Abdulhamid II: An autocrat, reformer and the last stand of the Ottoman Empire

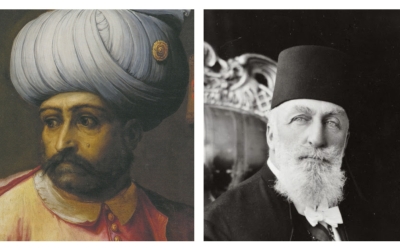

Abdulhamid II is one of the most controversial and divisive figures in modern Turkish history. His detractors call him the "kizil sultan" (the red sultan) after the blood they hold him responsible for shedding.

Supporters of the Ottoman sultan call him Ulu Hakan (the great Khan), for his assertive leadership style that echoed the methods of his ancestors.

However, many secularists believe he was an autocrat who held Turkey back from modernising alongside its European neighbours. They call him an Islamist because he focused his efforts on creating a pan-Islamic identity across the Ottoman Empire instead of one rooted in Turkish identity.

But despite these criticisms, there’s no escaping the fact that the Ottomans underwent a great transformation under Abdulhamid II.

Under his rule, new schools were established to train the Ottoman elite in western ways of thinking.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

At the same time, the sultan reinvented the institution of the caliphate in a bid to unite his Muslim subjects of various ethnicities under the umbrella of a multicultural Ottoman identity.

While remembered fondly by Islamic movements within Turkey and outside for his efforts to bring Muslims together, his project ultimately failed and those Turkish bureaucrats who came up through his schools eventually turned against him.

In 1908, Abdulhamid II was deposed in the Young Turk Revolution. After WWI, the Ottomans lost most of their empire and in 1924, the caliphate, the last remnant of Ottoman vestige, ceased to exist. Turkey would henceforth be a republic.

Early life and personality

Abdulhamid was born in 1842, an Ottoman prince (sehzade) and son of Sultan Abdulmecid I. As a child, he was educated in the Arabic, Persian and French languages and taught western music by Italian tutors.

As a member of the Ottoman royal family, he was born into a life of entitlement but was not expected to take up a significant role within the empire, due to his lack of seniority amongst his brothers.

Abdulhamid therefore took on more worldly interests, specialising in agriculture, mining, carpentry and finance. At one point he even considered becoming a broker in Istanbul’s stock exchange.

Described by historians as an introvert with no real interest in governance, Abdulhamid spent his time indulging in his passions, such as his love of western opera, instead of involving himself in palace intrigues.

With the death of his father Abdulmecid in 1861, Abdulhamid’s paternal uncle Abdulaziz took the throne and it seems that he noticed signs of political acumen in the young man.

The new Ottoman sultan included Abdulhamid in his entourage and even brought him along during state visits to Europe and Egypt.

By 1876, however, the knives were out for Abdulaziz, as the empire fell into internal turmoil.

Famine had taken root in parts of the empire, Christian minorities were in rebellion and reformist factions, such as the Young Ottomans, were plotting his removal and replacement with a prince more sympathetic to their goal of creating a constitutional monarchy.

Abdulaziz was replaced with his nephew, Abdulhamid’s half brother, who would become Murad V.

Within days of Abdulaziz's removal, he died in mysterious circumstances. Many believe he was murdered.

But Murad’s reign was short-lived, as mental and physical health issues prevented him from ruling effectively.

That cleared the way for Abdulhamid to take the throne in September of that same year.

Early rule

Taking power during a period of unrest within the empire meant the stage was set for a series of significant upheavals.

As tensions brewed internally, the Russian Army was preparing to invade Ottoman territory, as were the Bulgarians and Greeks.

Compounding these challenges, the empire found itself ensnared in debt owed to European powers, further straining its resources.

By emphasising his role as leader of Muslims, inside the empire and outside of it, the sultan made it a religious duty for Muslims to obey him.

Against this backdrop, calls for a constitutional monarchy like that in Great Britain grew louder.

Abdulhamid II initially made concessions to the reformists, pledging to establish a parliament and usher in a constitutional monarchy.

Before the year had ended, Abdulhamid had enacted the empire's inaugural constitution, known as Kanun-i Esasi, and convened a parliament.

The inaugural Turkish parliament comprised 115 deputies and 26 senators, reflecting the diversity of the Ottoman Empire with 69 Muslim deputies and 46 non-Muslims.

