Narrative wars: Lebanon’s media take shots at popular protests

While hundreds of thousands of demonstrators have taken to the streets of Lebanon for three weeks, a war is brewing online and on paper to define the protest movement.

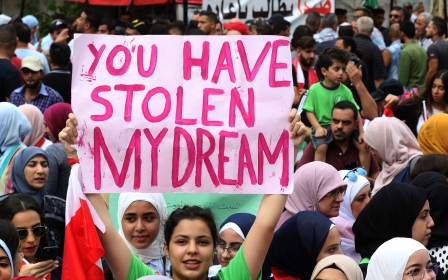

On social media, Lebanon’s protest movement appears a positive, inclusive force holding the country’s leaders to account - as footage abounds of cheering crowds, elaborate murals, and community initiatives.

But local media outlets paint a very different picture, as demonstrators’ calls for an overhaul of the sectarian system that has long governed the country has been portrayed as a dangerous movement backed by foreign powers to drag Lebanon into open conflict.

While disinformation campaigns are not new, the popular uprising sparked on 17 October by socioeconomic grievances has further brought to light the media ecosystem dominated by political parties and politically affiliated ownership.

Contradictory conspiracies

With banks forced to close for 12 days, and schools struggling to stay open, Lebanon’s state-affiliated media channels have spread what many are calling disinformation campaigns about the movement.

Lebanon, a semi-democracy where its 18 officially recognised sects are represented largely proportionally in government, is not shy of conspiracies related to local or foreign powers targeting one sect over another.

However, in a protest movement where barriers within the country’s population have been broken, the extent of these accusations is unprecedented.

Theme 1: Israel and the Gulf states

One theme is dominant in for pro-Hezbollah daily Al-Akhbar’s coverage of the protests: the idea that foreign powers, particularly Israel, are trying to turn the movement from an uprising of the poor into an uprising against the resistance - meaning Hezbollah and its regional allies Syria and Iran.

In a series of articles labelled “the hijacking of the movement”, Al-Akhbar cited unnamed sources alleging that caretaker Prime Minister Saad Hariri admitted to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates of pouring money to local television stations Al-Jadeed, LBC and MTV, in order for them to cover the protests.

In that same article, the paper claimed that Qatar, at the request of Turkey, also financed protesters’ efforts in Tripoli and other parts of northern Lebanon.

Al-Akhbar concluded its series stating that it was “obvious that Israel wants this movement to at least be a restrictive force on Hezbollah”.

Theme 2: USA

Meanwhile, Hezbollah-affiliated Alahed News has claimed that Washington was also interfering in the movement through US academic and American University of Beirut (AUB) professor Robert Gallagher.

Gallagher was filmed speaking at an educational sit-in at the occupied “Egg”, an unfinished brutalist theatre in Downtown Beirut, which has since been used to organise discussion groups, lectures and film screenings.

Gallagher told a crowd that capitalism was the root problem of the country’s woes, called for soup kitchens and other efforts to fill in the gaps of the government, including the formation of local councils.

Alahed News, however, claimed that Gallagher co-founded the Eudemian Institute, which, it said “sells political economy plans” to governments and social movements.

No information could be found online about said institute.

Theme 3: Terrorism

Though the powerful Iran-backed movement has been one of the more vocal parties against the protests, Hezbollah is not alone in its attempts to shape the narrative.

A column on the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) party’s website Tayyar warned that the city of Tripoli - where thousands of protesters continue to take to the streets - could turn into a terror haven, claiming armed groups from Syria’s Idlib province could potentially move there.

Television station OTV, which also belongs to President Michel Aoun’s FPM party, has also routinely questioned the authenticity of the protests.

OTV has cited the distribution of sandwiches and knafeh, the happy atmosphere at some of the demonstrations, and even the fact that some of the protesters are holding new smartphones as deeply suspicious.

Meanwhile, allegations also emerged across social media that left-wing Serbian political organisation Otpor - which shut down in 2004 - was also involved, citing the large fist erected in Beirut’s Martyrs’ Square, somewhat resembling the defunct party’s logo, as proof.

Some protesters have mocked the claims regarding Otpor, noting that many political parties in Lebanon and their campaigns include clenched fists as well.

Backlash

The flurry of allegations over the involvement of conflicting regional powers in the protest movement has been received with derision and condemnation - both by demonstrators themselves and by journalists.

Since the uprising began, four journalists at Al-Akhbar have quit, citing the newspaper’s coverage of the demonstrations.

On 30 October, journalist Joy Slim announced her resignation on social media, saying the daily had “joined the ranks of the counter-revolution” and resorted to conspiracies “as it did” with Arab uprisings elsewhere.

Others followed suit, including the editor of Al-Akhbar’s economic supplement Mohammad Zbib, and journalists Sabah Ayoub and Viviane Akiki.

When announcing her resignation on Tuesday, Akiki cited the newspaper’s “professional conduct in covering the popular uprising” and “for other reasons related to its journalistic conduct, which has not been taken care of to this day”.

