‘I sort of broke English’: Meet the Lebanese poet crossing boundaries

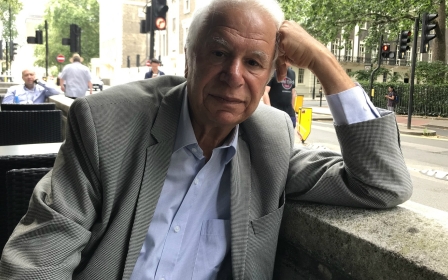

Zeina Hashem Beck sits in her living room in Dubai, wrapping vine leaves, wara’ ‘enab, over a stuffing of minced meat and rice, which she will later layer in a large pot, packing them tightly (“the Tripolitans roll them really small, really tight”.)

All the while, she’s keeping one eye on the rolling news coverage of demonstrations in her native country.

Less than two weeks since the launch of a protest movement calling for an overhaul of the Lebanese government, Hashem Beck is glued to events, which she tweets about, along with updates on her dinner preparations.

“In our house, we almost only have wara’ ‘enab at Eid: Eid al Fitr and Eid al Adha,” she says. “Maybe it felt like a Eid to me, like a sort of celebration...

“And we’re sitting anyway. Let’s just roll some wara’ ‘enab!”

'I want to create things!'

Hashem Beck is gifted with an irresistible charm, both on and off the page. Whether she’s tweeting about the protests or her cooking, she urges people to engage. Her poems are similarly inviting records of intense experience that readers are very welcome to witness.

“[Poetry] is the only way I know how to channel my creative energy, my emotions, my questions,” she says. “It’s how I process the world. When I was a little girl, I used to tell my mother: ‘I want to create things! I want to create things!’ It was almost a daily demand. Poetry [reading and writing it] is how I’ve learnt to do that.”

She’s since notched up four books, including two full-length collections, each bearing its own accolades. Her first full-length collection, To Live In Autumn (2013) won the Backwater Prize, while her latest, Louder Than Hearts (2017) won the Mary Sarton New Hampshire Poetry Prize.

'Poetry is the only way I know how to channel my creative energy, my emotions, my questions'

- Zeina Hashem Beck

Her poems have been sought out by editors of literary journals both in the Arab world and the West, where she is regularly invited to perform. And she seems at home in front of an audience.

For her, each performance is still a chance to create. When she found out that a choir from Tripoli were also due to perform at the 2016 Emirates Airline Festival of Literature in Dubai, Hashem Beck asked if they would collaborate on a special reading of her poem, 3arabi Song, which riffs off refrains common to classical Arabic songs. After a quick rehearsal in the hotel lobby in front of some bemused guests, her poem came to life on the stage, punctuated with stirring renditions of the Arabic music she tries so hard to relay through words.

Singers like Um Kulthoum, Abdelhalim Hafiz, Samira Tawfiq and the Iraqi poet Badr Shakir al-Sayyab are overtly referenced in her latest collection, Louder Than Hearts, but their influences also speak loudly through the rhythms of her own writing.

A natural storyteller, she honours the tradition she believes she inherited from her mother and her aunts. “I can never summarise anything.”

But her poems are tightly structured, the imagery vivid, at times both claustrophobic and expansive, like in her poem, Thirty-Two And In A Different Country, about a recurring dream in which she is a child watching soldiers infiltrate her home:

In the afternoon, the soldiers swarm

the building walls, like spiders.

[…]

You look at the small window, think, Jump.

You tell yourself you are thirty-two,

you are thirty-two and in a different country.

A response to family tragedy

Many of Hashem Beck’s poems are like capsules of memory she seems trapped within. She grew up in 1980s Lebanon, during the civil war, and themes of conflict, loss and trauma are prevalent in her work, but presented through accessible scenes, often domestic, from her own childhood through to her life now as a parent.

Many of Hashem Beck’s works are odes, to her family, to Lebanon and to her hometown, the northern city of Tripoli:

My town likes to boast she is the mother

of the North, which in Lebanese also means “left,”

which, she likes to remind me, is where the heart is.

Back home, she writes, when something went wrong, You Fixed It:

if there was a hole

in your sock you fixed it, learnt to fold it

under your big toe. And if your window shattered

you fixed it, taped cardboard to the frame,

But not everything can be fixed; published in 2016, Louder than Hearts inevitably refers to the various conflicts plaguing the region.

“As I was writing Louder Than Hearts, the Syrian war was happening,” she says. “And there were these images of refugees all over, you know, and of course, Palestine - it's always been happening.”

But the book itself was initially written in response to the summer of 2013, when her cousin was killed in a street shooting in Tripoli. A few days later, the city was rocked by twin mosque bombings. More than 40 people were killed and hundreds wounded.

