How Turkish TV, Bollywood and K-pop spell the end for the American century

It was the century of blue jeans, Coca-Cola and Madonna. America was the barometer of cool. Where we sat in relation to its impulses, determined our proximity to modernity.

But it’s no longer the 20th century. The world has changed. American prestige has been replaced by Donald Trump. Africa is awash with zombie flicks from Nigeria or soapies from South Africa. The Asia Pacific region is seeing Indonesian cinema like never before.

In an increasingly multipolar world, with multiple actors pushing multiple agendas, the idea of American culture as the arbiter of our cultural universe is over. And in her new book, New Kings of the World: Dispatches from Bollywood, Dizi and K-Pop, novelist and journalist Fatima Bhutto details the "new" cultural phenomena rising from the east, and sweeping the globe.

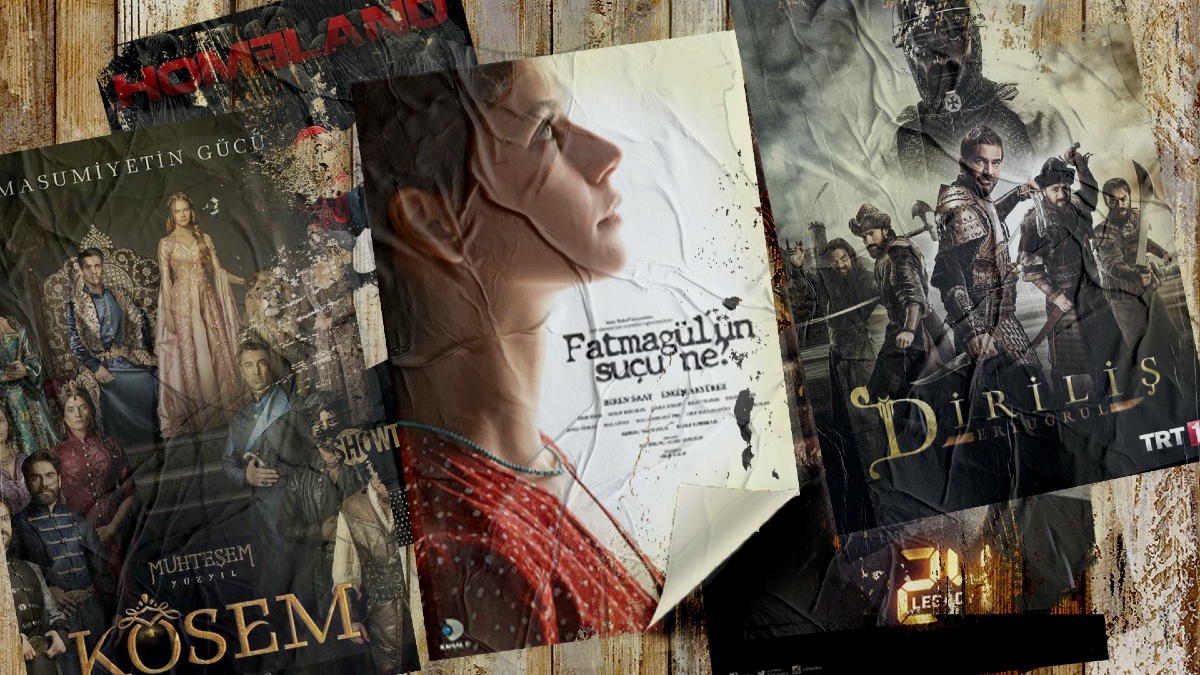

Hollywood may not yet be dead, but Turkish shows - popularly known as Dizi - Bollywood or Hindi popular cinema, and South Korean pop music, known affectionately as K-Pop, are at the forefront of challenging the mystique of American soft power, Bhutto writes in three essays that make up the book.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“To be American is no longer to belong to a vaunted, cultural elite,” she writes in her book, written as a light but thoughtful introduction to the new cultural motifs of our time.

Bhutto spends most of the book on India and Bollywood, including a profile on "the King of Bollywood", Shah Rukh Khan.

Bollywood has held a global audience for decades, starting with the former Soviet Union and North Africa as well as in the Middle East. In the 1950s, Bhutto notes, Lebanese businessmen living in Nigeria were importing Bollywood films into the country.

It is her second essay, on the global rise of Turkish television series, that is especially captivating and understated.

Those Turkish Dizi series have come a long way since the 1980s. Though they also adopt a slower form of storytelling, their emphasis on music, the visual and diverse modes of storytelling sets them apart from soaps and telenovelas. Each episode is also, in its own right (two hours long and with a vast production scale) an epic.

Dizi hits 'perfect balance'

As the world’s second largest producer of television shows in the world, Dizi audiences span more than 100 countries, from South America, the Middle East and the Asian subcontinent, with translations available in Spanish, Farsi, Arabic and Italian. Not so much in the English-speaking world.

“Turkish television shows blazed through the subcontinent and far beyond because their heroes were modern, but not westernised [and] propelled purely by the righteous power of values,” Bhutto writes.

'Turkish historical drama were not about wars in the Muslim lands like Homeland, or fiery sagas warning against unwashed villainous Muslim invaders: Here Muslims were kings'

- Fatima Bhutto

She says it is precisely Dizis’ ability to portray “modern life” without mimicking westernisation or American values that sets them apart. “They had achieved the perfect balance between secular modernity and middle-class conservatism,” she says.

