Plagued: Misreading Camus in the age of Covid-19 and Black Lives Matter

Dark times call for great literature. At least, that’s what the world’s newspaper editors and literati would have us believe.

Since the coronavirus pandemic emerged this year as a global menace, seemingly every publication on the planet has run an article comparing the situation to Albert Camus’ 1947 novel The Plague, and recommending the book as a parable for our troubled times.

He consistently opposed Algerian independence in favour of half-measures aimed at softening the sting of colonial injustice, not eliminating it

Last month, Steve Coll took his turn in the pages of the New Yorker. Alongside praise for Camus’ resistance to the Nazi occupation of France, Coll describes the author as a model of lucid rationality in crisis: “That Camus, writing in the mid-nineteen-forties, could conjure with such clarity, during an epidemic, a political morality that advocates for factual reporting, medical science, and public-health regimens seems astonishing.”

In an age when conspiracy theories run rampant online, and the US president peddles pseudo-science and snake oil from the Oval Office, Coll is right to champion a model anchored in reason. But is there no higher bar towards which we should strive today? A critical factor omitted by Camus and many of his modern admirers suggests an answer.

Coll’s homage, and most others published in recent months, fail to consider the colonial context in which Camus was born and lived, and in which The Plague is set. Of those I found, only Algerian novelist Kamel Daoud (author of The Meursault Investigation, an acclaimed “sequel” to Camus’ The Stranger), writing in Le Point, and feminist philosopher Jacqueline Rose, in the London Review of Books, raise the problem of France’s 132-year project of settler-colonialism in Algeria.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Initiated under the guise of the "mission civilisatrice" (civilising mission), France pursued its colonial project with a brutality that revealed its perpetrators to be anything but civilised. Today, Algeria still struggles to move beyond that tragedy. Walk the streets of any Algerian city and you will cross boulevards renamed for martyrs of the country’s bloody independence war. Almost six decades after it abandoned that fight and ceded its Algerian colony, French authorities still drag their feet at calls for official apologies.

Many Algerians view that reluctance as merely a continuation of the French colonial policies that long sought to erase them and their ancestors - to render Algerians invisible in their own homeland.

Colonial mindset

In the late 1940s, Algerians outnumbered European settlers, known as pieds-noirs, by eight to one. Oran, the port in western Algeria where the novel is set, was known for its large European population, but even there at least one in three residents was native Algerian.

Nonetheless, they are almost entirely absent from The Plague. Among dozens of named characters in the novel, none is Algerian. We never hear from them and almost never even hear of them; one of the only mentions is a line about the death of an anonymous Arab on an Algiers beach, a cheap allusion to Camus’ earlier bestseller, The Stranger.

Perhaps we should not find this surprising; although he served as a writer in the resistance against Nazi occupation, Camus never managed to escape the colonial mindset into which he was born. He consistently opposed Algerian independence in favour of half-measures aimed at softening the sting of colonial injustice, not eliminating it. (It is for this reason that, despite Camus’ renown, independent Algeria has never embraced his legacy. No plaque graces his childhood home in Algiers.)

When it was released in the aftermath of World War Two, Camus’ novel was lauded as a poignant allegory for France’s resistance against Nazi occupation. Somehow, few readers detected the contradiction: France was lamenting its own occupation back home, while perpetrating another just across the Mediterranean in North Africa.

Shouldn’t the fact that his novel was set in Algeria have been an obvious clue? Had Camus himself not failed to make the same mental leap, one might wonder whether his novel wasn’t some grand satire lampooning colonialism.

Blind to injustices

Today, in a world turned upside-down by Covid-19, writers propose The Plague as a guide for readers anxious and adrift. But perhaps the book’s recent resurgence reveals literature’s limits, not its strengths.

How else could bibliophiles hail a novel as a parable of human decency (the theme Camus chose to highlight in the novel’s closing lines) - a metaphor for the triumph of good over evil - while simultaneously remaining blind to the injustice in which it is anchored?

Part of the answer may be that The Plague’s new promoters come from the ivory towers of French literature departments, not history departments. As one of Camus’ contemporaries, the talented Algerian writer and linguist Mouloud Mammeri, once said: “The past weighs with all its gravity upon the present, and it is upon the past that the future will be grafted.”

In viewing the novel merely as a literary work, uncoupled from its historical context, many today have missed the elephant in the room - despite years of scholarship criticising Camus’ erasure of native Algerians. His champions in the popular press have failed to pass these critiques along, instead delivering unqualified endorsements.

Profound inequalities

Is such fussing really necessary, though? Couldn’t we just read The Plague as a story of a pandemic, without considering colonialism? Even setting aside the moral implications, no - not if we want to defeat the disease.

