The Olive Trees' Jazz: Algiers poet speaks in music of the senses

The Olive Trees' Jazz and Other Poems opens by posing an urgent question about identity and language.

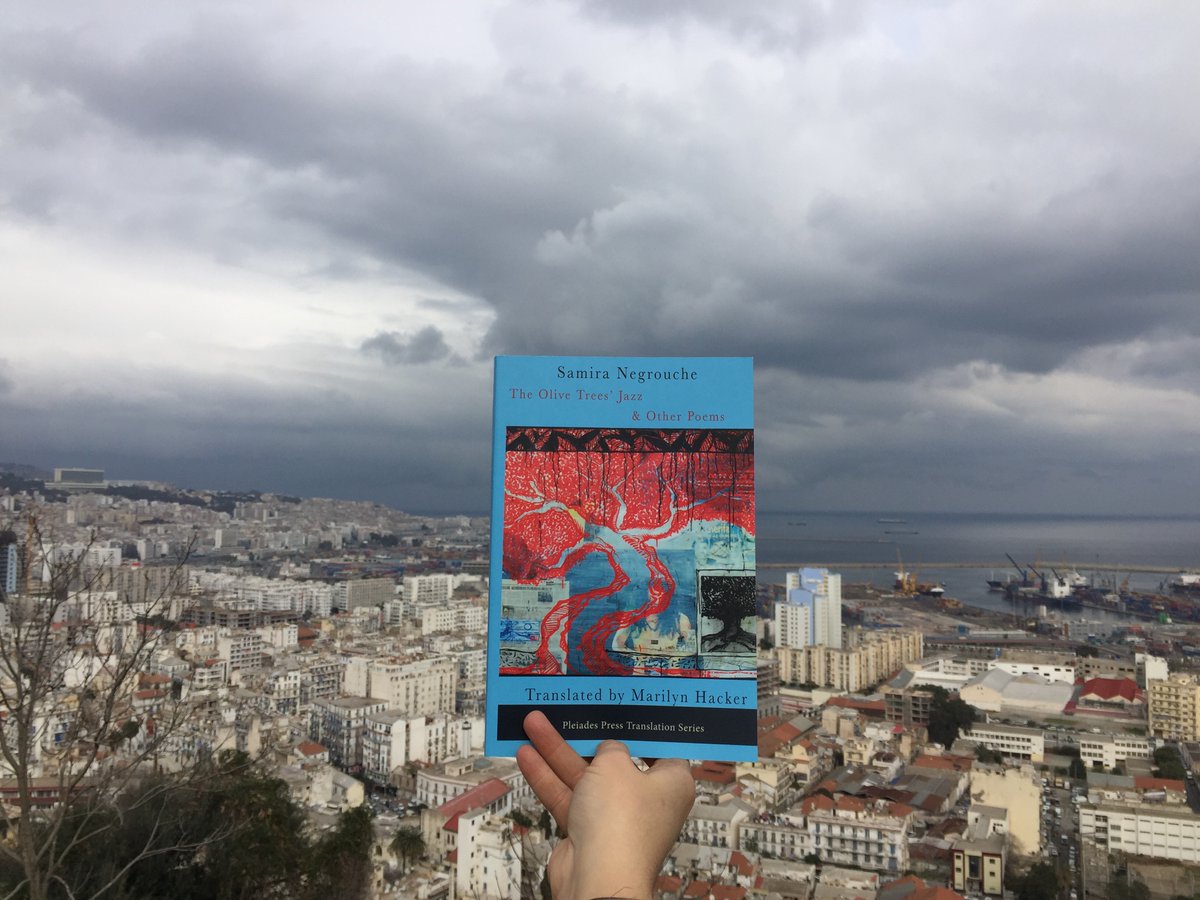

The bilingual poetry collection - with French poems by Algerian poet Samira Negrouche and English translations by Marilyn Hacker - arrives this month from Pleiades Press, and its first work blurs the lines between essay, manifesto, open letter, and prose poem. In “Who is speaking,” the poet-narrator seizes the reader by the shirtfront and asks: “Tell me - Who are you? When you speak in someone else’s language?”

Negrouche (born 1980) lives in Algiers and writes in French, and she has surely heard this question many times. She wrote this particular poem, she says, “at a time when I felt I needed to resist being in reaction.” Instead of answering the question of why she doesn’t write in Algeria’s other languages -Modern Standard Arabic, Algerian Derja, or Tamazight - the poem reflects it back out at the reader.

Deftly, this initial work sets the terms for our engagement with Negrouche’s collection, her first to appear in English translation. Some French or English readers might think of themselves as neutral, just as “Water seems neutral,” the poem tells us. But Negrouche - who trained as a doctor but has shifted to the arts - explains why this is not so. “The most neutral seeming chemical entity carries within its structure the most complex memory, complex because invisible, unsuspected.”

The poem also reflects back the statements of a range of violently “neutral” readers:

You speak French very well...are you an independent country after all?...the language of the colonizer...an authentic poet of your region would write in Arabic...you’ve got to speak to the people...you are dubious and don’t represent the citizen lambda...all the Algerian writers live in Paris...you are trilingual illiterates...an Algerian novel is a novel whose French has a tan...

These unintentionally tragi-comic readers make it hard for the poet to publish. “The hardest thing", the poem tells us, is "to struggle beneath a gaze sure of its neutrality, its benevolence.” And the worst sort of reader, it continues, is one who has “a clear conscience; that ethnologist’s point of view in search of authenticity[.]”

The poem asks us, in essence, to read better. It asserts: “Who does not listen to them attentively does not listen at all.”

