Dance in the Middle East: Moving forward, step by step

Contemporary dance emerged in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s before spreading to Europe and then the rest of the world.

In the Middle East its development has been slower, flourishing from the 1990s onwards thanks to a handful of artists.

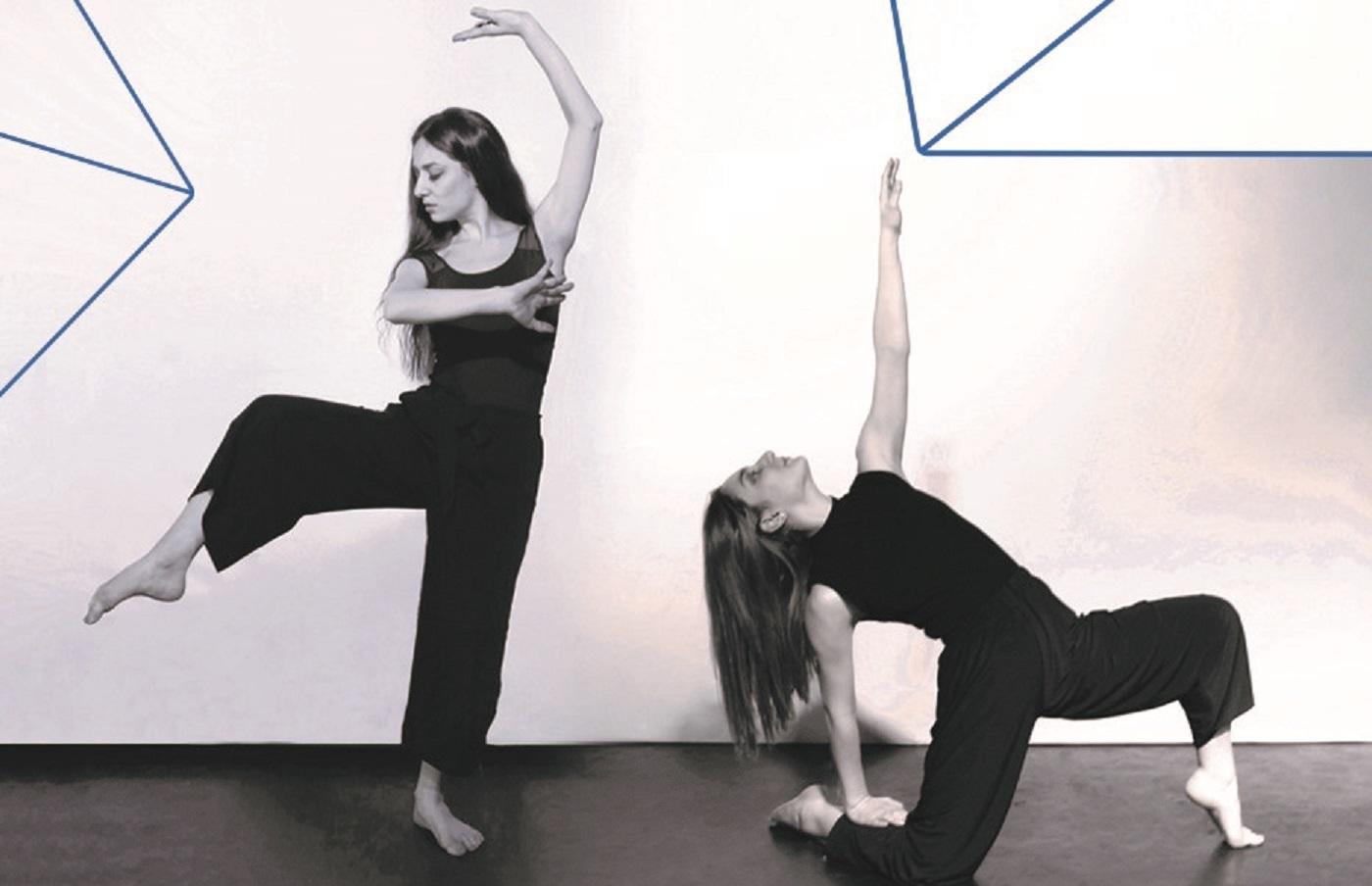

Contemporary dance, with its non-traditional approach, is often regarded as inaccessible, even elitist. But it's better to regard it as a hybrid artform, as exemplified in how personalities including Merce Cunningham in the United States and Pina Bausch in Germany combine dance, theatre and the visual arts. Further inspiration has come from traditional and even folkloric dance.

Despite the cultural diversity of the Middle East, dancers across the region are beset by common issues, including lack of space, cultural apathy and social conflict. Many understandably leave for Europe or elsewhere, frustrated at the lack of opportunity.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

But others stay and persist: the growth of contemporary dance in the Middle East is as much down to their determination to find a way forward as it is to their artistic endeavours.

