Molokhia: How a humble green leaf both divides and conquers the Middle East

Warm, green and slimy in texture, molokhia is a leap of faith for those tasting it for the first time in a soup or stew, but its popularity across the Middle East suggests it's a dish that rewards those willing to give it a chance.

Despite its many variations, the dish is almost unique to the Middle East, North Africa and parts of eastern Africa.

Molokhia is so unfamiliar among western palates that even its English names "jute mallow" or "Jew's Mallow", among others, are unlikely to be widely recognised except among devoted gastronomers.

Prepared in soups and stews, the leaf of the Corchorus olitorius has a slightly bitter taste and creates a gooey liquid that clings to the spoon as it's raised away from the bowl.

That bitterness is often counteracted with beef or chicken stock and, depending on where it is prepared, chunks of meat or chicken.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The name "molokhia" is said to come from the Arabic malak, meaning "ruler". It is said Fatimid Caliph Al Mu’iz al-Din Allah ate the dish to deal with digestive illness.

A successor, Al-Hakim Bi Amr Allah, banned the dish ostensibly for its purported aphrodisiac qualities but probably for its association with a rival ruler. Members of the Druze faith, who revere Al-Hakim, are forbidden from eating the dish.

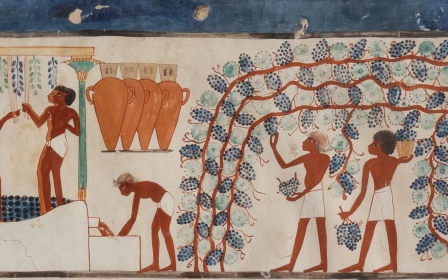

References to the dish also appear in Ancient Egyptian and Roman sources.

Given its high nutritional value, richness of texture and warmth, it's commonly prepared during the colder months.

Stock ingredient

Food writer Antonio Tahhan, a molokhia enthusiast, says he likes it best during the winter when he eats it several times a month, but says it is in fact an all-weather dish.

“Although molokhia season spans the hot summer months, the frozen and dried leaves make it possible to enjoy all year-round," the 35-year-old Syrian-Venezuelan based in Washington DC says.

"Nothing is cosier at this time of year than a bowl of molokhia cooked in homemade chicken broth.”

Tahhan's family is part of the Syrian diaspora that moved to Latin America during a wave of migration in the 1950s.

Syria had just gained independence from France in 1947, and was facing a series of short-lived coups until the Assad family took control in 1970.

The resulting instability forced many Syrians to consider establishing lives elsewhere.

Growing up, Tahhan's childhood kitchen was infused with the sights and smells of Aleppine staples, such as stuffed grape leaves (yabraq) and perfectly-shaped kibbeh simmered in a creamy yoghurt sauce (kibbeh labaniyye), one of the Levant's signature dishes.

Initiation into the world of molokhia, however, came the hard way for Tahhan, as there were important opponents of the dish within the family home.

“I never actually ate molokhia growing up," says Tahhan, adding: "My mum actually doesn’t like it and my grandmother doesn’t like it either."

The first time Tahhan tasted it was in 2010 in Aleppo, where he was studying Syrian food culture as part of his Fulbright-funded research.

His aunt Reina Khanji placed three pots - molokhia, white rice and shredded chicken - on a table covered in white lace cloth. Besides the dishes, she placed a smaller bowl filled with chopped onions drenched in vinegar, and encouraged Tahhan to eat.

Tahhan was blown away by the experience, and recalls taking second and third helpings.

“It was delicious, satisfying, refreshing and pleasantly tart from the quick pickled onions... it’s truly unique," he says.

Twists and variations

The plant itself is part of the okra family, and like okra (bamiyah in Arabic), molokhia can get quite slimy in texture. Although Tahhan explains that with the right cooking techniques, the sliminess can be controlled.

In Aleppo, he learned that not chopping or powdering the leaves and adding lemon juice helps to reduce the thickness of the stew.

Molokhia is usually prepared as a stew in a chicken or meat broth, but variants can end up looking like completely different dishes.

Tunisian molokhia, for example, has a denser consistency and is served with chunks of meat inside it, whereas the Cairene Egyptian version has a thinner texture, with shredded chicken served as an accompaniment rather than within the dish.

Garnishes and side dishes are another point of divergence. Many cooks prefer taqliyah, a sizzling blend of garlic and coriander, which adds depth to the dish. White rice or thick bread are also used to scoop up the gelatinous meal.

Other popular variations include an Egyptian version from the coastal city of Alexandria, which includes shrimp (rubiyan in Arabic) and another, also from Egypt, served with rabbit (molokhia bel arneb).

In South Sudan it its eaten with kisra, a thin, fermented flatbread, while in Eritrea injera (a sour flatbread) is used to soak up the stew. In the UK, some chefs have modified the dish and offer it with Turkish meatballs.

