Winter weather, not EU policy, behind recent drop in migration

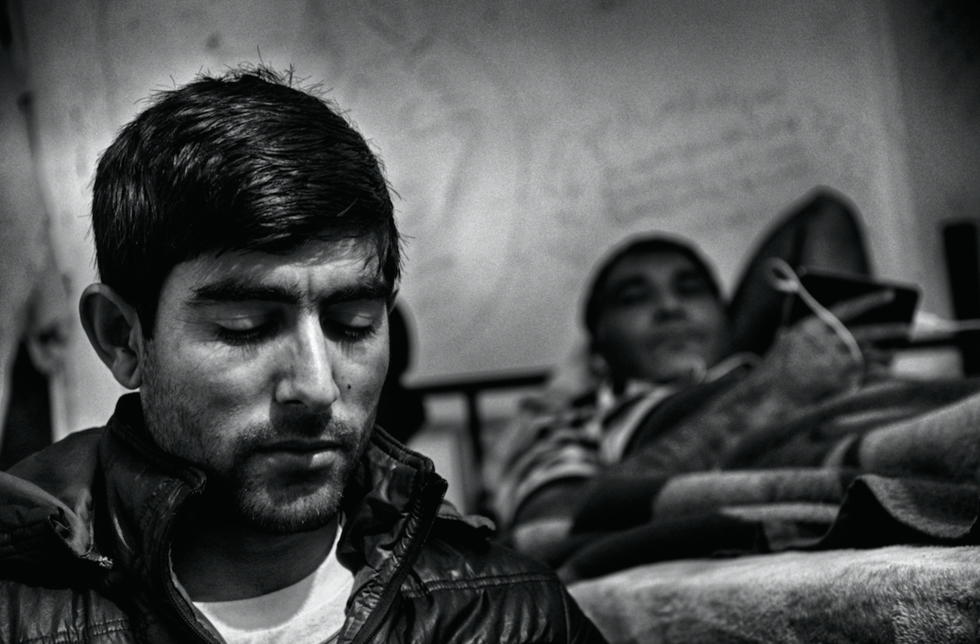

BELGRADE - The young Afghan man shivers in a thin coat as a chill wind whips around him and his friends who had recently arrived the Serbian capital in hopes of reaching Germany.

“It’s very, very cold and we don’t have coats and jackets or the right shoes,” he said, as the group contemplated what to do from here.

The man, in his early 20s who did not want to give his name, said that months of preparation in Afghanistan were overtaken by events as European nations began tightening their borders and refusing refugees.

His hand was forced, despite the onset of winter.

“I had been planning my journey for a long time but we could not wait any longer. We were worried the borders would shut and we would lose our chance, and maybe even our lives, if we waited. The situation [at home] is very dangerous and getting worse all the time.”

As the world marks International Migrant day on Friday, and looks back at a year that has seen almost a million migrants and refugees enter Europe, a 200 percent rise on 2014, Europe's focus is on trying to stem the flow of refugees in 2016 in the face of new waves of people fleeing war and desperation.

For the time being, harsh weather conditions and tougher border controls have slowed the influx of refugees into Greece and the Balkans. The number of new arrivals into Greece more than halved last month, with even fewer people braving the dangerous trip by boat from Greece to Turkey in December.

Camps which were once filled to the brim have in some cases been left empty. Volunteers in Serbia and Croatia, which form an integral part of the Western Balkan migrant trail, have gone from registering thousands of arrivals a day to a couple of hundred.

But with millions of people still desperate to escape war in the Middle East and other conflict zones, the feeling is that the halt can only ever be temporary and people will find alternative ways through. On Wedesday alone, some 4,300 people arrived in Greece despite bad weather, with the ILO saying the influx remained "robust and dangerous". Save the Children also told MEE that the proportion of people arriving with young children has remained the same with minors under 18 now making up 28 percent of new arrivals in Greece, up from 21 percent in September.

Those that continue to come now despite the increasing risks at sea and overland during winter say they are rushing through out of a fear that the borders will shut around them. Many regional borders have already been closed to those not from Syria, Iraq or Afghanistan, with hundreds of people stranded with nowhere to go, but even for those deemed to have the right nationality, the feeling is that time is running out.

Hasannin Tammim a 26-year-old who fled Baghdad earlier this year in hope of reaching Germany or Sweden, has also found himself stuck in Serbia, this time in an asylum camp where he says he now has to wait for months until his friend recovers from a car accident in a local hospital.

“My only concern is to get out before they shut the borders. It is getting harder all the time and this is all I think about every day,” said Tammim.

“I could not stay in Iraq. The Shia militias keep growing stronger and they are making all the young men in my neighbourhood join – saying that it is our duty to fight Daesh – if you say no, they beat you and sometimes they take you anyway,” he added, using the Arabic name for the Islamic State group.