However, the initial hopes for unity within the legislative body swiftly dissipated as ethnic factions pursued their respective agendas.

Meanwhile, the Russians grew closer. Following an Ottoman defeat, Russian forces had advanced to Ayastefanos, which was a mere 20 kilometres from the Ottoman palaces of Istanbul.

Confronted with these many crises, Abdulhamid II turned to more autocratic methods of rule.

By March 1877, parliament was dismissed and, the following year, the new constitution was suspended.

Those who opposed the sultan faced exile and power was maintained through an extensive internal network of spies.

The Ottoman sultan also manoeuvred to fortify his rule using an archaic title that few Ottoman leaders before him had emphasised during their rule.

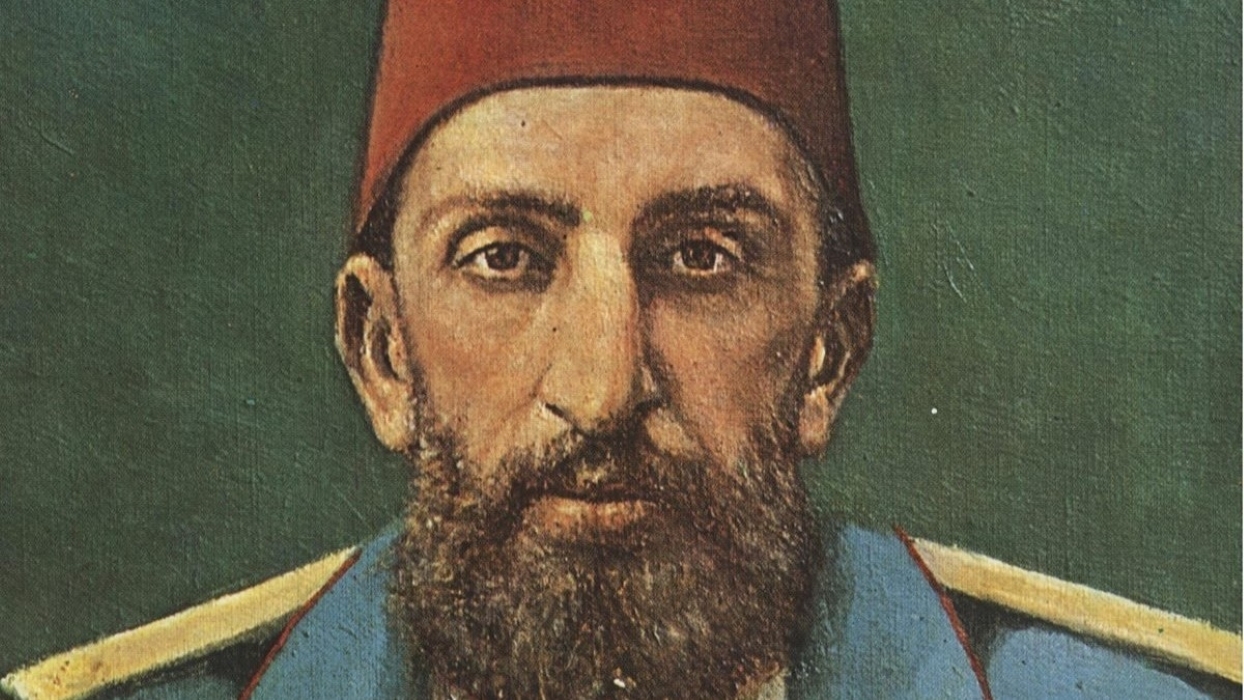

Abdulhamid proclaimed himself the Caliph of all Muslims, leveraging religious authority to bolster his political legitimacy.

The role was included in the constitution from its inception and underscored Abdulhamid’s intent to wield the caliphate as a potent instrument of governance.

While Ottoman sultans had traditionally held the title of caliph since 1517, Abdulhamid II's use of the title marked a pivotal moment when the caliphate assumed unprecedented political significance.

By emphasising his role as leader of Muslims - inside the empire and outside of it - the sultan made it a religious duty for Muslims to obey him.

The autocrat reformist

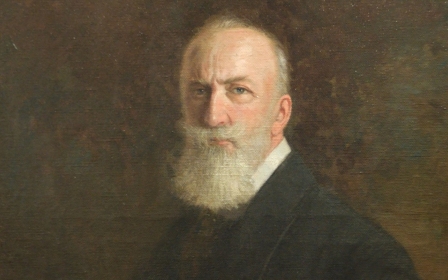

Despite Abdulhamid's stringent measures against dissent, including the exile of dissidents and the censorship of publications, his reign was characterised by a dual commitment to reform and preservation of the empire.

