‘Go ask Jahangiri’: How Iranian politician went from rising star to punchline

TEHRAN - In the heat of last year’s presidential elections, Eshagh Jahangiri’s star was rising.

The 60-year-old Iranian politician from Kerman – the same region that has produced General Qassem Soleimani and former president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani – blew his competitors out of the water during televised debates.

'My dollar is so expensive,' one Iranian says to another. 'You need a cheap dollar?” says his friend. “Go ask Jahangiri'

- Popular Iranian joke

“There’s a movement called the reformist movement and you’ve deprived them of all rights and now you are saying that they shouldn’t even have a candidate,” he told the crowd.

Iranians, he said, should not forget what happened during Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s time in office. “They confined everyone to their houses. They earned $700bn, they took it, they spent it and they left nothing, just unemployment.”

During the 1979 revolution, Jahangiri, then in his early 20s and active in political groups, was wounded by the forces protecting the Shah.

After studying industrial management at university, he went on to become the governor general of Isfahan province, and then served as minister of industries and mines from 1997 to 2005, under President Mohammad Khatami.

Since 2013, he had twice served in the shadow of moderate president, Hassan Rouhani, as his first vice-president, the most prominent reformist in the government, but also a behind-the-scenes technocrat of sorts. Suddenly, in the run up to the 2017 elections, Jahangiri captivated the country’s attention.

There were suspicions that he was running only to help Rouhani amid concerns he would be disqualified by the Guardian Council from running, and that eventually, he would pull out before election day - which turned out to be exactly what he did, three days before the vote.

Still for a moment, Jahangiri was the talk of the town – some supporters suggested he might be better than Rouhani, and if not in 2017, he was a distinct possibility as his successor in 2021.

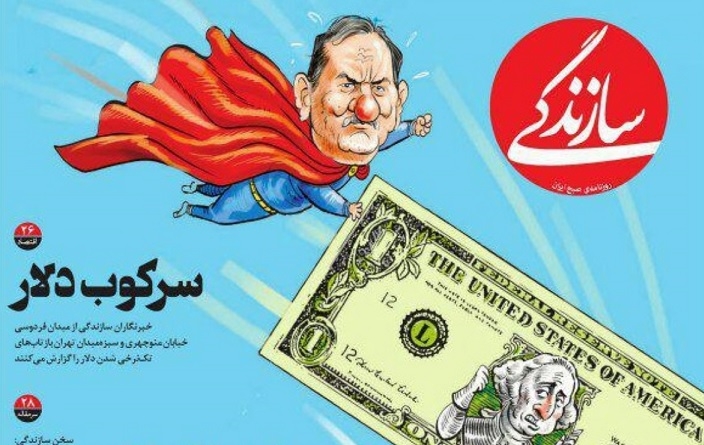

Fast forward a year, Jahangiri's star has fallen as dramatically as the Iranian rial, and he has become the butt of political jokes. “My dollar is so expensive,” one Iranian says to another, so one joke goes. “You need a cheap dollar?” says his friend. “Go ask Jahangiri.”

Wanted: Strong candidate

Following the 2009 presidential elections, there was widespread unrest in the country in support of two reformist candidates, Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, who believed that the polls had been rigged.

After a year of demonstrations and civil disobedience – called the Green Movement – Mousavi and Karroubi were put under arrest, accused of inciting chaos. The marginalisation of the reformists by the political establishment had begun.

Although it was widely acknowledged that he was running to help Rouhani, Jahangiri’s stellar performance in the presidential debates last year had a similar impact, reviving reformist hopes.

“If we don’t have a strong candidate in 2021 election, it is clear that we are going to lose the game to the conservatives and hardliners,” said Saeed Laylaz, the undersecretary of the Executives of Construction Party of which Jahangiri is also a member.

Then came his undoing.

Resignation tossed out

The first blow came last summer. While Rouhani was forming his new cabinet, he asked Jahangiri to suggest a list of his favoured candidates to lead ministries, a source close to Jahangiri told Middle East Eye.

But in early August, when the new cabinet was announced, none of the people he had proposed had been selected. “Apparently, Rouhani had ignored him,” the source said.