Her poem, Listen, documents the moments that followed news of the bombings, which she heard about while at her mother-in-law’s house in the district of Koura, roughly 20 kilometres south of Tripoli:

You run to the balcony,

try to forget your brother might be

praying, you call, the goddamn line

is down, the whole town is down,

Arabic makes itself heard

It’s not all dark: Hashem Beck insists that humour must co-exist on the page as it does in real life. “Even during times of trauma or war…when you grew up in a country like Lebanon, humour is there, love is there, tenderness is there. Even in the civil war, people still eat, they still drink, they still dance, they make love.”

Untranslatable humour is one of her favourites: “With native English speakers, my friends, you'd say an expression in Arabic and then you try to translate it and you end up laughing because it sounds really weird in English, but makes total sense in Arabic.”

Arabic has a habit of infiltrating Hashem Beck’s poems. Some words, like “bayti”, meaning "my home", appear transliterated to a Latin script.

Letters that don't exist in the English alphabet she substitutes for numbers (like the 3 in 3arabi Song, which represents the letter ع), the way Arabic speakers might message each other - an informal style less commonly used in formal literature. At other times the language is presented in its original form, accessible to non-Arabic speakers only aesthetically: “رحلنا”.

Even in translation, the Arabic makes itself heard, especially when Hashem Beck chooses to transpose it in its most literal sense. For example, in the final section of 3amto (meaning "auntie"), a poem written in the personas of her aunts, the repetition of ya 3uyuni ("oh, my eyes") emphasises the tenderness of this term of endearment:

Allo? Hi ya 3uyuni inti you are

my eyes my eyes my eyes

“[English] is not my voice... This was just how I used English, how I sort of broke English,” she says. “It was a broken English with Arabic words and represented the way I speak. Sometimes it was like a wilful breaking of the English, because that's what I do.”

'I found out that I’m probably kinder to Lebanon in English'

- Zeina Hashem Beck

She decided to experiment further and to explore the boundaries of language and her art. Because her education was dominated by the “language of the coloniser”, both French and English, Hashem Beck admits she feels more comfortable writing in English than in Arabic. Yet she found a way to use this to her advantage, developing a new hybrid form she calls her “duets”.

“The first duet that I wrote… I wrote the entire poem in Arabic first [but] I was thinking about it in English at the same time... I started to try to translate it and then I thought, no, it doesn't work. It doesn't work. That's not it. It's not a translation. They are talking to each other in my head. And they might be saying different things.”

Some of her duets blend the two languages on the same page, with direct translations sitting above one another, and indirect “responses” stanzas apart. At other times, they have been separated so that the English poem sits on the left hand side of the spread and the Arabic on the right.

“I found out that I’m probably kinder to Lebanon in English,” she says. “When you’re outside of Lebanon… you have this nostalgia. Then when you move back to Lebanon, which happens every summer… you start seeing, of course, the little things and you remember, you remember - 'Oh my god, the electricity is off again, for fuck’s sake' - and you’re living the dailiness of it and you're angry with it and you're frustrated because it's not easy, it's not an easy country to live in.”

An ode to Lebanon

When the protests in Beirut first broke out on 17 October, Hashem Beck was backstage at London’s Southbank Centre, having just completed her set at the poetry and live music event, Out-Spoken. As the messages poured in from relatives abroad, she found herself “insanely yelling out” to everyone around her, suddenly aware that she was the only Lebanese person there.

Two days later, Hashem Beck was still in London, preparing for another reading but struggling to concentrate on anything other than the spiralling political events. “[I kept] telling myself: you’re in London, go out for a walk. It’s nice. Be a tourist!

(Video by Zahra Hankir)

“[But] I was stuck – I was physically stuck in the room, pacing – in a very small London room – pacing between the armchair and the bed, opening the curtains and just staring at the London sky.”

She felt an urge to breathe new life into an older poem, and decided to include her Ode To Lebanon in that night’s reading, a poem she originally wrote during the 2016 municipality elections in Lebanon, but with some revisions: the version she read that night referenced footage broadcast the previous day from Beirut:

It is not every day a woman kicks an armed thug in the gut.

It is not every day a city, a country, stretches its limbs and begins

to rise. I give you – I want to say it, goddamn it –

hope - amal, easily turned into pain – alam

We didn’t think we could eat it. But here,

here, it is warm, like bread.

Lately, Hashem Beck says, she has been wanting to move beyond writing about war, and towards topics that are even more personal like motherhood, friendship and love.

But news from home is an inevitable distraction, especially being a temporary resident in the UAE: “There's the always the [question of] how are we going to get back and be able to live in Lebanon? Or do we then really leave and immigrate to a western country?”

The question of whether she identifies as a writer in the diaspora is one that discomforts her: “I don’t know where I am,” she says. “For me, in my head, it’s like I never stayed and I never left. I don’t feel like I ever left. I’m in this liminal place.

“I think it's a question that has sort of opened up ways of thinking about home which is like what my poems do as well. I mean… will I ever be able not to write about Lebanon? No, there is no choice, you know, and that's okay. And that's okay. You know?”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].