Exploring the forgotten scents of ancient Egypt

Scents have always been an important part of ancient Egypt. Hatshepsut, the 15th century BCE queen of Egypt and someone seen as an intermediary between the gods and the country's people, was tasked with ensuring that the kingdom was always filled with pleasant scents.

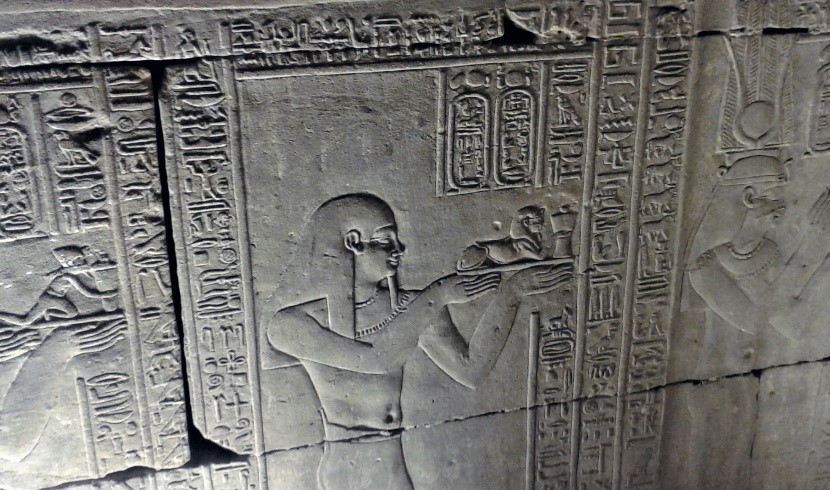

Scents are even mentioned in the inscriptions found at the Temple of Edfu, where the Egyptian king Ptolemy X is said to have anointed himself with the best perfumes as part of his daily morning rituals.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The Ebers Papyrus, one of the oldest medical papyri of ancient Egypt, says that good scent fills the rooms of a noble family’s home, impregnating their clothes.

From this, it is clear that scent was a key part of the daily life of ancient Egyptians, and remains an integral part of the human experience, offering valuable clues about many aspects of the past, such as rituals, cuisine, perfumes, hygiene, trade and medicine.

By delving into how ancient Egyptians made sense of the world through smell, we can learn more about certain practices and social hierarchies of the time, and their perception of the world.

Filling in the sensory gap

Despite smell revealing a lot about people and the climate of ancient Egypt, Egyptology has so far not recognised the full potential in the study of scents, and what it can tell us.

“It’s very important to understand the ancient Egyptians through smell, because it was extremely significant in their culture. If we disregard this part of their culture, then we are disregarding a huge part of it,” Dora Goldsmith, an Egyptologist at the Freie Universitat Berlin and leading researcher on the topic, told Middle East Eye.

Goldsmith, who translated inscriptions found in the Deir el-Bahri, Edfu and the Ebers Papyrus, noted that most publications about archaeological findings in Egypt focus on ancient Egypt only visually.

Whether they be about coffins, burial chambers, temples or cities, publications rarely talk about scent. Yet this is beginning to change, with some researchers trying to fill in the gaps in this largely odourless landscape, in a variety of ways.

Goldsmith is combing ancient texts for references to the world of smells, even going so far as to recreate ancient Egyptian perfumes and smellscapes. Others are searching for archaeological evidence in the Egypt. Some are trying to discover the contents of ancient objects by analysing scent molecules that have been preserved to this day.

“The three ways yield different kinds of information,” Barbara Huber, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany, told MEE.

“By using scientific analyses together with information from ancient texts, visual depictions and the broader archaeological and environmental records, we can open up new aspects of past olfactory worlds, our changing societies and cultures, and our evolution as a species,” Huber noted.

Popular ancient perfume

Strategically located in the Nile Delta, Thmuis became a major centre of perfume trade in the ancient world. Exotic spices from India, the Arabian peninsula and other parts of Africa flowed to the city to fuel its most important industry. And its production was later shipped to Alexandria and across the Mediterranean.

In recent years, archaeological work led by Jay Silverstein and Robert Littman is starting to unearth part of that glorious past.

“It was the most important industry in this area,” Silverstein told MEE. “There was a lot of money to be made, you had the most talented perfumers and merchants centred here, and they were able to get all the spices from around the world.”

Among the discoveries the mission co-led by Silverstein has been able to make since 2009 is a Hellenistic complex associated with the manufacture of perfume bottles, made up of 20 kilns and ancillary structures including wells, aqueducts, basins and ovens.

According to Silverstein, these elements suggest this was a place dedicated to liquids, a hypothesis the team hopes to confirm later this year with the results of a chemical analysis of samples from the site.

