Hoping for peace, preparing for war: Libya on brink of Tripoli showdown

After taking large areas of southern Libya and two key oil facilities earlier this year, Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, operating under Libya's eastern-based government, has pulled his Libyan National Army (LNA) forces back from the south towards western Libya, in a move widely seen as paving the way for an assault on Tripoli.

We are ready, willing and able to take over Sirte, and we are just awaiting orders to advance

- LNA fighter

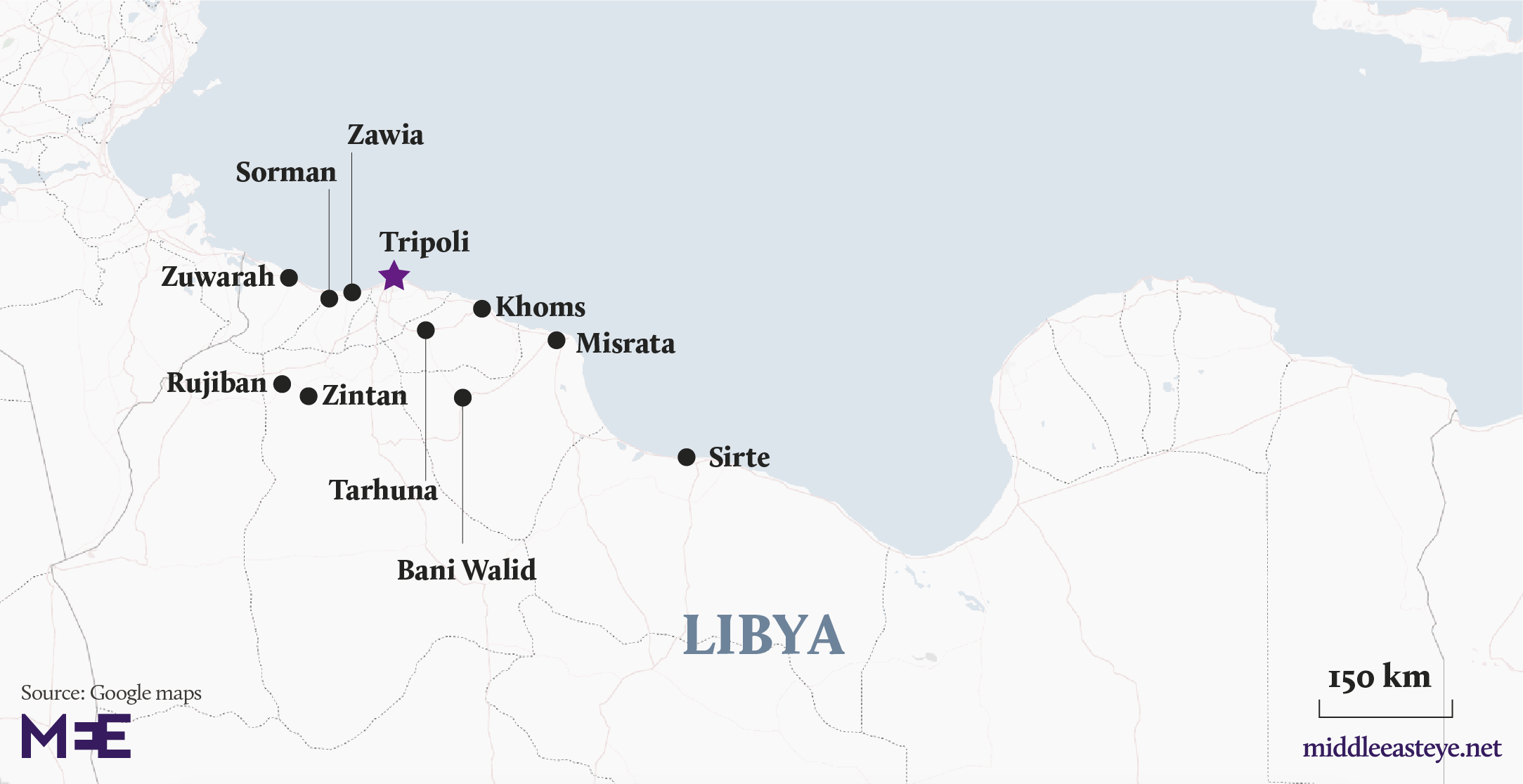

A military build-up of LNA forces south of Sirte in recent weeks has prompted previously quiet factions in other western Libyan towns to openly pledge support to Haftar, threatening Tripoli from several directions.

Even while the international community is still trying to broker a peaceful solution, Tripoli militias are preparing to defend the capital.

