Architecture and war: What Syria needs to know before it rebuilds

In her first book, The Battle for Home: The Memoir of a Syrian Architect, Marwa al-Sabouni illuminates the way in which buildings inform the societies we live in, joining people together or participating in their collapse.

Through the history of her own nation, she explains how Syrian architecture, because it failed to meet the needs of its unique identity, has gradually divided its multi-denominational population.

The architect takes us through different periods in her country's history, from Umayyad palaces and buildings from the Ottoman era, to those of the French mandate and the ruins of Homs.

It's a journey that meanders through the conflict of the country that, far from drawing a gloomy picture of the situation, offers the hope of healthy reconstruction which could finally reconcile Syrians to their built environment.

Middle East Eye: What is the role of architecture in your opinion?

Marwa al-Sabouni: Whether it's private or public spaces, the architecture of places affects people's lives on many levels. It must be both beautiful and enjoyable, while also allowing each one to connect and live together.

MEE: In the book, you take the example of your hometown, Homs, to illustrate the role of architecture in the community.

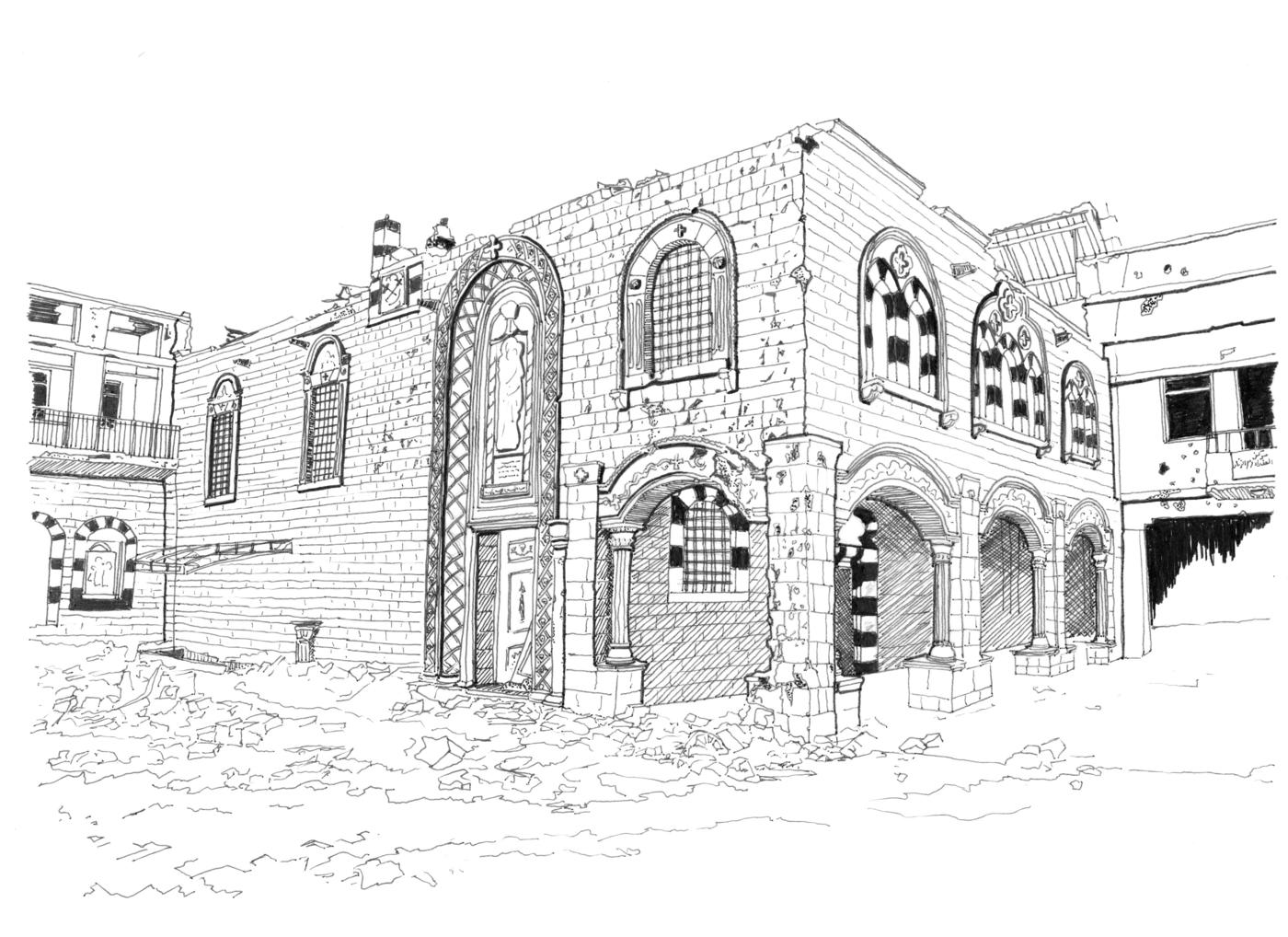

MS: I'm talking mostly about the old part of the city. Old Homs was a living museum of ancient architecture but its treasures were abandoned.