Neither Rouhani, nor the reformist camp leader Mohammad Khatami accepted his resignation

- Source close to Jahangiri

Feeling removed from the decision-making process, Jahangiri quit, something he has never officially confirmed, the source said.

“Jahangiri had really resigned, but neither Rouhani nor the reformist camp leader Mohammad Khatami accepted his resignation,” he said.

Analysts have speculated that Rouhani and Khatami wanted to keep Jahangiri in the administration to help pushback against conservative policies and politicians.

Then in October his brother, Mehdi, head of the Financial Tourism Department and the vice chairman of the Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries, Mines and Agriculture, was arrested on allegations of financial crimes.

He added: "I hope that there is no political abuse and that justice, the fight against corruption and the rule of law are implemented equally for everyone.”

Mehdi Jahangiri has since been let out on bail.

'A Jahangiri dollar'

Jahangiri stepped back into public spotlight when the rial started to lose value against the dollar earlier this year. Appearing on television on behalf of the government, he said a solution was coming: the dollar’s official and black market exchange rates would be unified.

“Any unofficial exchange rate on the market will be considered smuggling from tomorrow,” he said in April. The government had enough dollars to meet demand, he said, and no one needed to worry.

The next day, reformist media outlets expressed happiness at seeing Jahangiri return to the centre of the decision-making process of the country.

Within a few days, the policies he had announced to calm the market turned out to be a disaster as the value of the rial fell even faster. The 42,000 rial price per dollar that Jahangiri had promised was nowhere to be found in exchange shops.

While government ministries and those with official connections went on shopping sprees, the state was unable to meet public demand for the greenback. Many people, desperate for dollars, headed back to the black market. The prices of imported goods quickly rose and many consumers and businesses were left scrambling. Protests ensued.

And this is when the public face most associated with the policy became a punchline for Iranians in the throes of economic crisis. “Which kind of dollar do you need?” another joke goes. “A normal one? Or a Jahangiri dollar?”

“Society does not look at him in the same way it did last year,” said Matin Ghafarian, editor-in-chief of the reformist Roozarooz news site. “The currency crisis dealt a huge blow to him.”

It took a few months for the government to publicly acknowledge that the policy had gone badly wrong. This time, it was the new governor of the Central Bank of Iran that unveiled the latest policy to bring the currency crisis under control rather than Jahangiri.

The new policy would allow a floating pricing of the US dollar and would accept the existence of a free market. In other words, said analysts, the opposite of the policy introduced by the first vice-president and a message that it had failed.

But the final blow came from Iran Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei who publicly chastised “the individual” who had provided the hard currency that allowed the government’s policy to move forward.

“A huge portion of the blame lies with the individual who has provided the foreign currency or gold coins with imprudence… who paved the ground for … a drop in the value of the national currency,” he said in a 13 August speech.

Although Khamenei never used Jahangiri’s name, it was widely understood among Iranians that he was pointing at the politician from Kerman.

Towards 2021

Despite the swift set of events dragging down Jahangiri’s reputation, some reformist stalwarts say he could still rise again and bring their movement along with him.

There were definitely mistakes made with the economic policy, said Laylaz, the Executives of Construction Party undersecretary. But all is not lost.

Matin Ghafarian, editor-in-chief of RoozARooz, an online news startup, agrees. “Firstly, I do not agree that the reformists do not have any other options. Mohammad Javad Zarif can be a good option,” he said, referring to Iran's high-profile foreign miniter. “Secondly, Jahangiri has still the chance to improve his reputation."

But Mahdi Rahimi, political editor of the principalist Mehr News Agency, said Jahanagiri has “lost all his chances”.

Jahangiri has lost all his chances

- Mahdi Rahimi, Mehr News Agency editor

“Although reformists have tried to distance themselves from Rouhani’s government over the past months and even called on Jahangiri to resign from the government, the people believe that the reformists and Jahangiri are an accomplice in the failures of Rouhani’s government,” he said.

Observers note that Rouhani and his inner circle have always opted for moderate principalists like the current Parliament Speaker Ali Larijani, instead of reformists, and it is likely that Larijani will be one of the main moderate principalist contenders in 2021.

With three years to go, Jahangiri’s star may yet rise again.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].