To stop a contagion’s race through a society - be it our own, or Camus’ lightly fictionalised mid-century Algeria - we must consider what aspects of the contagion and what aspects of the host society are enabling its deadly spread.

Imagine Oran in the 1940s: in a crowded seaside metropolis, a plague would strike Algerians and Europeans alike. Combatting its spread in one group while neglecting the other would be fruitless. Besides the cost in Algerian lives, that approach would sustain a reservoir of contagion that would continually reinfect the European residents.

Camus' novel does reveal a lesson for us today, albeit one that most of its promoters appear to have missed: to save some, we must save all

Had they valued the lives of the native Algerians equally, the colonial authorities of the novel might have taken a more holistic approach to fighting the plague, likely extinguishing its spread sooner and with fewer casualties all around.

Viewed in this light, Camus’ novel does reveal a lesson for us today, albeit one that most of its promoters appear to have missed: to save some, we must save all. Just as Camus and his fellow colonists ignored the Algerians in their midst, what long-suffering underclass are we failing to recognise and care for today, in our own world?

In mere weeks, the Covid-19 pandemic has exposed profound inequalities between racial and ethnic groups, genders, classes and professions, and many other cleavages in societies worldwide (not to mention the vast gaps between nations). Awareness of these divisions is rising and, in some places, the inequalities are gaining newfound attention in public debate.

Building a 'new normal'

Some have called for building a “new normal” that would value low-wage and low-status workers, ensure better access to healthcare, better protect the vulnerable, correct our dangerous climate trajectory and right many other wrongs we have ignored for far too long.

They are right to do so. Deadly though it is, Covid-19 is not the imagined plague from Camus’ novel, nor is today’s world comparable to that of the 1940s. With our vast resources, improved scientific knowledge and global information architecture, we need not follow the model of that war-torn, disconnected and profoundly unjust age. There is little to celebrate in muddling through a pandemic while avoiding the honest self-reflection necessary to truly grow and improve.

Yet, in the novel’s closing pages, the surviving colonists do celebrate the plague’s disappearance - by singing and dancing in the streets, even as the injustices of colonialism persist. Armed with the benefit of hindsight, can we not do better today?

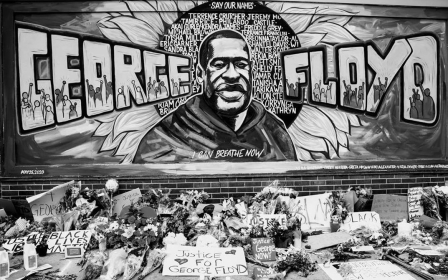

The eruption, in recent days, of protests and unrest in my native United States in response to police brutality against Black Americans suggests that that society, at least, is not doing better.

Like Camus and his fellow pieds-noirs, the US elite (myself included) have long ignored the pain of this underclass in their midst, neglecting their calls for reform, despite repeated appeals. Here, too, Camus’ story offers unintended but instructive lessons.

Tearing down systems of oppression

Seven years after The Plague was published, Algerians launched the revolution that would upend France’s colonial project. That decades of erasure by their colonial overlords provoked that uprising is evident; less obvious is how that same erasure also enabled the revolution’s success.

By wiping native Algerians from their own mental image of Algeria, French settlers rendered them invisible, allowing the Algerians to organise in secret. In her memoir Inside the Battle of Algiers, Algerian liberation heroine Zohra Drif highlights how, while the French made little effort to understand Algerian culture, the Algerians studied the French intimately.

“The deep ignorance and contempt in which the French held our people” enabled the Algerian fighters to launch attacks that drew international attention to their cause and changed the course of the war, she notes.

That war toppled the world that Camus and his fellow colonists knew, all thanks to their own blindness towards Algerians and their suffering. Today, Americans and others would be wise not to follow their path, and instead to emulate pieds-noirs such as Maurice Audin, Fernand Iveton and others who joined the Algerians in defending the cause of justice.

That is to say, to listen to Black Americans and others in pain; to work to understand their suffering; and to join them in reforming or tearing down systems of oppression. This doesn’t mean proclaiming that you “don’t see colour”; that’s just another form of blindness and erasure. Instead, start by saying aloud: “Black lives matter.” Then, roll up your sleeves and work to ensure that they really do.

Long before they became freedom fighters, Drif and an Algerian friend found themselves in a playground squabble with their pied-noir classmates over none other than Camus. In her memoir, she recounts how the French students promoted his milquetoast proposals for tweaking the colonial system. Drif and her friend spat back: “You literature students should pick a new favourite writer … Then you will understand that in truly historical moments, it is those who resist, the ‘extremists’, as you call them, who are right.”

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.