Lebanon: The need to build networks

Contemporary dance pioneer Omar Rajeh, considered the founder of the Lebanese scene, trained first in theatre and dance in Beirut and then in the UK. But he was shocked on his return to Lebanon in 2002.

"Even the term 'contemporary dance' was unheard of at the time," he says. "There were no real spaces dedicated to dance. When I started performing my work, the audience was enthusiastic. I realised we needed to think bigger, to envision a national network for dance in Lebanon.”

His initial step was to found Maqamat, Lebanon's first contemporary dance company. Then, in 2004, he established the Beirut International Platform of Dance (BIPOD), an annual event promoting the works of emerging and established Lebanese and Arab choreographers.

"The network focuses on developing contemporary dance in Lebanon by presenting works for emerging artists here in Lebanon," Rajeh says, "in collaboration with a network of regional partners."

'I realised we needed to think bigger, to envision a national network for dance in Lebanon'

- Omar Rajeh, dance pioneer

Together with Khaled Elayyan, the choreographer and artistic director of the Sareyyet Ramallah Foundation (which promotes culture in the West Bank), Rajeh co-founded Masahat Dance Network, a regional contemporary dance network. Aside from Maqamat and Sareyyet Ramallah, its partners include The National Centre for Culture & Arts in Jordan, and – until the outbreak of war - the Tanween Company For Theatre & Dance in Syria.

"We want to help international companies performing in Lebanon to perform in Jordan and Palestine as well." For that reason, he adds, BIPOD and the festivals in Ramallah (RCDF) and Amman (ACDF) are all scheduled at the same time of year.

Other projects include Moultaqa Leymoun, an international platform showcasing Lebanese and Arab dancers; and Takween, which organises conferences, workshops and dance classes.

Last March the lack of space for dancers prompted Rajeh to open Citerne Beirut, a venue providing local artists with a 1,000 square-metre space devoted to dance practice, creation and performance.

"It is a space for encounters and dance performances," Rajeh says. "But the design of the main hall allows it to be rented out for corporate events as well. This will enable us to generate revenue to finance our productions and artist projects."

Palestine: International festivals build buzz

The seed for contemporary dance in Palestine was first planted by choreographer Khaled Elayyan, who in 2006 invited dancers from Europe to take part in a contemporary dance workshop and to hold a performance.

"There was nothing but traditional dance at the time," says Hala Swiedan, co-director of the Ramallah Contemporary Dance Festival (RCDF), "and he wanted to do something new. That's where we got the idea for the festival.”

A year later Elayyan teamed up with Rajeh and the Masahat Dance Network to create the first contemporary dance festival in Palestine. The festival's 14th edition, which took place in Ramallah and East Jerusalem in April 2019, featured 19 performers and 15 dance companies, three of which were Palestinian.

Such events are rare in Palestine – but contemporary dance is gradually taking root.

"We are seeing the festival grow and expand year after year, in terms of both dancer and audience numbers," says Swiedan.

For the first time this year, the festival also organised the Palestinian Dance Forum, aiming to provide a space for Palestinian dancers to present their thoughts and works, and to foster cooperation between Arab and international festivals.

Jordan: State needs to give more support

Mustafa al-Shalabi is a young dancer in Jordan. But his choice of vocation has left him estranged from his father. "My father sees contemporary dance as a disgraceful way of life," he says. "He has a hard time understanding what I do because he sees it as a shameful activity. It doesn’t correspond to his vision of masculinity."

Like elsewhere in the Middle East, contemporary dance in Jordan has had problems being accepted by the rest of society, who regard it as neither an artform nor a profession.

"Dance still has a hard time finding acceptance in Jordan where it is misunderstood by the most conservative members of society," says Rania Kamhawi, a dancer and festival director. "Despite there being so many talented dancers in the country, it is still not considered a profession. So, most dancers end up with full-time jobs and only train in their spare time, instead of the opposite."

Most dancers in Jordan are freelancers holding down day jobs, work on their own and have very few resources.

Shireen Talhouni is a freelance contemporary dancer who has held workshops at the Institut Français d'Amman.

"As a choreographer, too, it was complicated," she says of her return to Amman in 2013. "I couldn't find dancers to work with. In England, it was easy to find people free to work during the day.

"In Jordan, dancers often have another job on the side. The government doesn't support culture in Jordan the way it does in Europe. When it does, traditional artforms are preferred over contemporary dance. There are only two national theatres, and they are extremely difficult to book if you are not affiliated with an institution."