The plant has also made its way into Japanese cooking, becoming popular in the 1980s through migrants and visitors from the Middle East. In Japan, it is known as moroheiya and has been made into a noodle flavour, using molokhia leaf powder.

'There is something extremely beautiful and sacred in not promoting ingredients such as molokhia as a global superfood - it doesn't belong in a raw salad bowl, or in a smoothie'

- Meliz Berg, Turkish-Cypriot chef

It is also used as a seaweed alternative to make dishes like ohitashi, where the leaves are blanched and served with soy sauce.

Meliz Berg, a Turkish-Cypriot chef who grew up with the plant, says "I have loved it for as long as I can remember" and has fond memories of the lengths her family would go to to acquire the plant.

"I loved picking the fresh leaves off their stalks with my aunties in Cyprus when I was a child (and) the smell of the dried leaves as soon as my mum would take them out of the cotton pillowcases [used to transport the plant]," she says, adding, "I adore the unique, umami taste and texture of the dish itself.”

She still prepares molokhia the exact same way her mother and grandmother have done for generations.

Berg’s version of the dish is similar to the Levantine version but with a Cypriot twist: “We have a yahni tomato base to the stew and always cook the dish using the preserved dried leaves rather than fresh or frozen."

Her family uses lamb shoulder with no additional herbs or spices, just lots of tomatoes, onions and garlic. The ingredients are seasoned well with salt and lots of black pepper, and a generous amount of lemon juice.

"The red meat gives the lamb-based molokhia a luscious, thick gravy and, like most slow-cooked dishes, intensifies in flavour the following day,” Berg explains.

Like other dark, leafy greens, molokhia is packed with vitamins and has more calcium and phosphorus than kale. High in magnesium, it’s also a popular choice among parents looking to sneak it essential nutrients for growing children in one dish.

Benefits are said to include better digestive health and an improvement in sleep habits, but unlike other dishes famed for their nutritional qualities, such as quinoa, molokhia has not become popular in the West yet.

For people who grew up eating the dish, this might be a blessing.

Berg says: “There is something extremely beautiful and sacred in not promoting ingredients such as molokhia as a global superfood or trying to make it mainstream - it doesn't belong in a raw salad bowl, or in a smoothie.

“Sharing and educating the world about the numerous ways in which this one key ingredient is prepared … carries far more respect and weight than promoting it as a trendy superfood.”

Molokhia map

After returning from Syria to his DC home, Tahhan was still fascinated by the food and set about recreating it as accurately as he could.

Religiously following his Aunt Reina’s recipe, Tahhan invited a core group of friends from the Arab diaspora for lunch, serving them his family recipe of molokhia.

The event sparked passionate debate among his friends, who came from across the Middle East.

Tahhan’s Egyptian friend said the leaves should be chopped and not whole, like the way Tahhan had served it. A Palestinian friend queried his side of vinegar and onion, as in their home they only use lemon to add a sour touch.

Inspired, Tahhan created an online survey in an attempt to map all the variations, asking:

"Do people prefer whole leaves, or chopped?"

"Fresh leaves, frozen or dried?"

"What sides should be served with it?"

And importantly, "How slimy should it be?"

Since launching the survey on 20 March 2021, Tahhan has mapped out more than 800 responses, which he says represent "a beautiful reality".

The coolest research I’ve seen all year. @antoniotahhan has brilliantly put together a fascinating molokhia map tracing all sorts of ways to prepare and eat molokhia! https://t.co/D4ITlnPOxs

— Reem (@r_bailony) December 13, 2021

"(There is) an endless array of variations influenced by local cultures and traditions, often transcending rigid borders to make way for new, yet familiar flavours; innovative, yet traditional practices," says Tahhan.

His findings show that the national divisions on how molokhia should be prepared are not as rigid as the debates at his dinner parties seem to suggest, and that a lot of respondents were open to new methods of preparation borrowed from other countries.

"For example, 76.9 percent of Syrians keep the molokhia leaves whole, whereas 75 percent of Egyptians insist the leaves must be chopped," he recalls, asking whether, given such differences, molokhia can be considered a single dish or a family of related dishes.

"There are all the variants, which led me to wonder, when does a variation of a dish stop being that dish? Is there really one dish called molokhia?"

When Tahhan told his Jeddo (grandfather) about his molokhia map, he found out that his grandfather used to drive more than an hour from his home in Venezuela to his brother’s house to eat molokhia prepared by his sister-in-law.

The last time his grandfather had molokhia was in 1984, when the same brother and his wife moved to Lebanon.

Tahhan prepared his aunt's version for his grandfather, with whole leaves and plenty of the quick pickled onions.

Trying the dish after a 37-year-long wait in 2021, his grandfather was confused and somewhat dismayed.

This was not the molokhia he remembered. According to Tahhan's grandfather, the best versions of molokhia came from Egypt and Sudan. Tahhan recalls that after a couple of bites, he said: 'The leaves should be chopped.'"

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.