Sudan coup: Why talks on the country's future are failing

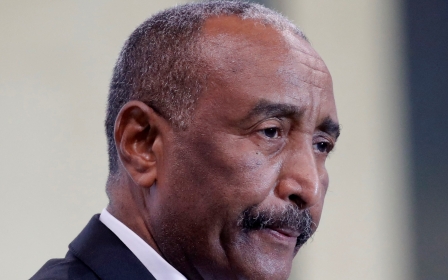

The dawn of 25 October will endure for a lifetime in the Sudanese collective memory. Citizens woke up to find bridges in Khartoum blocked and the capital isolated, with mobile and internet access disrupted. Uncertainty prevailed for hours, until army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan declared a state of emergency and the dissolution of Sudan’s government.

Protesters flooded the streets to denounce the coup, prompting a violent military crackdown. International organisations and human rights groups condemned Burhan’s seizure of power. The African Union suspended Sudan’s membership, and the US announced that $700m in aid would be withheld.

The question now is: How can Sudan bridge the gap between military and political leaders over the country's future direction?

Sudan’s future is now going to be reshaped rapidly. Having placed Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok under house arrest, Burhan justified the military takeover by asserting: “We exhausted nearly three years wasting much time and effort. If they were directed to productivity, our situation would have been different by now.” Backed by General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemeti, Burhan committed to holding elections in 2023.

The question now is: how can Sudan bridge the gap between military and political leaders over the country’s future direction? Negotiations cannot succeed unless both sides are given an equal opportunity to express their views. In this context, power dynamics are crucial - and such a process is impossible while Hamdok remains under house arrest.

Goodwill measures

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Preparing the ground for constructive dialogue is normally achieved through a number of goodwill measures. In the case of Sudan, the release of people detained in the coup’s aftermath must be front and centre. Dozens of politicians and teachers have been arrested in recent days, while Burhan also dissolved the boards of some state-owned companies.

The term “negotiations” might not even be accurate in Sudan’s current context, as it would appear the military has already decided on how the country’s governance structure should look, with talks centred mostly on the narrower question of who would be in charge. Yet, the country’s broader institutional framework needs to be at the forefront of any discussions, to ensure Sudan can build well-defined transitional institutions.

The overall objective of talks should be to sustain a sound democratic transition, but the military has already taken steps to unilaterally institute a new Sovereign Council, with Burhan as its head and Hemeti as his deputy. This jeopardises the entire negotiations process.

Burhan has also announced the reactivation of clauses he had suspended in Sudan’s power-sharing agreement, but with an amendment: the civilian-led Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) were excluded from the document, and Hamdok’s nomination withdrawn. The move effectively killed the dreams of Hamdok’s supporters to see him regain power.

Bracing for resistance

Not only due to his charismatic leadership, but also because he represents a wide range of democratic forces, Hamdok’s involvement in Sudan’s long-awaited transitional government aimed to ease tensions among the country’s various factions, while calming the anger of many civilians who are now taking to the streets to denounce the military coup.

While the events of 25 October marked a major setback for the country’s transition, the establishment of the new Sovereign Council may constitute a death blow. Good-faith negotiations are thus critically important.

A number of scenarios appear possible at this juncture. The military could unilaterally appoint a new prime minister to replace Hamdok and begin reshaping state institutions. But this would not lead to stability, as the FFC, a key democratic power with massive popular support, has been excluded from participating in the country’s government. The FFC and its supporters are now on standby for a potentially long and challenging period of resistance.

The only potential breakthrough would be if Burhan were to lift the state of emergency, release those detained on or after 25 October, and call for a constructive dialogue in which all parties have an equal voice. Unfortunately, given the ongoing military crackdown on dissenting voices, there is little imminent hope for such a resolution.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.