Chickpeas, budgies and Hafez: How fortunes are told in the Middle East

From looking at clouds to checking out the direction an arrowhead falls through the air, people have long sought signs to predict the future; hoping for good tidings and waiting in fear of bad omens.

Scientists may rubbish the idea that anything beyond measurable data can portend the future, but that has done little to dampen popular interest in traditions like reading tea leaves or horoscopes.

For millennia, entire fields of study have developed around fortune telling; looking at patterns in the clouds is aeromancy, while divination using arrows is known as belomancy. Aleuromancy was the ancient Greek practice of observing how flour settles on water to predict what lies ahead.

In the Middle East, ancient Mesopotamians turned to astrology to predict the future, guided by the belief that the stars above were the abode of gods and therefore contained divine mysteries.

The Ancient Egyptians, like other ancient Near Eastern peoples, practised dream incubation, which involved a person trying to induce a dream that would reveal information about future events.

Oracles would also be sought out by important men to catch a glimpse of their futures. Those turning to these ancient fortune tellers included Egyptian pharaohs and Alexander the Great.

The monotheistic religions were less tolerant of attempts to predict or influence the future, with all three Abrahamic faiths explicitly prohibiting fortune telling.

The Book of Deuteronomy calls the practice "detestable" and, in Leviticus (19:26), the Bible states: "Do not practise divination or sorcery." In Islam, divination is considered a major sin and an affront to God, who alone should determine what is to come.

Those who practised fortune telling were said to be working with djinn; spirit beings found in ancient Arabian belief systems who were made of a smokeless fire and had the ability to transcend time and dimensions.

There were nevertheless some exceptions to such prohibitions. Dreams, for example, were thought to contain clues to what may happen in the future, but these were believed to have come from God directly and not by other forms of divination.

Those religious prohibitions have not stopped the popularity of fortune telling in the Middle East, with many forms of the tradition popular across the region.

Turkish astrologer and psychic Deniz Batuk has been reading coffee cups for 23 years. He tells Middle East Eye: "People come to me before making business decisions, before buying or selling a house, love matters, or not being able to say goodbye to loved ones when they've passed away."

Here, Middle East Eye takes a look at some of the most popular forms of fortune telling in the region.

Tarot cards

Tarot cards first became popularised in medieval Italy in around the 14th century as playing cards, but their origins have been attributed to eastern countries, such as India and Egypt. By the 1700s they were being used for divination, after they were adopted by occultists, who sought to add to their mystery by giving them an origin in far-off and exotic places. Other claimed sources include the Jewish Kabbalah movement, as well as the Mamluk rulers of medieval Egypt.

Today, for those seeking a glimpse into their future, there are several specialised cafes dotted around the base of Istanbul’s historic Galata Tower, discreetly displaying a sign advertising tarot readings in their windows.

The reader, sometimes a clairvoyant – someone who claims to be able to see the future – will ask the client to shuffle the cards, which allegedly transfers their energy to the deck. A specific question is asked and the reader interprets the arrangement of the cards, with signs like the Empress signifying maternal influence, or the Fool paving the way for new beginnings and endings.

Coffee cup readings

Deniz Batuk learned to read used coffee cups as a child in Istanbul, telling Middle East Eye: “I would watch my grandma peer into the cups of family members for fun.”

He says a sense of intuition led him on a spiritual journey towards the practice. Now studying psychology and counselling in Sydney, Batuk says he wants to combine his professional qualifications with divination practices to offer a more holistic and spiritual form of therapy.

Known as tasseography, cup reading is the study of dried patterns left behind on a used coffee cup to predict the future. Despite Islam’s prohibition on fortune telling, the practice is deeply rooted in Turkish culture, dating back to the rule of the Seljuk Empire, which ruled most of Anatolia, Iran and Central Asia in the late 11th century – even before the spread of coffee in the region.

The later Ottomans even employed a palace astrologer, known as a muneccimbasi, who would be an expert in a number of divination practices, such as coffee cup reading. Ottoman bureaucrats and military planners would consult the expert before making important decisions.

