles Paulo and The Book of the Sultan’s Seal (the latter translated into English by Paul Starkey), already showed a tendency for intertwining layers of history and politics in the context of Cairo, as well as the world at large. His novels also often experiment with the structure of storytelling.

Literally meaning “Outside and Time” in Arabic, the title of this 122-page essay refers to a real - or mythical - “abroad” in Egyptian Arabic, with the unmistakable implication of somewhere better. “Time”, or “a long time ago”, in this context reflects a nostalgia for Egypt’s past.

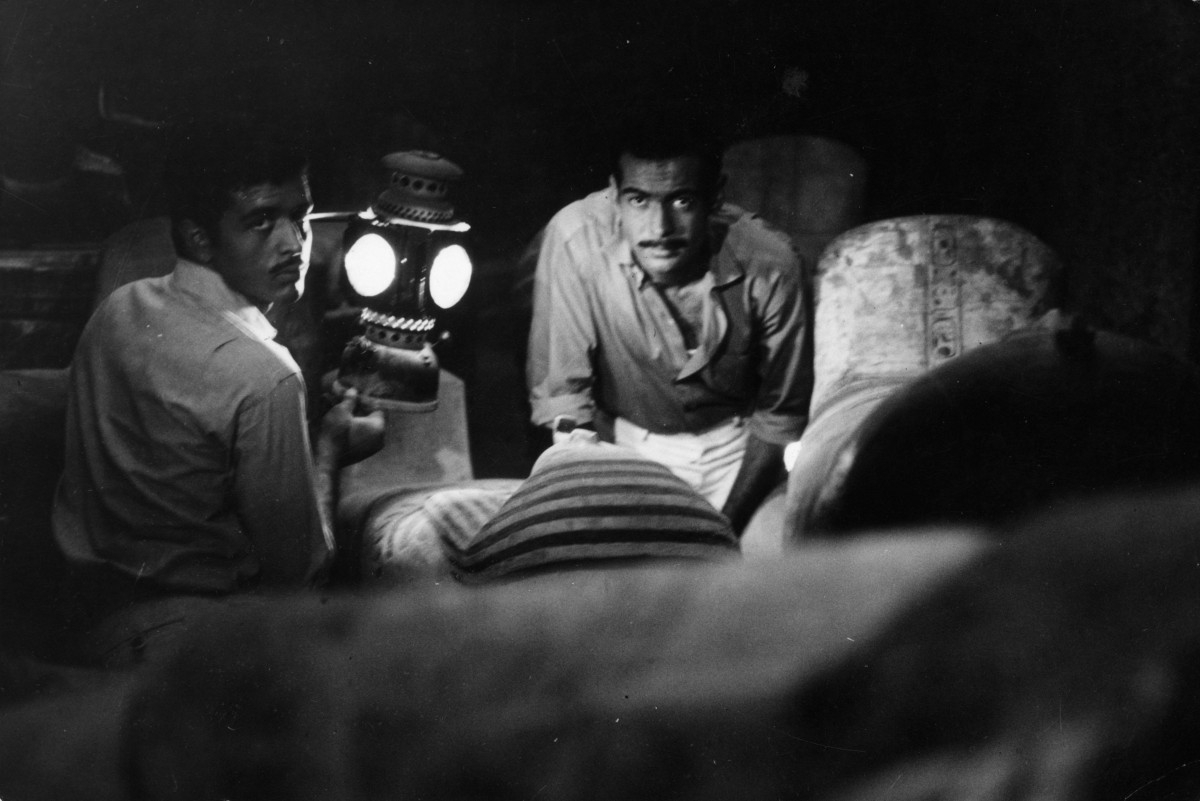

Ostensibly, it is a film analysis about the 1969 masterpiece The Mummy (also known as The Night of Counting the Years), Egypt’s nomination for the 43rd Oscars - although it didn’t get shortlisted - produced by legendary Italian neorealist Roberto Rossellini.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Set in 1881, just before the start of British colonial rule, The Mummy tells the true story of an Egyptian clan that had been robbing tombs for thousands of years. When Antiquities Service officials find mummies for sale in Cairo’s open market - stolen from a hoard of nearly 50 mummies, including their burial treasures known as the royal cache in Luxor - chaos ensues.

But as he watches the film, Rakha allows his thoughts to meander into a meditation on the impact of this cultural heritage on Egyptian identity, including his own. The essay therefore also functions as a literary refresher on topics ranging from the history of Egypt, to nostalgia, postcolonialism and the Arab Spring.

As experimental filmmaker Nezar Andary writes in his introduction to the book: “To read Barra and Zaman is not only an entrance to Shadi Abdel Salam’s film The Mummy. It is just as much … a window into ourselves.”

Reflecting on the revolution

Last year, Andary approached Rakha to write about the film for the Palgrave book series he was co-editing, Focus on Arab Cinema, a series brought to life to “challenge and provoke new forms of writing on Arab cinema”.

“The question for me [for this project] was, on the aesthetic level, this is acknowledged to be a masterpiece, and nobody is arguing with that,” Rakha tells MEE. “But what does sitting and watching The Mummy now, here in Cairo, imply? Why is this a significant thing?”