While Germany opened its borders earlier this year, letting hundreds of thousands through in a matter of weeks, many states have since worked hard to stem the flow. Hungary has erected a border fence, with Macedonia following suit. The EU has also held emergency talks with Balkan states and with Turkey, which in late November pledged to ramp up border security in exchange for a $3bn pay-out slated to be paid out over the next two years.

In the latest developments, on Tuesday the EU unveiled plans for a new 1,500-strong border and coast guard agency that could intervene without the host country's consent, saying it had to restore security.

On Wednesday, Amnesty International accused Turkey of rounding up Syrian refugees by the hundreds and forcibly repatriating them despite there being no reprieve to the bloody civil war in which more than 250,000 people have been killed and millions more displaced. Turkey strongly denies the charges and points out that it has hosted more than a million Syrians for years, although reports about growing hostility to refugees in once widely receptive Turkey have been growing.

Disappearing refugees

But while the feeling of urgency may be fuelling some refugees and migrants to speed up their journeys, the situation is far more complicated.

Anne Davidson, a former British nurse who has been volunteering on the Turkish coast since May, says that she has seen a marked decline in new arrivals.

“Before the smugglers used to hide people up in the hills. They would give them dinghies and make them inflate them before setting them off,” she told MEE.

“The coastguard would only really intervene if the dinghies got into trouble. People were then usually detained there for 24 hours then detained by the gendarmerie for a further 24 hours and then as far as I am aware they would set them free.”

“But now it’s not clear what is happening. I am not seeing nearly as many people. They just seem to be disappearing - but I know from my contacts [on the Greek island of Kos and elsewhere I know] that people are still getting through in spite of everything.”

While restricting migration was a key part of the EU deal, a senior official from the Turkish prime minister's office told MEE on the condition of anonymity that the coast guard has been operating at full capacity since the early summer and that it will be virtually impossible to increase patrols even if Ankara wanted to.

“There is no change in that regard after the agreement with the EU. What has changed, however, is that our ground operations have intensified,” said the official who stressed that only smugglers were being arrested and sent to camps and other refugees were being released as usual and that many of those would likely try to cross again.

Oz Katerji, a Lesvos project coordinator for Help Refugees UK, who has helps to receive refugees once they arrive in Greece, also says that his teams have noticed a decline but that they do not plan to stop work any time soon.

“The Turks rounded up a few hundred people [but they] probably released them after a few days,” said Katerji.

“The boats are still arriving daily. The numbers have dropped a bit in Lesvos especially as boats aren't arriving on the north coast as often, [and instead the] boats have started arriving on the south because the Turks were making a better effort to control the coastline that [the refugees were previously leaving from]. But no matter what the Greeks and Turks do it seems like there is no way to stop the boats indefinitely.”

Save the Children likewise told MEE that they were planning for a tough 2016 and were "aiming to scale up our child protection work in 2016" with the aim of and being "wherever children and families need us to be".

Bulgarian wall

The border crackdown has been accompanied by an apparent uptick in smuggling through Bulgaria. While a few months ago, the overwhelming majority of new arrivals into the Balkans came on boats from Greece, a significant number in recent weeks has been saying that they have opted for the overland crossing from Turkey where they have had to pay high fees to and put themselves at the mercy of smugglers.

The Bulgarians were the first EU country to be impacted by the refugee influx from Turkey in the summer of 2013 when hundreds of largely Syrian refugees flooded through. By September 2014, however, the country erected a 30-km long wall on its border with Turkey which it then gradually expanded. The wall of razor wire is now almost five metres high, and 1.5 metres wide in places and stretches for more than 80 kilometres.

But while it means people cannot cross, it has failed to dissuade smugglers who have charged higher and higher prices to get people through, often abandoning them close to the border and leaving them to try and reach Serbia alone. Many arrive with bruises and stories of assault by Bulgarian police and smugglers. Muggings are commonplace and concerns have been raised about rape, with volunteers fearing the worst could be happening to female refugees who are too scared to speak up.

A Syrian Kurd who asked to be called by his initials SM and had recently entered Serbia from Bulgaria with his five other members of his extended family, said that they had each paid a small amount to local smugglers to be taken out of Syria into Turkey and then paid a further $3,500 to smugglers to be taken from Turkey to Bulgaria.

There they were left to fend for themselves for days, walking in the woods and sleeping out in the open in temperatures that hovered not much above zero.

“Life is very bad and everyone has left [Syria],” SM, who has trained as a doctor and was going to Germany in hopes of specialising further. “The Kurdish forces have pushed back Daesh [from our border town] for now, but there is always the threat of bombs and fresh fighting.

“The economy is very bad. The Turks have closed the border [with the Kurdish areas north of my hometown of Qamishli] and they are not letting anything through. That is why we had to pay smugglers to get us across. [It is also why] there is less and less food and what there is is getting increasingly more expensive.”

“We understand that the borders are getting harder to cross and the measures are tightening up but we are fleeing war. We will keep coming no matter what, we have no other option.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].