Festivals are usually organised by dancers who tend to focus on promoting their own creations. The result: artists are working against each other

Another issue, she says, is that festivals are usually organised by dancers who tend to focus on promoting their own creations.

"It’s different in Europe. There are producers on one hand, and artists on the other. The monopoly here has slowed the development of contemporary dance in the country because artists are working against each other and not with each other."

There are signs of hope. Kamhawi plays a part in organising the Amman Contemporary Dance Festival, held each year by the National Center for Culture and Arts (NCCA) of King Hussein Foundation. It's the country's only contemporary dance event to date.

"Having prominent international companies participate allowed us to showcase contemporary dance and raise appreciation among audiences," says Kamhawi.

In April 2019, the festival hosted eight local and international companies and attracted more than 1,000 participants, a resounding success despite the fact that there are still very few schools of contemporary dance in Jordan. The MISK Dance Company, founded by Kamhawi and supported by NCCA, is the only national company producing contemporary dance.

Egypt: Finding where to learn and train

Karima Mansour, a dancer and choreographer, best embodies the spirit of contemporary dance in the Middle East's most populous nation. After training at the Contemporary Dance School in London, Mansour returned to Cairo in 1999 and came to the same conclusion as many other dancers from the region: where is the space to rehearse and perform?

"Twenty years ago, there was nothing, only the Cairo Opera House and the Institute of Ballet,” Mansour recalls. “But they were classical dance companies, and you had to integrate them at a very young age. There were no studios for taking classes and training.”

Sarah Gabr Helmy, an Egyptian contemporary dancer who began her career in ballet at the Cairo National Opera agrees: "I began taking workshops at the Cairo Centre for Contemporary Dance, and I was instantly won over. I wanted to learn more but I had to travel abroad to study new approaches and take part in workshops."

In 2017, Helmy joined Takween in Lebanon, an intensive three-month contemporary dance programme organised by Rajeh and Maqamat Dance Theatre.

"In Egypt today there is only a single school and, to me, that's not enough. More spaces are needed so we can show our work and get more exposure. We also need a platform where artists can perform and meet because far too many dancers are still working alone."

'We also need a platform where artists can perform and meet because far too many dancers are still working alone'

- Sarah Gabr Helmy, dancer

In 1999 Mansour founded MAAT for Contemporary Dance, the first independent dance company in Egypt. It was followed in 2012 by the Cairo Contemporary Dance Centre, the only institution dedicated to contemporary dance in Egypt that also offered professional training.

Since then, Mansour has created 17 full choreographic works that are still performed internationally. She is also a teacher: in 2014 she launched The Platform, an intensive training three-year programme for young dancers who work together in the same group, six hours a day, five days a week. The classes are open to all and combine yoga, pilates, martial arts and anatomy among others. A first generation has already graduated, with a second generation in training.

"The idea is to give students a platform, a stage where they can train, experiment and perform,” she says.

"I am proud of what we've done because these are real Egyptian artists who have trained here and are figures on the emerging scene. We are building an ecosystem of contemporary dance in Egypt that we hope to disseminate at home and abroad."

Syria: On the road, fleeing war

Contemporary dance in the Middle East is often caught up in the region's political upheaval – and nowhere has this been more true than in Syria.

