HSBC shuts accounts of Syrians in UK after 'lobbying' for Assad's cousin

By the time anti-government protests began to sweep Syria in 2011, Rami Makhlouf, a cousin of President Bashar al-Assad, had already become a figurehead for the corruption and clan politics that were driving demonstrations on the streets.

Described as "Syria's poster boy for corruption" in a January 2008 US State Department cable, Makhlouf was estimated to be worth $5bn before the outbreak of the uprising, presiding over a vast business empire and controlling some 60 percent of the Syrian economy.

One of his many prizes included SyriaTel, Syria's largest mobile phone operator.

In February 2008, the US Treasury imposed sanctions on "powerful Syrian businessman and regime insider" Makhlouf, describing him as someone who "improperly benefits from and aids the public corruption of Syrian regime officials".

It claimed Makhlouf had "manipulated the Syrian judicial system and used Syrian intelligence officials to intimidate his business rivals".

In May 2011, the European Union also put Makhlouf under sanctions.

However, according to The Guardian's reporting on the 'Panama Papers' scandal, Panamanian firm Mossack Fonseca was still servicing several companies linked to Makhlouf during the first months of the 2011 uprising - despite warnings by one of its own compliance officers that sanctioned individuals posed "a serious red flag". It was not until September 2011 that Mossack Fonseca actually cut ties.

Those same links also implicated one of the UK's leading banks - one with a growing record of closing accounts held by Syrian nationals legally resident in the UK, while citing as a reason the same sanctions originally aimed at people like Makhlouf.

Thanks to lobbying by London-headquartered HSBC, Makhlouf was able to maintain Swiss bank accounts until May 2011 - despite existing US sanctions and growing interest around Makhlouf from financial investigators in the British Virgin Islands.

As The Guardian reported on Tuesday, leaked emails suggest that HSBC's compliance departments in Geneva and London argued against cutting ties with Makhlouf up until February 2011.

By 2014, campaigners claim, HSBC began arbitrarily closing dozens and dozens of bank accounts held by Syrian nationals living in the UK, doctors and students, refugees and activists - often with little or no explanation at all.

But why?

Yasmine al-Nahlawi, advocacy and policy coordinator at Manchester's Rethink and Rebuild Society, a community centre and advocacy organisation that works with Syrians in the UK, told MEE that the HSBC joint account she and her Syrian husband shared was suddenly "inhibited" in January 2014 during a routine visit to a branch in Manchester.

Before the meeting, the branch requested they bring either a driving licence or passport to the appointment. Nahlawi's husband's passport was in Paris for renewal, because the Syrian embassy in London halted consular services in 2012. So, he presented his driving licence instead.

"They said, 'We're going to have to inhibit your account until you can produce your passport'," Nahlawi said. Asked for an explanation, an HSBC employee referred them to the bank's terms and conditions, stating the bank had the right to block or close an account where there was suspicion of financial crime.

"They were making very big allegations and that needed to be supported by fact, not suspicion. We didn't have any money going in or out of the country using this account, let alone Syria. We didn't have any shady transactions."

Although the couple's account was unfrozen in March that year, Nahlawi realised her's was not an isolated incident.

"When we started telling others about what had happened to us, we realised there was a pattern of bank account closures happening to Syrians all across the country," she said.

Others have reported receiving letters from HSBC giving them two months' notice before a closure.

Majid Maghout, then a 26-year-old student, told The Independent in 2014 that he never received a letter, only discovering his account had been closed when he tried to withdraw cash.

"HSBC told me it had nothing to do with me as customer," he said. "The issue was that I was a Syrian citizen."

Although the story hasn't been reported since then, Rethink and Rebuild Society's campaigns coordinator Sara Ayub says the trend has not stopped.

"We're getting more cases documented and more people are coming forward," said Ayub, who has been compiling a body cases, some of them as recent as the end of last year.

"This is happening across the Syrian community. The last person to contact us was a pharmacist. We've had people who have refugee status, as well."