On Wednesday, a convoy of around 100 military vehicles was seen heading out of the capital on the road leading towards the town of Tarhuna, according to Ahmed, a local resident, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

"There were about 100 of them. They were militia vehicles, not army vehicles, but I don't know which militias," he said.

Most Tripoli militias currently support the UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA), which sits in the capital. The GNA also has the support of the Misrata-based Bunyan al-Marsous (BAM) forces, which continue to secure Sirte after leading the battle to defeat the Islamic State (IS) there in 2016 and view Haftar as a long-standing foe.

Former BAM spokesman Major General Mohamed Al-Ghossri has already stated that any LNA incursion on Sirte would be treated as a declaration of war.

"Bunyan al-Marsous and all of Misrata stand with the GNA," he told MEE. "We are always ready to fight against any possible aggression in Sirte and have not lowered the threat alert, or our duty of providing security and surveillance there, since 2016."

Ghossri said no reinforcement troops had yet been sent to Sirte, but he confirmed that Misrata had enough forces to defend its present territories, including a 250 km stretch of coastal highway.

Tripoli threatened from east and west

Following his southern advances this year, Haftar has pulled most of his forces back towards Sirte, in a move widely viewed as paving the way for an eventual assault on Tripoli.

What we expect here is that the LNA will keep us occupied with a little fighting around Sirte, so we are unable to help defend Tripoli

- Hassan, BAM fighter

An LNA fighter, speaking on condition of anonymity from a military position between Sebha and Sirte, told MEE earlier this week: "We are ready, willing and able to take over Sirte, and we are just awaiting orders to advance."

However, BAM fighter Hassan, manning a strategic checkpoint at the village of AbuGrain, 100 km from Misrata and 150 km from Sirte, told MEE that the threat of clashes in Sirte was a red herring. A greater threat, he claimed, was posed by LNA troop movements towards the inland rural towns of Tarhuna and Bani Walid where, he said, Haftar had been gathering ideological support.

"Yes, Haftar probably will take control of Tripoli, not with these troops moving from the east, but rather with troops from western Libya," he said.

"I'm unhappy with the GNA's understanding of the current situation. What we expect here is that the LNA will keep us occupied with a little fighting around Sirte, so we are unable to help defend Tripoli, which will be taken by LNA military operations coming from western Libya."

Haftar has a growing support base across western Libya from towns left disenchanted by post-2011 chaos and disillusioned by the GNA which, in three years, has failed to have much meaningful impact beyond the capital.

Growing support for LNA in western Libya

Although a key Tarhuna militia appears to be siding with the LNA to reach the town, Haftar's forces would need to pass through the town of Bani Walid, which has been a no-go area for any government forces since a brief but bloody civil conflict with Misrata in 2012.

The town now functions as a largely independent entity and bastion of pro-Gaddafi sentiment which freely flies the plain green flag that represented Libya under 42 years. Its present allegiance remains unclear but Bani Walid has long disassociated itself from any Tripoli-based powers and is likely to align with any forces against Misrata.

While Tripoli's militia forces head to Tarhuna, further west, Haftar's support base is also consolidating. In the past fortnight, the military council of the mountain town of Zintan has pledged support to the LNA, although several senior Zintanis and their associated militias currently remain aligned with the GNA.

Zintan - famed for capturing Saif al-Islam Gaddafi in 2011, keeping him imprisoned for six years while ignoring attempts by the International Criminal Court (ICC) to have him tried for war crimes, before eventually releasing him in late 2017 - was formerly aligned with the LNA until the relationship deteriorated early last year.

The LNA also has full control over the al-Wattiyah military airbase west of Tripoli, thanks to Zintan gaining the upper hand in a conflict with Misrata over the facility in 2015.

Another powerful former revolutionary mountain town of Rujban and the small town of Sorman, lying 60km west of Tripoli, have also pledged support to the LNA.

Although to the outside observer allegiances of such technically small towns may seem unimportant, a strong network of local and tribal support is key to Haftar's potential success in gaining more territory in western Libya and crucial to any progress towards the capital.

The eastern government and its LNA forces also have firm pockets of support inside the capital, including in districts mercilessly crushed by a former Tripoli-based government in 2015 for voicing support of Haftar.

There even appears to be some LNA support to the east of Tripoli, with a civilian group in the strategic coastal town of al-Khoms, lying between Misrata and Tripoli, also declaring their support for LNA forces this week. If this move is supported militarily, local forces from al-Khoms, which control a key checkpoint on the main coastal highway, could strike a strategic divide between Misrata and Tripoli.