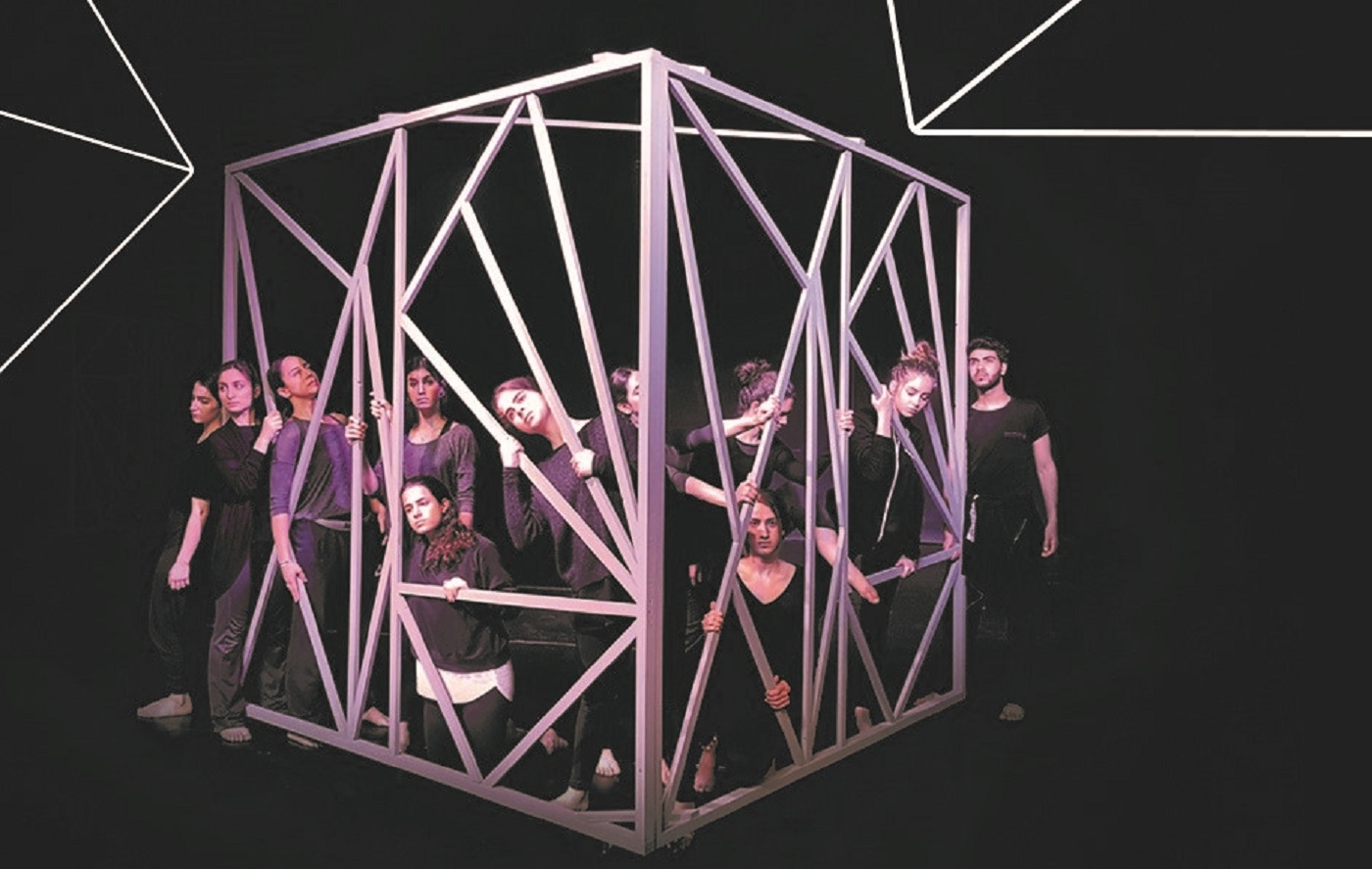

The Sima Dance Company was established in Damascus in 2003 with a handful of dancers from the city's university by Alaa Krimed, a choreographer and dancer, and Lana Fahmi, lead artist and his wife.

"At the time, there was only traditional dance [dabkeh] or classical dance in theatres," Fahmi says. "Alaa wanted to challenge the conventions of traditional dance, to take a more expressive and experimental approach."

Within a decade Sima had progressed to larger venues, national theatres and the opera house: audiences was enthusiastic about this "new" form of dance, Fahmi says, but funding was limited.

War forced the company – which, during its time in Syria had trained more than 70 dancers - to flee to Lebanon.

There, Sima played to appreciative audiences and was even asked to perform in the TV show Arabs Got Talent, which it won.

But former residents of Syria are discouraged by the Lebanese authorities from staying long-term in the country - within two years of national fame, Sima moved on again, this time to the Gulf.

Dubai: A new home

Members of Sima found that Dubai could be an artistic desert when it comes to contemporary dance.

"I was pretty depressed at first, because four years ago in Dubai it was extremely difficult to find studios to train at," Fahmi says. "Contemporary dance was non-existent. The only classes available were classical, hip hop or popular dance. The same thing for performances – only large-scale ballet productions at the opera house."

Through hard work and determination, the company reinvented itself and began regularly touring the UAE as invitations to perform in Dubai, Sharjah and Abu Dhabi began to build up. Fahmi says: "The public was always very enthusiastic. We always danced to a full house."

The company now has its own space on Alserkal Avenue, in the industrial district of al-Quoz, the artistic and cultural hub of Dubai, working with more than 25 dancers of diverse nationalities and backgrounds.

But funds are hard to come by: much remains to be done to promote contemporary dance in Gulf states, where independent and alternative artforms are still in their infancy. For companies like Sima, survival and growth means working twice as hard.

"There are the dancers' salaries and the costumes, not to mention the cost of renting performance spaces. And venues are very expensive in Dubai. We are often invited to perform at government events like National Day, and the earnings are re-invested into our space and our creations.

"We are self-financed, but it is still difficult to get people to understand production costs."

This feature is based on a piece which has been translated from French and originally appeared on Middle East Eye's French site.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.