The Turkish mother who brought the lives of village women to the world

Arslankoy, high up in the Taurus Mountains and 60km away from the south-coast city of Mersin, is much like every other conservative Turkish village.

Coffee houses burst with men and head-scarfed women bustle down the street. Those with an education have left for bigger cities; those that remain simply work the land.

Yet Arslankoy stands out for one reason: it is home to incredibly strong women. Seventy-two years ago the village’s women rocked the country as they fought against the army after attempts at election fraud by the then ruling party.

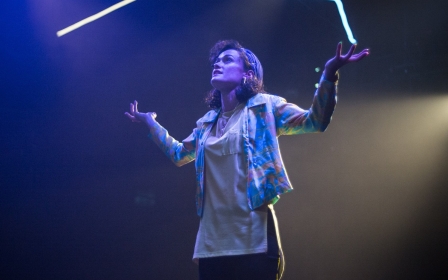

Today, it’s 62-year-old Ummiye Kocak making waves as she and her all-female theatre group draw attention to social issues ranging from domestic abuse to climate change.

Established in 2001, this theatre group has grown from seven women to a 60-strong troupe. For every new play Kocak writes, she creates a small cast, hands them a copy of her script and expects them to have learnt it in 10-15 days. Only once lines are memorised does she begin to direct their acting.

The group has toured Turkey, performed in Europe and, in 2012, made a short film – The Wool Doll (Yun Bebek) - that illustrated physical and verbal abuse against women, by women. It was so successful it won Kocak the "Best Eurasian Female Artist" award at the New York Eurasian Film Festival.

Every play, every tour and any sponsorship from the council or from charities is organised by Kocak herself; she has no secretary, just her son and daughter to help. Quite a feat for a woman who has had minimal education.

Self-taught

Sitting on a low stool in a small warehouse peeling walnuts, Kocak is smiling as she speaks of her unusual start to school life. “The mosque announced one day every family had to send one daughter to school. I was too old so they sent my younger sister. Three days later my sister refused to go again, crying that she didn’t like it, so I offered to go instead. My father gave me her uniform that instant.”

She says her sister doesn’t regret giving up her place. “She tells people that there’d be no Ummiye Kocak without her,” Kocak laughs, “but I tell her that even if I hadn’t gone to school, I’d have educated myself. I’d still be who I am today. If there’s talent inside you, it always finds a way out. You can’t stop it.”

Just like any other village woman, Kocak works in the fields and wears layers of brightly coloured knitted cardigans with a shawl wrapped round her waist, headscarf tied under her chin and baggy patterned shalwar. What sets her apart is her ability to constantly question.

The 62-year old began writing stories at the age of 13, inspired by a book she’d been sent to fetch for her teacher and had begged to read because the picture on the front reminded her of her grandmother. The book was Maxim Gorky’s Mother. She related to the Russian's poverty-stricken characters and their lives and thought that if he could write about such situations, so could she.

Her theatrical journey began late, though. “I saw my first play at my son’s high school when I was 45. As I watched, I kept wondering whether the actors were using their own names. I asked one of them afterwards what his name was. He said ‘Ali’. I was confused, a second ago it was Veli. He explained that Veli was the character’s name. I stayed up all night thinking about this.

“I realised I could take real situations happening in Arslankoy and reflect them onto the stage. By changing names it would be anonymous but relatable and I might just be able to make the voices of our women heard.”

Women's voices

Kocak’s first plays were therefore created using the complaints and secrets of her neighbours. Yet why the women’s voices in particular? “I was upset by the fact that women were working so hard – harvesting, cooking, looking after their children – while the men did nothing but spend their wife’s money on beer. These women needed to be heard.”

To a Western mind, this stance suggests that Kocak is a feminist. When asked, however, she firmly denies it. “I first heard that word ‘feminist’ when I asked the village school’s head teacher if we could rehearse plays there in the evening. I told him it would just be women, so there’d be no gossip. He asked if I was a feminist.” She didn’t know the meaning of the word.

She had decided to create an all-women group purely so that husbands would allow wives to join. “Of course, now I know the meaning and I’m not a feminist. I don’t like anything that’s extreme. I always like to find a middle ground.”

Success, as Kocak shows, has not come easily. Opposition and abuse from her village was rife when she simply suggested the idea of a group. But she would not be deterred.

She not only wanted the women’s voices to be heard, she also wanted their problems to be resolved. To her, theatre was - and still is - a method of educating those who haven’t had the chance to study at school.

The idea for her first film Yun Bebek grew from this perception. “In 2007, I heard an old neighbour reminisce about the abuse she had received as a child at her grandmother’s hands. This old lady just shook as she spoke.”