Much of Libya has been left disenchanted by failing democracy. To some, a viable future under a strong, unified and stable leadership, holds appeal

Most other former revolutionary towns that supported the 2011 uprising against Muammar Gaddafi, including the Amazigh coastal enclave of Zuwara, remain largely with the GNA, at present. However, with post-2011 country-wide discontent, many western Libyan towns increasingly stand divided, according to Tripoli resident Ahmed.

It is not surprising that Haftar has been able to secure support. Neglected and sporadically isolated by ongoing civil wars, residents in western towns outside Tripoli have grown tired of waiting for the GNA to make meaningful improvements on the ground.

Haftar, who has presented himself as a "strongman" capable of leading military victories, represents, to some, a potential solution to the troubled country that post-2011 Libya has become.

Although there are fears of another Gaddafi-style autocratic leader, much of Libya has been left disenchanted by failing democracy and, to some, a viable future under a strong, unified and stable leadership holds appeal.

Is a Tripoli war inevitable?

Although Haftar has allegedly received backing from France, Russia, the UAE and neighbouring Egypt, much of the international community, including the UN and the US, stand against him.

Despite, or perhaps because of, Haftar's increasingly popular appeal, such external powers are continuing to push for negotiations, settlements and future general elections, which have been impossible to hold for the past five years. Such efforts to broker a peaceful unity have consistently failed.

Tripoli's last major conflict was in 2014, sparked by rival political parties dissatisfied with the outcome of Libya's last national elections. Fighting destroyed key civilian infrastructure - including the international airport - and left the country with two rival governments, parliaments and military forces.

Tensions over the capital have existed for five years, but military forces loyal to rival governments were kept busy with local conflicts and battling militant groups, including IS and al-Qaeda affiliates, putting Tripoli on a back-burner.

The GNA, boosted more by international recognition than local support, is ruling an increasingly compact area of western Libya, after recent LNA advances left the eastern government technically controlling the lion's share of Libya's geographical landmass, although not its key western cities.

Despite recent troop movements and political machinations, the reality has long been that Libya's vast size and small - about six million - population, has proved to be an insurmountable obstacle for any of the country's successive faltering governments, or militia-heavy armed forces, to assume full control.

Both governments still have limited forces comprised largely of semi-autonomous militias with fluid and unreliable allegiances. But Libyan civilians in western and eastern Libya told MEE they believed that Haftar now had enough military power and on-the-ground support to retake the capital.

Divided loyalties

The 2011 uprising which overthrew Gaddafi has left an eight-year legacy of mistrust. Former enemies have had to grudgingly ally with one another to face up to new foes, whether neighbouring towns or IS.

Present allegiances are often as fluid as past ones, most recently seen when the southern Tuareg tribe, formerly apparently loyal to the GNA, defected to the eastern government within days, during Hafter's southern advances.

Sirte, largely considered pro-Gaddafi, was liberated from barbaric IS rule by forces from Misrata, a sworn enemy since 2011. Although Misrata still has military control over the town, a senior Sirte official, who only gave his name as Mohamed, told MEE that, in reality, most residents supported the eastern government and the LNA, not least because the majority of the town's population is from the same Ferjani tribe as Haftar.

After failing to come to the aid of its southern supporters during Haftar's advances this year, the GNA appears to be trying to cobble together a more effective fighting force, with GNA president Fayez al-Serraj recently appointing former Gaddafi-era commander Salam Juha to the post of deputy commander of its official armed forces, such as they are.

Misrata-born Juha defected from Gaddafi’s military in 2011 to lead Misrata's revolutionary fighters, but later fell from favour for refusing to support Misrata's 2012 offensive against Bani Walid. He returned to Libya around a year ago after living for several years living in the UAE, a state at present backing Haftar.

Mistrusted by his home city, which provides the BAM forces upon which the GNA will rely to defend their easternmost borders against any LNA advances, Juha's appointment is controversial. Locally, Juha is also widely suspected of actually being politically aligned with Haftar, rather than with the GNA whose forces he is supposed to lead.

Although Haftar has not made any statement regarding his plans to move militarily on Tripoli, following another round of peace talks last week, he has appointed one of his top military personnel, Brigadier Abdulsalam Alhassi, to the role of Tripoli Operations Room Commander, an indication that he is not planning to back down.

As Libya again stands on uncertain footing, residents report that, across the capital, multiple checkpoints have been erected, mostly manned by local militias, believed to be an attempt to secure the capital from an increasingly real threat of a new civil war in western Libya.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].