How Bouteflika plans to bounce back

After more than a week of uncertainty, Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika seems to have regained control, in an attempt to resolve a seriously compromised situation.

Anticipating a strong mobilisation of the Algerian street on 15 March, the Algerian president wants his opponents, but especially his allies and partners, to know that he is in charge and intends to remain in office.

Bouteflika, who was hospitalised in Switzerland from 24 February to 10 March, watched things fall apart. The street was roaring, and the political system no longer showed the same discipline. Strongly discredited, his supporters were forced to remain silent. Some even had to pay tribute to the demonstrators who insulted them daily.

Illegal sleight of hand

This week, Bouteflika notified Algerians that he was still the game-master. In a spectacular turnaround, he decided to illegally postpone the presidential election scheduled for 18 April, and stated against all evidence that he had not intended to run for a fifth term, even though a candidacy in his name was submitted to the Constitutional Council by his campaign director.

Bouteflika also promised a reform package, including a national conference and a constitutional revision, topped by a presidential election in which he would not be a candidate. In the process, former interior minister Noureddine Bedoui was brought in to replace former prime minister Ahmed Ouyahia. Ramtane Lamamra was named deputy prime minster, a newly created position.

For Bouteflika, however, the main threat is not in the streets, but within the government. What matters most is to maintain the support of the army and security services

Lamamra, a former foreign minister, is expected to promote the president's decisions to foreign countries. He is backed by an Algerian diplomacy veteran, Lakhdar Brahimi, who holds no official position. The two men immediately got into action by speaking on Wednesday, one hour apart, on the radio and public television. A press conference was scheduled for Thursday.

This operation is intended to ensure the success of the Algerian president's remarkable sleight of hand. "We did not want a presidential election that would inevitably lead to Bouteflika's fifth term, and now we have Bouteflika but with no election," a protester in Algiers told MEE.

Louisa Ait-Hamadouche, a political science professor at the University of Algiers, said that Bouteflika "renounces the fifth term but is extending the fourth term, which poses a major legal problem. As of 28 April, he will no longer be able to legally exercise his responsibilities."

Mustapha Bouchachi, a lawyer, former politician and protest leader, spoke of a "great manipulation" carried out in "violation of the Constitution," noting: "Entrusting the transition management to the government is not serious." He vowed to continue protesting.

Preserving unity

For Bouteflika, however, the main threat is not in the streets but within the government. What matters most is to maintain the support of the army and security services. He needs to preserve unity in the circles around him, even if that means dismissing Ouyahia, who has crystallised some of the popular anger, and asking others to remain discreet.

For the army, the situation remains under control. This is especially comforting for Bouteflika after the army's chief of staff, Ahmed Gaid Salah, had previously raised concerns. After calling the protesters "misguided," the army boss made a significant change in his rhetoric, stating on Sunday that "the people and the army have a common vision for the future".

That said, Bouteflika himself said on 11 March that he "understands" the demonstrators and "pays tribute to the peaceful character" of the protests, suggesting that Gaid Salah's tone change was rhetoric.

At the same time, a change has been noticeable among the men who traditionally act on behalf of the Bouteflika circle. This has been seen in the administration, public media and the nebula of organisations that gravitate around the presidency.

Calming the protesters

This could have meant that new teams were arriving, but in fact it was the replacement of men considered to be less effective - or who had become very unpopular - by new staff with the same background or coming from the same matrix. The most emblematic of this was the replacement of Ouyahia with Bedoui.

For Bouteflika, it is therefore time to carry out political rearrangements to contain the streets and preserve his own agenda through to the summer of 2020. It is difficult to imagine a national conference, a constitutional referendum and a presidential election occurring before that date. He had already proposed this while still running for office on 3 March.

As for the streets, Bouteflika pays little attention. For the time being, it is a matter of calming protesters by borrowing their vocabulary, or even flattering them. Then will come the manoeuvres and intrigue. This is not specific to Bouteflika, but to Algerian rulers in general, although the current president has raised the strategy to new heights.

A disillusioned former activist noted that "under Bouteflika, after each protest campaign, prominent protesters are recruited into the teams of ministry advisers".

Emblematic opposition leaders could not resist this seduction, including former RCD party president Said Sadi, who had supported Bouteflika's first term, or Khalida Toumi, who was his culture minister for nearly a decade.

The case of Bendjedid

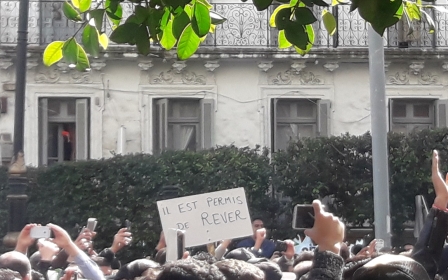

But this time, the game is more challenging. A significant proportion of the population held massive protests, despite a ban on such activity, with the main demand being the end of Bouteflika's presidency. The attack is frontal. The mobilisation has been impressive and promises to grow steadily, as has happened for three weekends in a row.

This shows the impasse in which this very diminished man, haunted by power, finds himself at the end of his life

This time, intrigue cannot suffice to derail the movement. Bouteflika must certainly recall the path taken by Chadli Bendjedid, president from 1979 to 1992, who succeeded in rebounding after the October 1988 riots by engaging in a process of democratisation and bold reforms.

But Bendjedid was convinced of the importance of these reforms, which is not the case for Bouteflika, who considers them as a necessary evil to maintain his power. Apart from his supporters, it is difficult to find people who believe in his will to reform. This shows the impasse in which this very diminished man, haunted by power, finds himself at the end of his life.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

The article originally appeared in the MEE French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].