Syria: Abandoned by their countries, children of Islamic State women educated in prison

Children's laughter escapes from a prefabricated building where the air conditioning runs at full blast in the July heat. Inside, there are about 20 girls and boys, between eight and 10 years old.

"Who among the girls can tell me the story of the three little goats?" asks their Kurdish teacher, who has adapted the famous story of the three little pigs. Sitting behind her desk, wearing a green T-shirt with printed watermelons, Kahina raises her hand and answers: "There are Ramla, Thalja and Ramada. One made her house out of straw, the other out of wood, and Ramada built it out of stone." The whole class applauds, and Kahina smiles shyly.

The little girl is nine years old and British. Her mother, an ex-member of the Islamic State (IS), has been incarcerated for several months in this prison in Hasakah, after being arrested in the Al-Hol camp.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Three adults are in charge of Kahina's class, but they seem overwhelmed. After a few minutes, the children leave their desks and prefer to play with their friends. “Our job is tough because each student comes from a different country," Solin, one of the teachers, told MEE.

The children are different nationalities. Some speak Arabic well, others do not at all. One little girl from Tajikistan didn't understand anything at the beginning of classes. "She was screaming, 'Leave me, leave me!' Finally, her older brother helped me communicate with her," Solin adds.

Few hours of freedom

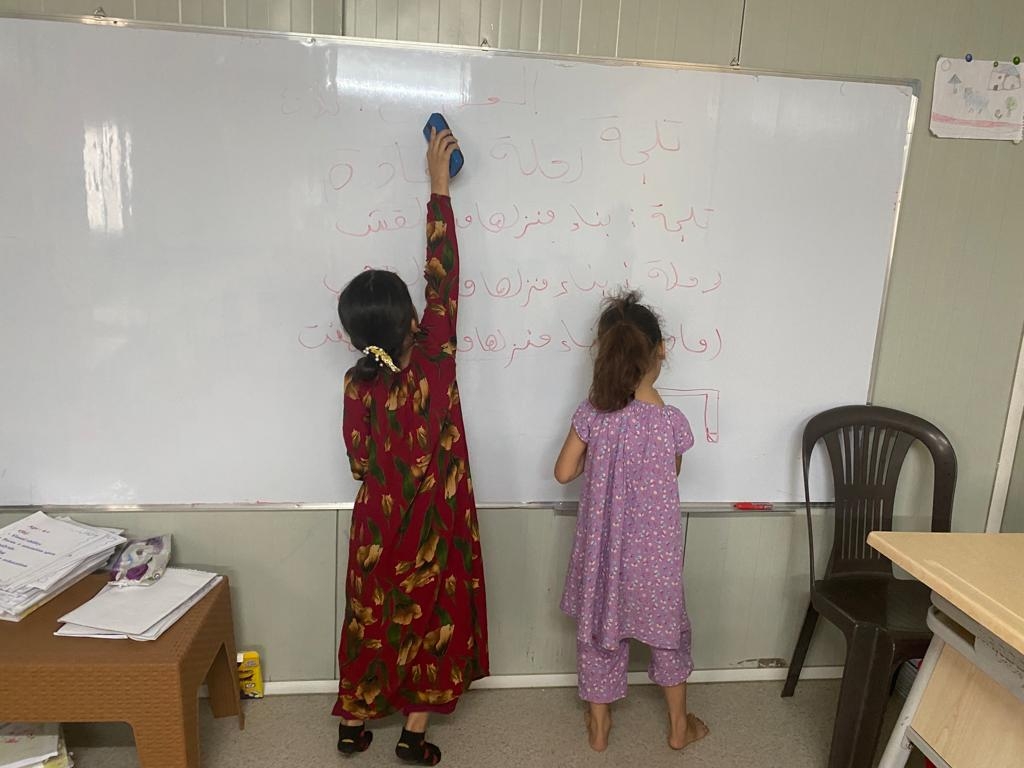

Five times a week, starting at 9am, the 71 children are taken out of the cells where they sleep with their mothers to spend a few hours in the education centre. Behind its heavy metal door, several prefabs are spread around a courtyard whose walls are covered with drawings that are already beginning to fade. In the middle is a small swimming pool without water. In the middle of summer, the heat is stifling; but it is even more so in the prison cells, ventilated only by small openings.

This centre, managed by the local Kurdish authorities, was built in 2020 to care for children of detained women who are suspected to be ex-members of IS. Many are foreign nationals, and are held outside any legal framework, without trial or access to lawyers, according to Human Rights Watch.

The children are between two and 12 years old.

"I am from Morocco," said a boy as he left his classroom. Next to him, his friend laughs and adds: "I'm from Tunisia." Another boy points at a classmate and says: "She's French.”

Some speak Arabic, sometimes with an accent from Raqqa, the former Syrian capital of IS. Among this group of little boys there is also a Turk, an Indonesian and an Uzbek. People of many nationalities joined IS when the group controlled part of the Syrian territory. Today, it no longer has control over any territory, but thousands of its members are still in northeast Syria, held by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), in prisons or camps. With them are thousands of children.

“We can't let these children spend their entire days in prison with their mothers," Dina, the head of the centre, told MEE. "It would not be fair. They are innocent children.”

'We try to teach the children human values, but then they return to their cells with their mothers, telling them not to trust us because we are infidels'

- Dina, Kurdish teacher

The children languish in the prison for an indefinite period. Some have just arrived, and others have been there for almost a year. Many suffer from deep trauma after seeing several family members die in airstrikes. Others are indoctrinated by their mothers, who continue to teach the ideology of IS to them, Dina claimed.

These children are sometimes difficult to take care of, she added. "This is one of our biggest challenges. We try to teach the children human values, but then they return to their cells with their mothers, telling them not to trust us because we are infidels."

Recently, the centre received death threats from IS cells still present in Syria. The head of the camp and the teachers had to leave their posts and be replaced urgently. However, according to the teachers, their efforts are paying off, especially with the youngest children. Children quickly accept to sing and draw even if their mothers forbade them since birth, Solin told MEE.

"Many of them feel happier as soon as they walk through the centre's door. I can feel it, and they are better. It is complicated when classes are over, and they are told to return to their cells. They don't want to! They want to stay and play, like all the children in the world."

Local authorities overwhelmed

All the children are foreigners, and many countries, especially in Europe, are slow to repatriate them.

Since 2020, many IS-linked Syrian women, for example, have been released by the local authorities after agreements with local tribes.

"Concerning the local families who are ex-members of IS, the Syrian ones, we are obliged to take care of them and to help them find a place in society," said Abu Ali Najeb, a senior SDF member.

"For those who came from Europe or Africa, we have to take care of them too, but we don't have enough financial means," he told MEE from his office in Raqqa. "It is their countries of origin that should be responsible for them.”

In early July, France repatriated 35 children with their mothers who were held in the Roj camp. It was a first. But according to the French authorities, there are still about 100 female ex-IS members and nearly 250 children in northeast Syria.

The United Kingdom still refuses to bring back its IS-linked citizens. Tunisia and Morocco have been announcing for several months that repatriations will take place, but for the moment, no operation has been carried out.

In the northeast of Syria, local authorities keep repeating that they cannot take care of these foreign families forever.

"Our centre is not a solution that can last," sighs Dina, who is in charge of the children in Hassake prison. "That's why each country must bring back its children. It would be a great relief for us. If they stay, they will want revenge."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.