Batuk sees around 80 clients a month, either virtually or in person, around two-thirds of them women. His clients come from different religious backgrounds, with some consulting him secretly and others being more open about their belief in the practice.

In today’s practice, coffee is traditionally prepared in a cezve, a small pot with a long handle, with only enough prepared for one small cup. Once the drinker has finished the beverage, the cup (or fincan) with its remaining residue is turned over in the saucer. Some suggest turning the cup three times while saying the words: “Neyse halim, ciksin falim”, which means “May the fortune show what my circumstances hold.”

Others insist the cup must be flipped over to face the drinker, or that the handle of the cup must be facing the drinker. The fortune teller then reads the pattern left behind by the residue, interpreting shapes as symbols or letters. Readings are purely subjective, with two cup readers potentially giving starkly different responses.

Fortunes of Hafez

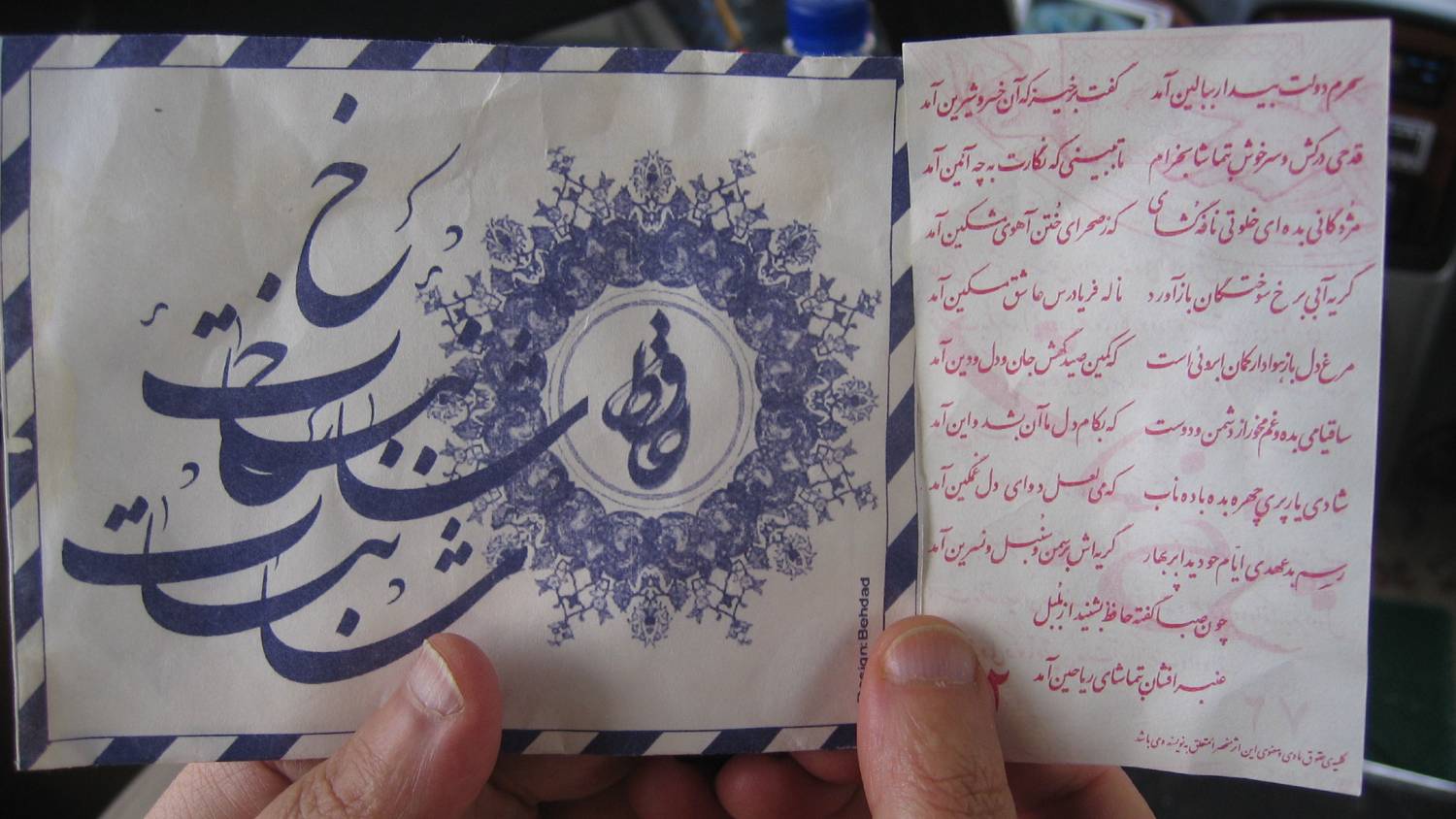

Khwaja Shams-ad-Din Muḥammad Hafez-e Shirazi, better known as Hafez, was a 14th-century Persian poet from the city of Shiraz. His ollections, such as the Lisan al-Gaayib (The Tongue of the Unseen) and the Divan-e-Hafez are found in many Iranian homes today. His work is deeply imbued with Sufi and mystic themes and touches upon topics as varied as love and loss.

Given that breadth, a tradition has developed in Persian-speaking countries, such as Iran and Afghanistan, where a verse from Hafez's poems is selected at random in the hope that it contains something relevant to the reader’s life and future.

Other books, such as Rumi’s Masnavi, the 16th-century Falnama: The Book of Omens, and even the Quran are also used in the same way.

A variation of the practice found on the streets of Tehran involves a man carrying a palm-sized box containing verses of poetry or scripture, as well as a budgie perched on his shoulder. A customer asks a question of the man, who prompts the bird to pick a card at random. The selected card purportedly carries an answer relevant to the client.

Chickpeas and fava beans

Favomancy is the practice of using beans and other pulses to predict the future by scattering them and looking for patterns in the way they have spread out.

Popular in Bosnia and Russia, the practice is thought to have originated in the Middle East, most likely in Iran, where similar traditions exist.

In the Bosnian tradition, 41 beans are used and the ritual is known as bacanje graha, or “bean throwing”.