“It is pretty clear to me that it’s a perfume manufactory. It wasn’t consistent with any other type of factories we looked at,” Silverstein noted. “[And] it was found associated with a treasure, which suggests it’s the house of a wealthy merchant. All the pieces point in that direction.

“I suspect there were many workshops,” he added. “Probably [the industry] was originally controlled by the priests of Mendes, but eventually fell more into the hands of private entrepreneurs, who took more control over the business."

In particular, the Thmuis-Mendes area’s flagship product was a perfume called Mendesian, which was the most popular fragrance in the ancient world for centuries. And although there are no literary accounts of it from ancient Egypt, Greek and Latin references do mention it as far back as at least the mid-first century CE.

Key ingredients

Goldsmith has documented Greco-Roman sources consistently listing four ingredients for Mendesian perfume: myrrh, cassia, resin and oil of balanos (most academics believe this is a species of moringa, others desert date oil). Some accounts also mention cinnamon. Quantities and methods of production, which Goldsmith and scholar of Ancient Greek science Sean Coughlin have tested, are preserved in a document from the seventh century by the Byzantine physician Paul of Aegina.

“It was not easy [to reconstruct it] because the Mendesian is only mentioned in Greco-Roman sources, so in Greek and Latin, and they are not really recipes. These sources describe what they claim to be Egyptian perfumes,” Goldsmith said.

“But it was also very exciting, because I tried to track back some of the ingredients they mention to ancient Egyptian perfume ingredients. And I found out that some of them the Egyptians did use, but not all of them.

“The way Greeks treated Egyptian recipes was very flexible. They retained some ingredients, but they also changed a lot. The study of how perfume recipes changed from the Egyptians to the Greeks can be referred to as transmission of knowledge in perfumery.”

Based on this and other information she has collected over the years, Goldsmith has been able to recreate numerous products from ancient Egypt: from four temple perfumes to remedies from medical texts. And she noted that they could work perfectly well today.

“I know for a fact that all these products are antibacterial [and] antiseptic, they are also really good for your skin, so they would definitely work [today],” she said.

Smellwalks and smellscapes

Another way to enter the world of ancient Egyptian smells is through what Goldsmith calls smellscapes, which she reconstructs based on written documents.

The researcher, who has recently devoted a paper to this subject, explains that the written references have certain limitations, including not enough sources from a simple place and period, and perceptions in ancient texts not being fully representative of the entire society.

However, based on written references dating from the First Dynasty (2925-2775 BCE) through the Ptolemaic period (305-30 BCE), Goldsmith has been able to reconstruct a smellwalk in an idealised ancient Egyptian city.

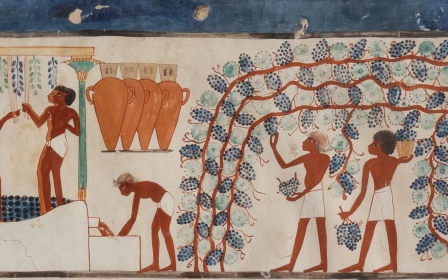

A good first stop on this route is the temple, where the scents of incense, myrrh, honey, perfumes, scented cloth and floral offerings from the sanctuary mix with the strong smell of roast meat, bread, cake, milk, beer and wine coming from the hall of offerings.

The king’s private chamber is another must stop. There, his servants anoint him as part of his morning rituals “with the finest perfumes made out of the costliest ingredients in order to enhance his divine appearance”. And not wanting to be less refined than him, the queen also anoints herself with aromas that will leave a pleasant trail wherever she goes.

'People would represent all sorts of things through their scents, through the perfumes they used; they would communicate their social status in society'

- Dora Goldsmith, Egyptologist

Royal gardens were also filled with fragrant trees, flowers and herbs, both to satisfy the gods and to fill the city with a pleasant aroma, Goldsmith writes.

“People would represent all sorts of things through their scents, through the perfumes they used; they would communicate their social status in society,” she said.

“By emitting a strong and pleasant scent, the queen is manifesting her presence and high status in society.”

The final stop on this route takes us into the homes of ancient Egyptians.

In the home of a lower-class family, Goldsmith writes, the smells of sweat from the artisan or peasant who has spent the day working outside mingle with that of a deodorant made of incense, chamomile, cypress cones and myrrh, used to eliminate stench, especially in the summer.

And in a noble family’s house, the rooms and clothes will instead be impregnated with the pleasant smell of burning kyphi, a fragrance made from products such as dry myrrh, cypress cones, incense, wood of camphor tree, and mastic.

Their kitchen is at the same time flooded with strong smells released by the dishes cooked by servants, contrasting with the scent of the garden and its blooming flowers and blossoming twigs, a perfect setting for an intimate stroll.

“There is a lot of communication through smell; the smell means something. There was value attached to it in Egypt,” Goldsmith said. “In order to really understand [ancient] Egyptians, you need to understand their olfactory culture. It was a very big part of their everyday life.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.