Five stories that didn't happen in the Middle East over 2018

The United States opened an embassy in Jerusalem. Sanctions crashed the Iranian economy. Jamal Khashoggi was brutally murdered in a Saudi embassy. Yemen was further pushed to the brink of famine.

No one can say that 2018 was an uneventful year.

But the past 12 months have, however, passed without seeing a few moments that had been billed by politicians, the media and the military as being the biggest events to come in the Middle East.

Some of these stories’ failure to emerge has provided sweet relief for the region. Others tell a darker tale.

Middle East Eye takes a look at the biggest things not to happen in 2018.

Trump’s 'Deal of the Century'

Billed to be the crowning achievement of US President Donald Trump’s foreign policy, the “Deal of the Century” to finally bring peace to Israel and Palestine never emerged in 2018.

Don’t expect to see it any time this century, either.

Part of the problem, it appears, is that Trump’s deal doesn’t look much like a deal at all.

In June, Yossi Beilin, a former Israeli politician who was a pivotal figure in the Oslo peace process, told Middle East Eye that the terms were weighted heavily in favour of Israel and its prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu.

Back then Trump’s plan was scheduled to be announced after Ramadan. But it’s been more than six months since the holy month passed, with no sign of the deal on the horizon.

Demolition of Khan al-Ahmar

Khan al-Ahmar, a Bedouin village in the occupied West Bank, has been slated for demolition since an Israeli court waved away the residents’ last appeals on 5 September.

Activists, journalists and the village’s residents have been on high alert ever since, but so far the Israeli authorities have not moved the bulldozers in – despite often appearing on the brink of doing so.

Unfortunately for them, Khan al-Ahmar lies in an area of the West Bank that Israel seeks to develop, as it moves forward with plans to create sprawling illegal settlements around East Jerusalem.

Demolishing Khan al-Ahmar and forcing its 180 residents to a new location in the town of Abu Dis, apparently beside a landfill, would technically constitute a war crime.

With this in mind, the Palestinians have submitted the case to the International Criminal Court.

Yet Benjamin Netanyahu is unmoved, vowing "Khan al-Ahmar will be evacuated”.

Either way it’s a lose-lose situation for the village’s residents, with psychologists telling MEE in October that the uncertainty has left its children traumatised, worried about their future, homes, school and way of life.

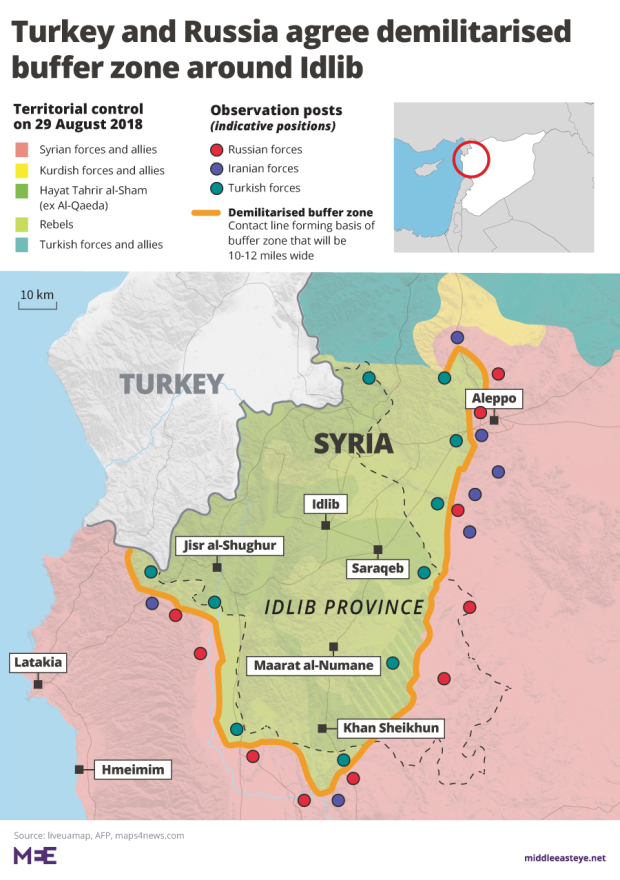

Syria’s Idlib offensive

2018 was a bleak year for the Syrian revolution, as two of the opposition’s last bastions – Daraa and Eastern Ghouta – fell to pro-government forces.

In September, all eyes fell on Idlib province in Syria’s north, the only territory still in rebel hands.

Forces loyal to President Bashar al-Assad began massing on the frontlines, Syrian and Russian warplanes bombed medical facilities, and aid workers warned that an assault on the enclave holding around 3 million people would cause a humanitarian crisis.

But just as the bloodbath appeared unavoidable, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin agreed to create a demilitarised zone and stave off a battle, which was met with jubilation by the hundreds of thousands of civilians trapped in Idlib.

“I hope the agreement works,” Ehad al-Haj, director of an organisation that trains women to develop professional skills in Idlib, told MEE.“So I can offer training programmes for education, instead of nursing and first aid.”

Israel strikes a deal with Hamas

On paper it looked like a perfect move for everybody.

Hamas would vow to halt any attacks from the Gaza Strip into Israel, while the Israelis would lift the crippling 11-year siege it has imposed on the coastal enclave.

Egypt-mediated talks between Hamas and Israel, two sworn enemies, were making “significant progress”, a source in the Palestinian group told MEE in August.

Not only was Israel reportedly offering to open all crossings between it and Gaza, but it also floated the idea of a sea passage from Gaza’s coast to Cyprus.

But as ever with the Middle East, nothing is simple.

Concerned that the negotiations could see Gaza drift further away from the Palestinian Authority-run West Bank, therefore undermining the possibility of a future Palestinian state comprised of both territories, Fatah intervened.

Fatah is said to have sent its own delegations to Egypt, and sources have said Hamas' rival successfully scuppered the deal.

In November, a botched Israeli raid sparked the most serious fighting since the 2014 war, leaving at least 15 Palestinians and one Israeli dead and closing the door on any imminent easing of Gaza’s siege.

Lebanon forms a government

In May, the Lebanese helped dispel the myth that its neighbour to the south is the only democracy in the Middle East, as Lebanon held the first parliamentary elections in nine years.

That was the easy part.

In the nearly eight months since, Lebanon’s politicians have in typical fashion failed to come together and agree on a national unity government that satisfactorily represents all parties and the confessions they profess to represent.

Such political impasses are common in the tiny Mediterranean country. Lebanon suffered a presidential vacuum for 29 months before its political parties agreed to elect President Michel Aoun in 2016.

Lebanese are feeling the brunt, and last week thousands took to Beirut’s streets in gilets jaunes-inspired protests against worsening living conditions.

Speaking in London earlier this month, Prime Minister-elect Saad Hariri said Lebanon was in “the last one hundred metres of forming a government”.

But as one Beirut-based journalist put it, “This would be true if it were a one hundred metre race."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.