One of the influences on Rakha’s more recent viewing of The Mummy was the momentous past decade in Egypt’s modern history since the 2011 uprisings. The January 2011 revolution is pulled into the narrative of the essay by juxtaposing it with historical sites that appear in The Mummy and where people would converge during the revolution.

As he watches the scene where, following the discovery, the mummies are transported from Luxor to the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities at Bulaq in Cairo, Rakha fast forwards to 1902 when a new museum to house the antiquities was completed in Tahrir Square.

Rakha recalls the history of the square, previously named Ismailia Square, and connects it to the 2011 Egyptian revolution:

The place we convened on is in many ways modern Cairo’s dead centre. Tahrir (or Liberation) Square is what people baptised it in the 1919 Revolution but it wasn’t officially so named until the July Revolution [of 1952].

Arguably, the most fascinating parts in Rakha’s essay are the parallels between the way he approaches his ambiguity towards both the film and the 2011 revolution that elated and then paralysed Egypt, with both events described in a slightly sceptical, yet melancholic, manner:

Nearly a decade later it hurts to remember how, with more delight than either fury or fear, I too joined the first mass protests ever to take place in my lifetime, and how ecstatic I was when - apparently through unaided people power - they managed to bring down a head of state who had seemed inviolate.

“How I felt about the revolution was similar to how I saw the film,” Rakha tells Middle East Eye. “I was very excited about it and (felt) invested in it, although admittedly not for very long,” he says. “But at the same time a genuine tribute to it, a genuine recognition of its value has to acknowledge how it unravelled and why it unravelled. And while this is not a big part of the book, I think it’s very important.”

This unravelling, he argues, falls mostly on outside interference and forces, “barra-ness”, directing it and leading to the ultimate failure in the original, emotionally charged aims of protesters:

The Arab Spring often feels insufficiently grassroots and compromised. Is its focus on ideas that are popular barra [outside] at the expense of local reality why it failed?

'The Mummy' and identity

Revisiting The Mummy also allows Rakha to grapple with the Naksa, Egypt’s catastrophic defeat in the 1967 War two years before the film was released:

The Naksa was a huge, humiliating defeat that gave the lie to the regime’s claims about a powerful, in-control army. It spelled the end of a 15-year-old experiment in postcolonial nation-building, and it left writers and artists who had been invested in that experiment especially disoriented. If not born of that disorientation, The Mummy definitely reflects it.

Rakha argues that, while the Naksa was indisputably “a locus of distress”, the larger sense that Egypt, and the Egyptians, were in decline, had been pervasive for centuries:

When you say barra - “abroad” in Egyptian Arabic - the implication is automatically of somewhere better. Likewise zaman (“in the past”): the two components that combine in Shadi to make The Mummy possible - European education and nostalgia for Egypt’s past - can be described as preconditions for any 20th- or 21st-century discourse on Egyptian identity.

He also turns his focus to the role of colonialism in shaping Egyptian identity, when he refers to a scene in the film, which, he writes, “cannot help showing the political makeup of society”. In the scene, we are introduced to the central authority figure, who is French, while the quiet hero, an educated Egyptian, the “effendi”, defers to his authority:

Further on in the text, Rakha uses the effendi’s behaviour as a metaphor to illustrate the impact of the European worldview on Egypt’s national identity:

In Egyptology - as I suspect Shadi realised, more than he let on - the European worldview is so deeply embedded in national identity they might as well be the same thing. This is not false consciousness - it is trans-nationalism. And because barra is almost always bound up with zaman it is also doubly nostalgic: for the ancient past, and for the early colonial modernity that made that ancient past possible.

“This was really what the film was about and why the film is so fascinating,” Rakha tells MEE.

“It’s a way of bringing together these two poles of attraction that contemporary Egyptians are constantly orbiting. This sense of being orphaned, of really having no place in the world, having been born into this culture and needing to seek that place in the past.”

However, the identity that Rakha seeks to unearth, spurred on by what is unfolding on screen, is not just the Egyptian one, but also the writer’s own.

“The essay is very much about identity, as is a lot of my work, even if I try to run away from that. Because the obvious thing is that you’re born into a culture, a civilisation that is not the dominant civilisation of your time, and that immediately raises questions about your validity as a human being,” Rakha says.

“I’d like to think I’m also proposing a way of talking about identity that isn’t as narrow and politicised and activist-y as identity talk usually is these days.”

Further investigation guides him beyond Egyptian identity and his own, when he offers up the gentle realisation that cultural artefacts can open up infinite ways for all of us to wonder, negotiate and possibly understand who we are and our place in the world:

But what’s the alternative to revolution and patriotism? Maybe the way to resist is simply, in all our contradictory complexity, to be. Maybe it is to give up on delusions not of nationalism and authenticity but of equality, justice and the possibility of absolute emancipation - to confront, with bare-nerve bravery, our bondage to barra and zaman, who or what we are - so that we can think meaningfully about what we want to become.

Barra and Zaman: Reading Egyptian Modernity in Shadi Abdel Salam’s The Mummy, by Youssef Rakha, is available from Palgrave Macmillan

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.