"The problem is a lot bigger than what we're documenting," Ayub added. "Almost everyone we've spoken to has said that they have friends or relatives who've experienced the same."

When asked for comment, a HSBC representative said that decisions to close accounts were "not taken lightly, and are never due to the race or religion of a customer."

"The bank is applying a programme of strategic assessments to all of its businesses. It is not always possible to be specific about why an account has been closed," HSBC said.

"However, in reviewing customer relationships we take into account a wide range of factors including the nature of their business activities, the jurisdictions in which they operate and the products and services they use."

This contrasts with evidence from people like Maghout or Nahlawi, as well as those documented by Rethink and Rebuild Society, where Syrian customers often say they have not sent money abroad or engaged in suspicious financial activities.

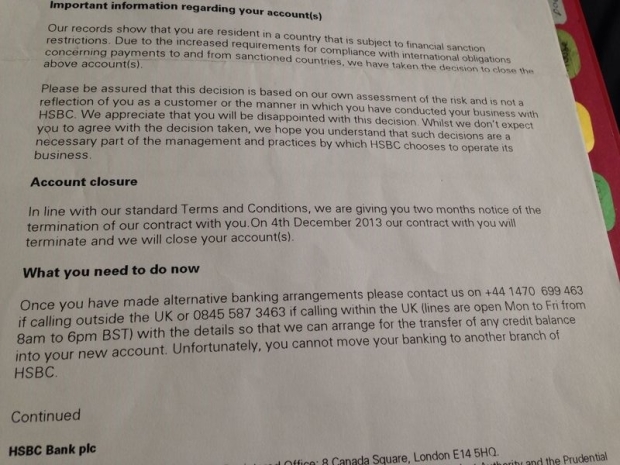

According to a letter sent by HSBC to a Syrian customer, which was shown to Middle East Eye, decisions are "based on our own assessment of the risk... not a reflection of you as a customer or the manner in which you have conducted your business with HSBC".

The letter mentions "increased requirements for compliance with international obligations concerning payments to and from sanctioned countries" because the customer is "resident in a country that is subject to financial sanction restrictions".

Tom Keatinge, director of the Centre for Financial Crime and Security Studies (CFCS) at the Royal United Services Institute, says that given the burden of work when reviewing accounts, banks "may use a sledgehammer, rather than a scalpel".

"If, by nationality, you [the account holder] are linked to a country that is deemed by the bank in question to be high risk, then you're immediately in a category of risk that is higher than your next-door neighbour... who is just a UK citizen," Keatinge said.

"Your national links may present a risk…even though you may be living here."

Some have accused HSBC of double standards, carefully aiding a Syrian regime lynchpin in 2011 before shutting down dozens of accounts held by ordinary Syrians just a few years later.

However, Keatinge said steps like this may actually be as a result of banks' previously dubious financial dealings, making them more careful when assessing risk and implementing more "de-risking" (or de-banking) measures.

"Because they've suffered in the way they have suffered... banks swung the pendulum the other way. So there's got to be a very good reason to keep someone on your books if there is any sort of hint or connection with a sanctioned nation or regime."

Under a 2012 deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) between HSBC on the one hand, and the US Department of Justice and UK Financial Conduct Authority on the other, a monitor was installed within HSBC in 2013 to ensure that the bank improved its sanctions compliance programme.

According to HSBC's latest annual report, the monitor "expressed significant concerns about the pace of that progress, instances of potential financial crime and systems and controls deficiencies".

It doubted on whether the bank would fulfil its requirements under the DPA.

Arguably, this opens up the possibility of more account closures in the future - cold comfort for those who've already been on the receiving end of de-risking by HSBC and other banks.

Nahlawi says that even if the bank is trying to "stick to the books", that shouldn't result in blanket policies affecting ordinary people.

"What we're arguing is: we're not asking you to violate your sanctions, we're asking you to assess things on a case-by-case basis," she said.

"Sanctions doesn't mean blanket discrimination against civilians."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].