Syria’s civilians are increasingly forgotten as humanitarian aid dries out

The millions of civilians in need of humanitarian aid in Syria are bracing themselves for dwindling international help this year, after the World Food Programme (WFP) has ended its mandate for the country as of 2024.

The Syrian government last week extended its approval for cross-border United Nations humanitarian aid to be delivered through a crossing with Turkey for another six months.

The mechanism is an attempt by Syrian President Bashar al-Assad government to enhance his legitimacy in the eyes of the international community since Russia, a main backer of Assad, blocked UN Security Council resolution to use the Bab al-Hawa crossing in July, forcing international partners to work with Damascus.

Previously, the UN had utilised four border crossings to provide relief to areas beyond the Syrian government's control, following a 2014 UN resolution sanctioned by the Security Council.

However, starting in 2017, Russia and China have gradually challenged this mandate, asserting that all aid should be routed through Damascus.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Since 2020, Russia and China have advocated for restricting aid deliveries to only one crossing, namely Bab al-Hawa. However, financial aid allocated to Syria has significantly dropped over recent years due to the prolonged crisis in the country, and more demands elsewhere, straining the financial capacities of aid organisations.

Last year, the WFP announced the closure of its food programme in Syria, supporting 5.6 million people, including those displaced in the country's northwest.

Simultaneously, USAID and the State Department are implementing significant reductions, of at least 30 percent, in US assistance for Syria, a move anticipated to be mirrored by European donors.

Why is the amount of aid decreasing?

In 2021, 1,000 aid trucks were entering Syria's north, but this number decreased to 445 last year - and the humanitarian situation is not getting better.

For instance, Geir O Pedersen, special envoy of the secretary-general for Syria, recently highlighted the challenges facing Syria, “including the lack of reliable access to drinking water, chronic fuel and electricity shortages, a cholera pandemic, the total collapse of basic social services, gender-based violence, malnutrition and psychological disorders among children.”

The main reason behind the scaling back of aid appears to be the reluctance of donors. Not only for residents of Syria’s north but also for Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon, the amount of aid is almost grinding to a halt.

In December last year, WFP stated that its budget was shrinking because of donor fatigue, the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and now Israel’s war on Gaza.

It also announced that it needed $593m for six months to maintain its operations properly but the amount it was able to spend was $2.8m for October.

“Aid to Syria is diminishing because attention is fading away. Violence has decreased, it’s a largely stalemated conflict, and Syria is old news by now,” Aron Lund, an expert on Syria, told Middle East Eye.

Lund also believes that the global economic situation, especially after the pandemic, has increased the pressure on funds allocated by wealthy western nations.

“We are now forgotten victims of a bloody war,” Uthman Saeb, a resident of Idlib province, told MEE in a phone conversation.

“We don’t have a proper house but have been living in a cottage for years. There is no job. We rely on a basket of food they [the UN aid agencies] bring us. Now, they say the basket will get smaller and smaller. How are we going to feed ourselves?”

Lund argues that the problem is not just about fewer donations but also the growing needs of Syrians due to worsening economic conditions in not only Syria but also in its surrounding countries like Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon.

The gradual loss of funding is believed to be resulting in substantial service gaps for Syria’s internally displaced refugees, but more importantly in intensifying certain vulnerabilities.

Increasing vulnerabilities: drugs and terror

Among these vulnerabilities are drugs and joining armed groups, including the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the Islamic State (IS), or pro-Iran and Russia-financed militias.

“The Syrian crisis has less attention from donors now as the world has focused on Ukraine, and now on Gaza. In every conversation, the donors say the same thing: 'We are exhausted with Syria'," an international non-governmental organisation (INGO) manager said, speaking on the condition of anonymity due to his organisation’s partnership with the UN.

'Aid to Syria is diminishing because attention is fading away. Violence has decreased, it’s a largely stalemated conflict, and Syria is old news by now'

- Aron Lund, Syria expert

However, the INGO manager warned of consequences such as the revitalisation of IS.

“Currently, people in Syria, especially in the northwest, don’t care about ideology or whatever. Daesh [an acronym for IS] is paying $100 per month, which is more than any amount a family could make. So, families tend to send their underage children to IS.”

“They are now even delivering brochures in coffeehouses,” Saeb said. “They take youth to the south where they are strong,” he added, possibly referring to Raqqa, a former IS stronghold.

“It’s not only Daesh but also the SDF, or the PYD (Democratic Union Party), whatever you call it. On the regime side, Iran- and Russia-backed militias lure youth. People just send their children.”

There have been recent reports stating that IS has gathered strength in the last few months and even been attempting to begin collecting taxes.

Etana, a group monitoring military activity in Syria, has also said that “the number of ISIS attacks continued trending upwards in recent months, with December witnessing a total of 12 armed attacks.”

Lund believes a place like Syria is a perfect hotspot for armed groups to recruit.

“There’s an endless supply of frustrated and desperate young men who know nothing except war. People can’t find jobs or envision a decent future,” Lund said, adding that “police and security services are brutal in all corners of Syria, but they’re also weak and dysfunctional, due to all-pervasive corruption, a shortage of resources, large areas that are basically lawless, and gaps in governance between the rival regimes.”

The danger is not only the revitalisation of IS or the intensification of armed conflict but it also comes from drugs.

“Another way to make money is drugs,” the INGO manager said.