A female fortune teller, known as a faladzinica, recites verses from the Quran over the beans before throwing them in three bursts, representing the past, present and future.

While locals claim the practice is rooted in Islam, orthodox interpretations of the religion largely dismiss soothsaying.

Numerology

Like other forms of fortune telling, numerology's origins are ancient, with scholars tracing it back to early civilizations in Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) and Egypt.

The basis for the practice is assigning letters a numerical value and trying to look for signs in words, names and a person’s date of birth that are relevant to his or her future.

The Chaldeans in Babylon were early practitioners of numerology, and possibly influenced the Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras, who developed his own set of numbers and codes to determine one's future.

Modern numerologists use a system to decode people's names and dates of births to better understand one's character and destiny. The final soul number is always a single digit, with number one signifying leadership and number five linked to insight.

Palm reading

The contemporary form of palm reading spread to the Middle East with the migration of the Roma people, who have their origins in the Indian subcontinent. Forms of the practice were, however, present in ancient Mesopotamia, Persia and Ancient Greece.

The basic technique involves looking at the lines on a palm for distinctive features that may reveal information about someone’s personality or their future.

Forbidden in Islam, the practice is still popular in majority Muslim nations, with Iranians calling it kaf bini (palm gazing) and Arabs ilm al-asarir (the science of palm lines). It involves the reading of six major lines on the hand: the table line, wisdom line, honour line, fate line, life line, and wealth line.

Predictions are made about everything from the age of a person at their marriage, the number of children they have, the age at which they will die and whether they will have wealth or live in poverty.

Jewish Kabbalists cite a 13th-century sage, Asher ben Saul, to justify their use of the practice, which would otherwise be prohibited in mainstream forms of Judaism. “Through the lines on the hands the sages would know a man’s fate and the good things in store for him,” Saul is reported to have said.

Some Christian scholars also accept the practice based on readings of the Book of Job, which reads: “Is as a sign on every man’s hand, that all men may know His doings.” (Job 37:7); and the Book of Proverbs: “In her right hand is the length of days, in her left, riches and honour.” (Proverbs 3:16)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.