The shows rarely depict women in the hijab, or the headscarf, which many women in Turkey wear, exemplifying the cultural tensions, even as they navigate age-old plots of love across class lines, estranged lovers and charismatic underdogs.

Moreover, the genre’s dexterity to be synonymous with human and societal issues in Turkey, sparking conversations about religion, nationalism, gender, violence and Ottoman history, has brought with it a universal appeal.

And there are reasons for that. Whereas American television can often revolve around individuals and offer a peek into loneliness, or obsessions with work, wealth and power as paragons of city life, Bhutto argues that Turkish Dizi “powered narratives that put values and principles in battle against the emotional and spiritual corruption of the modern world”.

“Turkish historical drama were not about wars in the Muslim lands like Homeland, or fiery sagas warning against unwashed villainous Muslim invaders: Here Muslims were kings,” Bhutto writes.

There is Fatmagul’un Sucu Ne? (What’s Fatmagul’s fault?), whose lead character bravely pursues justice after suffering gang rape at the hands of wealthy frat-boys. Magnificent Century told the story of a sultan’s love affair with a concubine, but was really about her “journey from slavery to becoming the queen of an empire”.

Likewise, where American television shows push the boundaries on questions of love or sexuality and take audiences to futuristic or dystopian neverlands, Turkish shows, Bhutto argues, are more relatable, or proffer a version of life audiences would love to lead.

She observes that audiences in Latin America have grown so tired of drug-related shows and highly charged sexual content from their North American neighbours, Dizis have become a staple of family viewing. Prior to Turkish shows running riot in the Middle East, including stealing attention away from the month of Ramadan (the fasting and religious obligations as well as the specially produced Arabic soap operas) or "causing" divorces, Mexican and Brazilian telenovelas were screened in places like Lebanon.

But more than television, they have also become immense and unnerving tools of Turkish soft power. And the scepticism of Turkish imperial ambitions is a recurring theme. One Lebanese voiceover artist tells Bhutto that the production values are so high, that Arabs, who might be ordinarily stiff to Ottoman history, allow themselves to be fooled into believing the stories and themes as their own.

The success of these shows in presenting an image of Turkey has also invited state scrutiny over subject matter and representations of the country. Every channel also carries a show venerating the state’s constant fight against enemies and traitors - inside and beyond.

Indeed, the Turkish state has made “direct and indirect impositions on the Turkish television industry from time to time due to concerns about the image of Turkey represented in these TV series,” Ece Algan, from the Institute for Media and Creative Industries at Loughborough University in London, wrote in the Heritage Turkey journal in 2018.

The Saudi blockade on Qatar (in which Turkey resolved to help Qatar) resulted in Dizi being taken off screens in parts of the Middle East. But this hasn’t stopped tourists from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates from flocking to Istanbul.

Bhutto’s analysis of Dizi suffers a little for having been written mostly before the resounding success of Dirilis Ertugrul (Resurrection Ertugrul), the story of the son of Suleyman Shah and the father of Osman, the founder of the Ottoman Empire, that captured the imagination of many Muslims, and non-Muslims across the globe.

Ertugrul defies many of the conventions ascribed to the success of Dizi, with its tight adherence to and expression of Islamic values, including prayer, dress and philosophy, and for its willingness to depict war in shades of chivalry.

But the success of Ertugrul is indicative of Dizi being a “genre in progress”.

If Dizi firmly put Turkey on the modern cultural map, as a rearguard act to American soft power, Ertugrul ran riot among Muslims in the Middle East and in the English-speaking world as a symbol of justice and leadership. It also provided fodder for Recep Tayyip Erdogan to stir the neo-Ottoman imagination as a project of statecraft.

In her narration of a vast cultural movement sweeping through the globe, Bhutto’s keen eye for the odd and diffident makes her chapters on Dizi and Bollywood a treasure trove of secrets. She makes a series of important observations on the narrative junket proffered by Bollywood’s elite, led by arguably its biggest star, Shah Rukh Khan.

About his role in Bollywood’s expansion in the 1990s, she describes the films as a “strange marriage between the Indian neoliberal fantasy of money, power and [...] a distinctly cultural assertiveness”.

Bollywood is a shadow of its former self; intensely jingoistic, racy and pornographic in its depiction of wealth and excess. Though it remains popular as an alternative to American mainstream cinema, it has become increasingly indistinguishable from its American counterparts.

On K-Pop, Bhutto underlines the history of the pop music genre as an industry borne almost entirely out of an economic impulse to expand Korea’s exports. She describes K-Pop as “a perfect storm of colonial history, Americanised culture, and neoliberalism”.

In a theme that is repeated throughout the book, the new Kings of the World - as distinct as they might be - are also in many ways vaguely different versions of American culture; repurposed, repackaged, with a set of local values that are carefully manicured for the global market. Where Bollywood and K-Pop commodify good old Asian values into bubble gum limericks, Dizi is just enough of both worlds to make its mark.

New Kings of the World: Dispatches from Bollywood, Dizi and K-Pop, by Fatima Bhutto is available from Columbia Global Reports, an imprint of Columbia University

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.