Kocak realised that a violent childhood has major repercussions and decided there and then to write about violence against women by women, in the hope of educating viewers. Yet, she knew directing a film would be different.

She took up small roles in soap operas, watching the trained actors, cameramen and directors at work between takes. Five years later, in 2012, she finally felt ready to produce her film.

Meeting Ronaldo

After the short film she appeared in a documentary broadcast on Turkey’s state TV network TRT. Then, in 2017, she got the chance to direct and appear in an advert for Turk Telekom with footballer Cristiano Ronaldo. Kocak – and consequently her theatre group – became a household name overnight.

“I had appeared in a documentary on TRT in 2016 when Turk Telekom contacted me. The advert was about achieving dreams and they wanted Ronaldo and me because we’d both done that.

“When I met him we bonded instantly. Despite being half his height and unable to understand his language, I hugged him and called him kuzum, my little lamb. He hugged me back and shouted ‘mummy!’ We had a connection. He had worked hard in the face of adversity to accomplish something. So had I.”

Since the advert was filmed, Ronaldo has been accused of sexual assault, which he denies.

'Love has no religion'

Kocak’s beliefs, like her personality, are strong. Her way of addressing her social media followers as "my babies" shows she is an advocator of love for everyone: “Just as tears have no colour, love has no race, language or religion. I’ve always believed this.”

Now she’s starting to express her beliefs on climate change. “It’s a very serious issue for the whole world and a solution needs to be found. It’s going to affect us in the Taurus Mountains, but I feel that Turkey doesn’t care. I’ve been abroad, I’ve seen how they recycle and take care of their forests. We need to do the same. That’s why I’ve written this new play.”

'Use terms like ‘global warming’ and people here don’t understand what it means'

- Ummiye Kocak

That new play, entitled Ahh, Someone Has Pierced The Sky (Ana, Gokyuzu Delinmis), focuses on using language familiar to the ordinary villager to explain climate change. It pleads for a change in behaviour and has the cast of eight physically join hands at the end in a call for us all to come together.

The group will be taking the play on tour across Turkey, starting in the north-western town of Balikesir.

“Use terms like ‘global warming’ and people here don’t understand what it means,” she explains. “We need to show them through situations they know.” Therefore, this play contains characters that could be found in any part of Turkey: gossiping neighbours, a woman everyone trusts, and a grandmother with Alzheimer’s.

Three women from the cast are sitting peeling walnuts with Kocak as she speaks. They come to life as the conversation turns to the play. They explain how they rehearse their lines in the fields as they work, and laugh as they tell of how they used to use coal or boot polish to draw moustaches for the male characters, before graduating to black lipstick.

Strong bond

They, like Kocak, are middle-aged, headscarf-wearing women in brightly coloured shalwar and cardigans. They too have lived their whole lives in this small village, growing vegetables, looking after children and cleaning their houses.

“I got bored of dealing with ordinary life. Acting was something different and I’m so happy I joined. I really enjoy doing it,” Memnune Kizir explains. “We’re all so proud of Ummiye.”

Do they think she is a good director? Of course they do.

“Don’t just say that because I’m here,” Kocak quips, her beady eyes twinkling. The women laugh together and one, Fatma Ay, pipes up: “Well, she’s not always a good director because she gets cross. Particularly if you don’t learn your lines.”

Do they ever have any disagreements over the plays? “We don’t argue with Ummiye, she’s been doing this for nearly 20 years now, she knows best,” Kizir adds.

“Whatever she has written on the page, that’s what we say,” another, Emine Yildiz, declares. Kocak’s eyes once again flash. “Girls, tell the truth, you want to change a line and I say no!” Peals of laughter ring through the warehouse.

'Because of her our self-confidence has grown hugely. I used to be so embarrassed but now I’m not at all'

- Memnune Kizir, actor

It’s evident that Kocak and her theatrical ladies have a strong bond. They respect her and she them. “Thanks to Ummiye, we’ve been educated through theatre. We’ve learnt so much,” Ay says gratefully.

“We’re finally doing something worthwhile,” Kizir adds. Yildiz looks at Ummiye: “Because of her our self-confidence has grown hugely. I used to be so embarrassed but now I’m not at all.” Kocak comes back at her with a joke: “Your confidence has grown a little too much - put the brakes on!”

In 2001, this lady only had the support of her family. It took knocking on 40 doors to get just seven willing women. Today, through hard work and determination, Kocak has won the support of her entire country. Now it’s her door being knocked on by women across the world for interviews and parts in plays.

She is resilient, intelligent and powerful. “I’m stubborn. I don’t give up,” she says. “If there’s something I want to do, I’ll do it.”

‘Ahh, Someone Has Pierced The Sky’ is touring Turkey until 25th October

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].