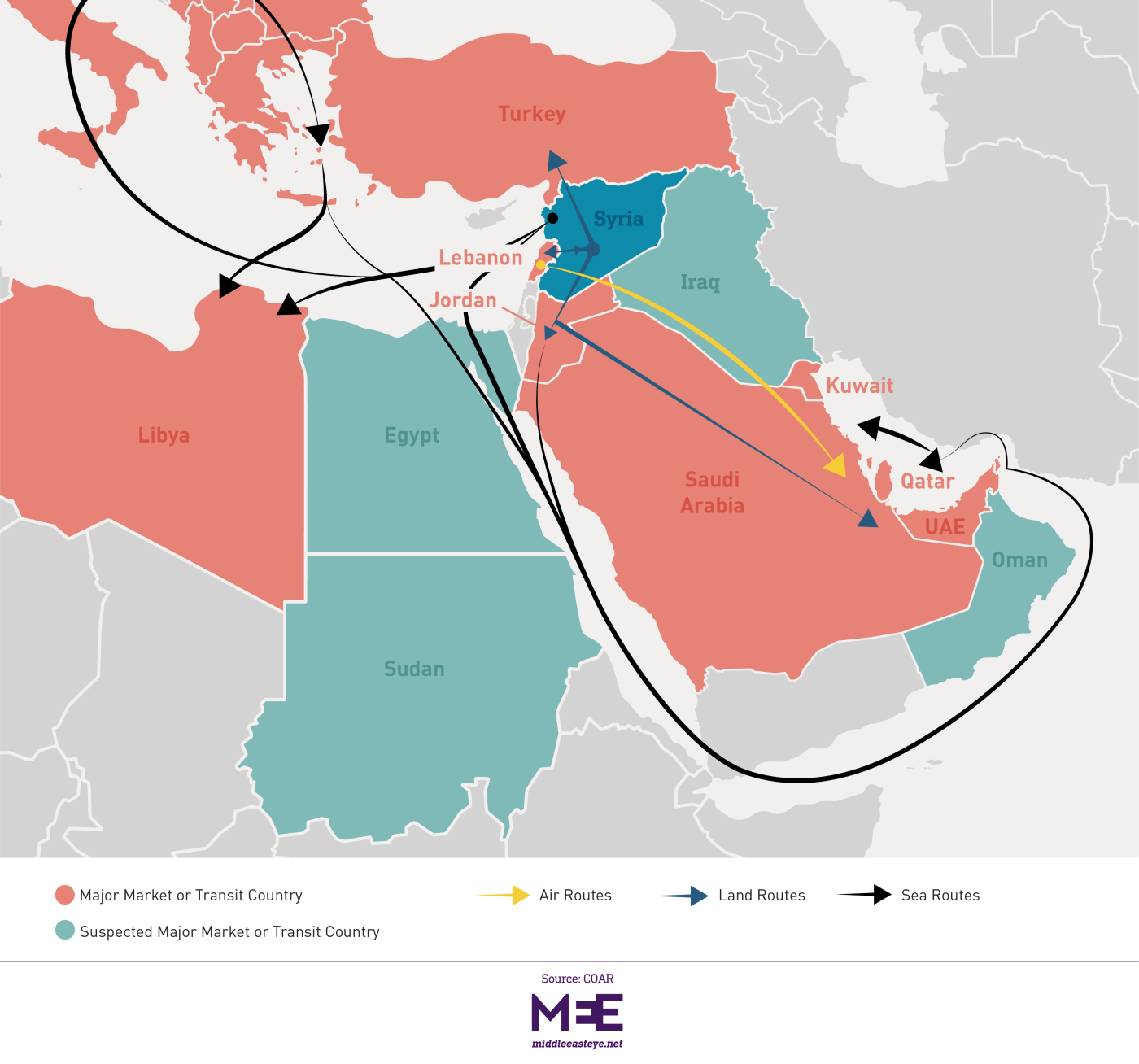

The Assad government is believed to be making billions of dollars through trafficking drugs to Western and Gulf countries. Eighty percent of Captagon, a highly addictive amphetamine drug, is produced in Syria, and its trade is estimated to be worth billions of dollars annually.

“We hear about the drug thing, but Hayat Tahrir al-Sham is strict on this kind of illicit things,” Saeb said, referring to the Islamist group that controls Idlib’s centre and its surrounding refugee camps.

“But the aid shortage is not a problem only for the rebel-held areas but also for the regime areas that are more exposed to the drug issue,” the INGO worker said.

Indeed, the drugs issue has strained Jordan's relations with the Syrian government. Jordan has recently launched several air strikes on Syrian villages, citing them as the production centres of drugs.

Increasing needs but decreasing aid

The worsening economic situation along with the decreased international aid is exposing Syrians to illicit activities more than ever.

'We are now forgotten victims of a bloody war'

- Uthman Saeb, Idlib resident

The Syrian government has recently removed subsidies, increased taxes and oil prices, which has led to rare protests last summer. Moreover, food prices have doubled in less than a year.

Ninety percent of Syria’s population live under the poverty line.

The UN estimates that the number of people in need of humanitarian assistance surpassed 15 million in 2023, a five percent rise in comparison with the previous year. This number is expected to rise to 16.7 million in 2024.

“At the end of this road lies social breakdown, renewed conflict, epidemics, and starvation,” Lund said.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.