Meanwhile, Lebanese protesters have pushed back against the accusations of foreign interference, notably by launching a campaign called “I am funding the revolution” - with men and women repeating this line in a widely shared montage video.

Crowd funding

While some local protesters and organisations, such as the independent Sabaa Party, have funded some elements of the demonstrations, such as stages and sound systems, many of the initiatives of the past few weeks have been carried out by volunteers.

Protesters often spontaneously donate boxes of water bottles and food, and those who are trained in first aid and other services have volunteered their time.

Community kitchens have been run by several cooks pro bono, while protesters currently on strike - notably including university professors and students - have taken the lead in supporting and coordinating efforts.

Though groups such as the Sabaa Party have chipped in on entertainment, the logistics of maintaining the protests largely rely on a network of volunteers.

Hezbollah in the crosshairs?

While many of Lebanon’s political parties have spoken out against the protests, Hezbollah has taken the demonstrations particularly personally.

In Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah’s second speech since the beginning of the uprising on 27 October, he said the protests were no longer an independent and depoliticised movement targeting socioeconomic grievances and rights.

“Several sides are exploiting popular protests to settle their account with Hezbollah and implement foreign agendas,” he said. “We have information that an anti-resistance scheme is being prepared for Lebanon.”

Nasrallah added that political and foreign powers were “using some of the squares to describe the resistance as terrorists and to also take aim at the resistance’s weapons”.

To many protesters, such a sentiment would not ring true. Hezbollah’s weapons, long controversial in some Lebanese and international circles, have been an afterthought at best in demonstrations primarily about economic and political grievances.

While some chants have targeted Nasrallah and Hezbollah as a whole, no songs have singled out the movement’s weapons, and the Shia party has been treated by protesters like any other political force in the country - a relatively new development.

The protesters’ denunciation of Hezbollah comes as the party has cemented itself in Lebanon’s political mainstream in recent years.

With three ministers in the now-resigned government and 13 members in parliament, Hezbollah is seen as part of the political elite - and this shift is now having consequences.

Nasrallah’s name has joined the list of Lebanon’s leaders whom protesters are calling to be removed, with people in Beirut chanting “Neither Hariri nor [Gebran] Bassil will separate us, neither Nasrallah nor [Walid] Jumblatt will separate us”.

Political hijacking

In addition to accusations of foreign intereference, another narrative pushed by Lebanese media outlets and political leadership alike is that the uprising has been hijacked.

Some commentators, including those in the anti-Hezbollah Annahar newspaper, have claimed that the protest movement has been hijacked by “rioters” to destroy its otherwise peaceful nature.

More significantly, reporters, political pundits and others have said that the vast majority of protesters have been “misled” by political parties.

Hezbollah MP Hassan Fadlallah in particular has accused the Lebanese Forces (LF) party of infiltrating street mobilisations, citing its rivalry with the FPM.

There have certainly been attempts by some political parties, particularly those in the semi-defunct 14 March movement aligned with Western powers, to claim the movement as their own.

On 19 October, four LF ministers resigned, suddenly calling for the downfall of the government.

Following the resignation of Hariri and the LF ministers, Fares Souaid and other leaders of the 14 March coalition have started to speak up in support of the popular uprising, targeting political rivals, Hezbollah and the FPM.

However, protesters appear aware of these attempts to coopt the movement, prompting calls to reject those who have long been part of the elitist political system.

In a column on independent media Daraj.com, editor-in-chief Hazem al-Amine called to “protect the Lebanese uprising from Hariri, [Lebanese Forces leader Samir] Geagea, and [Progressive Socialist Party leader Walid] Jumblatt.”

In another editorial, organiser and researcher Nizar Hassan added that it was a priority to prevent outsiders, notably political parties, from coopting the movement.

Media disinformation

Media researcher Azza el-Masri told Middle East Eye that disinformation campaigns were used to play with Lebanese citizens’ emotions at a time of uncertainty.

“This is not a new trend at all,” Masri said, adding that a lot of disinformation starts through voice notes, messages, and media sent through WhatsApp.

'We’ve been trained for the last 30 years to be complacent toward an oppressive sectarian system'

- Azza el-Masri, media researcher

For Naser Yasin, a political analyst at the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs, the increased volume of disinformation campaigns is evident given that the emergence of the country’s largest popular movement in nearly 15 years came as a shock for many.

“I think those in power were surprised by the uprising,” Yasin told MEE, describing some of these campaigns on both social and traditional media as “orchestrated”.

Masri also believes that the Lebanese media plays a role in perpetuating and even building disinformation campaigns.

“We’ve been trained for the last 30 years to be complacent toward an oppressive sectarian system,” Masri said.

“The Lebanese media has always been the media of the political elite… and even if it represents itself as taking the side of the people, it is still bankrolled by those in power and those sectarian warlords we’re trying to rid ourselves from.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].