In particular, I think of two buildings of the city that became iconic for its inhabitants because they are of sentimental importance for Christians and Muslims: the Ottoman mosque Khalid ibn al-Walid and the Saint Mary church. In addition to their importance to Homs's inhabitants, these two buildings have also undergone significant degradation in recent conflicts.

The social fabric was built on the same principle as that of architecture: a mixture of customs, origins and religions. Often the bells of the Christian churches and the call to prayer of the Muslims resonated together in the street. Values that should have been protected, because today they are sorely lacking.

The Old City helped to give the inhabitants a sense of community. Everyone lived in a community thanks to the very configuration of the houses, which promoted cohesion: their proportions, height, alignment, shapes and the materials used had been thought of as an integral part of the city.

Today, the more modern part, located on the outskirts of the city, has composed itself as an agglomeration of neighbourhoods based on the demographic origin or religion of its population.

MEE: Has the Syrian government failed in the planning of an architecture that allows its inhabitants to live together peacefully?

MS: The government has failed at many levels by neglecting the basic functions of architecture: the aesthetic, social, economic and even political aspects that buildings should provide.

Rather than preserve the old part of the city and improve the new, city officials decided to "update" the town planning and architecture. A lot of old buildings have been destroyed, replaced by fantasies out of their imagination.

One day, for example, the municipality decreed that the shopping centre in the heart of the old town would be provided with open parking. Lifeless concrete masses have replaced palaces, baths and other buildings of historical and aesthetic importance.

Another massive construction, the Ibn al-Walid complex, has not been completed and now looks like a malignant wart. This project was designed and built by the military construction company, the prime contractor of public projects in Syria.

On the rare occasions when officials have opted for preservation and restoration, the results have been disastrous, such as the al-Zahrawi Palace, for example, which became the property of the Syrian government in 1976. The official restoration staff did not respect the harmony and coherence of this magnificent building and have repainted it with flashy colours.

MEE: How did architecture precipitate the Syrian conflict?

MS: The Syrian conflict is the subject of a series of events, of which architecture is a tiny part. If I speak mainly of Homs in my book, it’s because it follows a pattern you can find in other Syrian cities.

Old Homs, which is both the heart of the city and its historic district, was originally built inside the ancient walls that protected the city from invaders. It was in the 1940s that the city extended beyond the area circumscribed by these walls. At this time it was surrounded by lush orchards that grew near the Assi river.

'Even before the war, the erosion of the old quarters of Homs helped to disconnect the inhabitants from the city and themselves'

- Marwa al-Sabouni, architect

In the 1950s, the promulgation of an expropriation law allowed the government to confiscate private property for public use, paving the way for massive construction outside the city limits.

In this new sector, which became the new downtown, urban planning has extended the Old City in a heterogeneous way, mixing elements of colonial architecture with constructions without real identity or meaning.

The third sector includes more residential neighbourhoods with middle and upper-class homes, whose architectural elements range from the "experimental modern" to the nil of anti-architecture.

Even before the war, the erosion of the old quarters of Homs - and, above all, their replacement by new ones based on religion or the demographic origins of the population - helped to disconnect the inhabitants from the city and themselves. At the beginning of the conflict, people found themselves cloistered in certain areas of the city because of the bad decisions of the authorities in terms of urban planning.

MEE: You also refer to an amalgamation between Arab and Islamic architecture. What is Arab architecture?

MS: Arab architecture does not exist. When the Ottomans were defeated by the Arabs, talk began about Arabism in order to create unity and so the concept of Arab architecture appeared. The idea of Arab architecture is a political construction.

There is, on the other hand, Islamic architecture, which you can see in the monuments and structures of many Arab countries. What appeared afterwards was only imported European architecture.

MEE: What is the main problem with architecture in the Middle East?

MS: The main problem is that it is the object of a colonial legacy that the old powers left us and not a national creation. In Syria, the new urban schemes were planned by the French and implemented after independence.

Architecture must allow people to feel at home by finding unique forms of expression and production that are not just about importing architectural plans from abroad.

We have had an inferiority complex for decades, a social illness we should get rid of by trying to have a better understanding of our history in order to find our own way.

MEE: Are you nostalgic for the traditional architecture of the Ottoman era?

MS: It's not a matter of nostalgia but rather of rationale. My message is this one: let's try to observe and analyse what has worked for us in the past and start building on the basis of those lessons.

MEE: Do you remain optimistic about rebuilding your country?

MS: As a citizen of this country, I have to keep hope, otherwise there is no reason to live. If the Syrian conflict seems to painfully be coming to its end, then the reconstruction of new infrastructures capable of hosting a bruised, dispersed and, more than ever, divided population seems necessary.

It is a mission that can only be realised after deep reflection on national identity and past mistakes, in order to find a common culture that can be expressed in space and the environment.

This article is also available to read as part of the French edition of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].