Contrary to modern-day perceptions, Abdulhamid recognised the need for sweeping change to ensure the survival of the Ottomans.

Under his leadership, the empire underwent a comprehensive modernisation drive, marked by the establishment of higher education institutions specialising in fields such as engineering, law, education, and fine arts.

This initiative aimed to cultivate a generation of skilled professionals and civil servants equipped to navigate the challenges of a rapidly modernising world.

Additionally, Abdulhamid championed the promotion of western languages as part of a broader effort to embrace modernity.

He also oversaw the inauguration of the first schools for girls and a substantial expansion of primary and secondary education into rural areas.

At the same time, he spearheaded initiatives to enrich the cultural and intellectual landscape of the empire, founding institutions like the Museum of Antiquities, the Military Museum, Bayezid Library, and Yildiz Archive and Library.

However the impact of Abdulhamid's reign extended beyond education and culture and he also pushed forward infrastructural advancements.

For example, he oversaw the implementation of horse-drawn and electric tram systems, the establishment of docks in various cities, and the extension of telegraph lines to regions as distant as Hejaz and Basra.

Particularly noteworthy was the ambitious construction of the Hejaz Railway, which connected Istanbul to Mecca and was a testament to Abdulhamid's vision of fostering connectivity within his territories.

By 1914, the line led up to the Muslim holy city of Medina, before the First World War put a stop to its advancement.

Abdulhamid also made significant strides forward in ensuring law and order, underscored by the enactment of criminal and commercial procedure laws and the establishment of the chief public prosecutor's office in courts.

The restructuring of the police force along western lines and the establishment of a retirement fund for civil servants further modernised governance structures.

Abdulhamid's reforms moved the empire into a new era, aligning its institutions and practices with western standards while safeguarding its legacy.

The Caliph

From the early years of his rule, Abdulhamid II confronted several challenges as the Ottoman empire grappled with external pressures and internal dissent.

Forced to pay substantial war reparations to Russia and facing territorial encroachments by European powers, the empire found itself embroiled in a series of disputes and uprisings.

Internally, nationalist movements were taking root amongst both Muslim and non-Muslim subjects.

Against this tumultuous backdrop, Abdulhamid II leveraged his position as the caliph to assert the empire's religious and political authority.

Recognising the potential for unrest amongst Arab populations, Abdulhamid II embarked on a campaign to cultivate closer ties with Arab communities, granting them greater representation within the administration of the state and extending honours to prominent Arab figures.

Beyond the empire's borders, Abdulhamid II's caliphate policy extended its reach, with Indian Muslims seeking his intervention in their affairs with Great Britain, and Queen Victoria soliciting his assistance in dispatching religious scholars to South Africa.

Initiatives to strengthen ties with Muslims in Central Asia, Japan, and beyond underscored Abdulhamid II's commitment to fostering a sense of unity and solidarity amongst global Muslim communities.

Abdulhamid II's efforts to consolidate his authority as caliph were also evident in his support for educational and religious initiatives, including the establishment of schools, madrasas, and mosques, as well as the dissemination of Islamic literature and the financing of mosque construction across various regions.

Despite his reformist zeal and diplomatic acumen, Abdulhamid II's reign ultimately succumbed to internal pressures, culminating in his deposition in 1909 by a younger generation of reform-minded individuals.

Exiled to Salonica and later returned to Istanbul, Abdulhamid II witnessed the unravelling of the Empire he had governed for over three decades until he died in 1918.

Ultimately, Abdulhamid’s demise can be described using the old adage of “doing too little, too late”.

The Ottoman empire was not only contending with its internal weaknesses, but also a global revolutionary moment, in which subjects held their leaders to account in ways they had never done before.

Military defeats, and persistent internal turmoil, meant that even with his vast reform programme, Abdulhamid could not placate the forces out to remove him from office.

His name, however, has undergone a rebranding in recent years under Turkey’s AK Party, led by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Under the AK Party, Turkey has sought to reconcile its Ottoman past with its new position as a republic.

Given that change, Abdulhamid provides a loose model for reconciling the challenges of modernity with traditional Turkish identity.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.