It was the publisher’s decision that the poems should appear in both languages, but Hacker says she was delighted with the choice. “Samira’s books in French were published by small presses, in Algeria or in France, and it may well be easier to find her work in French in this edition. At the same time, I think, or I hope, that the translations stand on their own as poems.”

In the 16 poems that follow, in French and in English, the reader is left to their own devices. Yet hopefully, we can all move through the collection with less of a “clear conscience” / “conscience tranquille”.

‘To rise as one multiple’

Translator-poet Hacker writes, in her introduction to The Olive Trees’ Jazz, of several meetings with Negrouche over the last decade. The first came in 2011, when Negrouche’s "Sept petits monologues de jasmin” appeared in Hacker’s inbox with a request to translate it for Banipal magazine.

This short prose poem, Hacker says, “was like nothing else, in its multivocalism, in its sensory evocations, in the way it walks a line between the dramatic monologue, plurivocal, and the lyric, in the sometimes difficult confines of the prose poem.” The poem shifts between registers in an almost dizzying manner, as here, in the "Damascus" section:

Holy man of the fertile valleys a bicycle rolls across the heart of your wisdom and now the Heights are merely firing ranges.

Nine years after their first encounter, “Seven Little Jasmine Monologues” now appears in this new collection, which brings together poems from four of Negrouche’s books: In the Shadow of Grenada (2003), The Olive Trees’ Jazz (2010), Six Makeshift Trees Around My Bathtub (2017) and Quai 2|1, A Score on Three Axes (2019).

The poems in this new bilingual edition don’t follow a chronological timeline. Hacker said that, as she was putting it together, she decided to choose from among several collections, rather than translate one in its entirety, because, she says, “there is such variety in Samira’s work, from the lyrical to wry analyses of human interaction to the painterly, with the temptation of abstraction: I wanted this collection to represent it”.

Political realities have changed in the seven cities since Negrouche wrote her jasmine monologues, particularly in Cairo, Damascus, and Sanaa. Yet the work keeps its freshness by focussing less on the particulars of 2011 and more on the contradictions that lay beneath the soil of revolt, as in the “Rabat” section where:

…at the height of virtuous feelings small-time monarchs of a cobbled-together celebration a mother on holiday sipping orange juice at nearly midnight a mother finds the smile of the plucky child beautiful the smile of the little girl who on the square at nearly midnight is selling a packet of tissues to the mother whose children are already asleep already dreaming…

By now, Negrouche tells MEE, “it seems we have learned a lot from the so-called Arab Spring. Putting a group of countries in the same storyline didn’t tell enough about the complexity of the situation.” Current protest movements around the world are intensely individual, much as they appear in “Seven Little Jasmine Monologues.” And yet, Negrouche says, “there is an urgency to understand more of who we are as a collective, and why it is important to rise as one multiple.”

“Seven Little Jasmine Monologues” ends in the poet’s hometown, Algiers, calling for a new train line “from Tunis to Alexandria and from Beirut to Istanbul”. This call seems not just about facilitating free movement, but also about the free exchange of aspirations.

Collaborating with other artists

Although Negrouche does not shy from political expression, she is perhaps best known for her collaborations with other art forms. The poem “Variations on a minor third” came from joint work with the Greek musician Angelique Ionatos, while the collection Quai 2|1 emerged from a project with musicians Bruno Helstroffer and Marianne Piketty.

Negrouche’s collaborations with the poet Zoe Skoulding led to the production of an electronic sound collage, while her poetry has also reflected on art, as in the catalogue Waiting for Omar Gatlato: A Survey of Contemporary Art from Algeria and Its Diaspora.

Some of the poems in The Olive Trees’ Jazz bring together an intense, painterly visuality with a gesture towards music, such as in “Halt II,” which begins by following a stray air bubble’s path to “a white lake/ at the heart of summer/ smile on your lips/ its curve barely/ warm.”

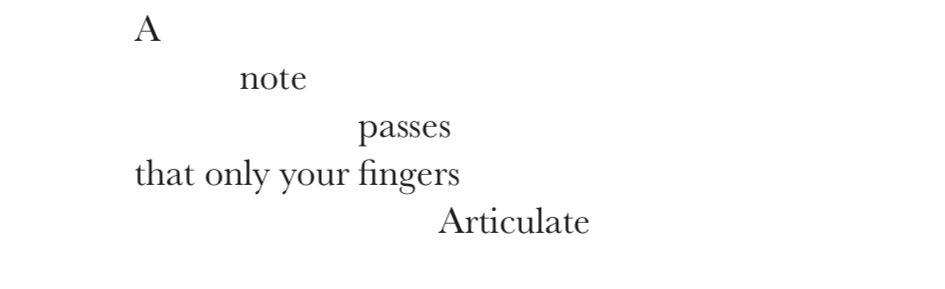

The lake sits beneath the July sky, “in a silence/ of mountains” in a scene that feels as much like an oil painting as a vibrantly hot summer day. But, at the end, the poem shifts suddenly into a sonic register:

Here, the music is seen but not quite heard; it’s held in a space between the senses.

“Music and visual arts are a way to question my language, to transform its logic, to move lines I forget to think about,” Negrouche said. “It isn’t that easy and natural to work with someone else, but the admiration and the excitement sometimes make it possible.”

These collaborations, she says, are a way to “explore the impossible” between herself and other artists.

Poetic ancestors

In her introduction to The Olive Trees’ Jazz, Hacker gives a brief overview of Algerian Francophone poetry from the mid-20th century to now, and then focusses in on Negrouche’s poetic ancestors.

Two Algerian literary “fathers” haunt the book: the poet Jean Sénac - murdered in 1973, in what was just as likely a political assassination as a homophobic one - and the poet Djamal Amrani, tortured and then exiled during the Algerian war, who wrote the account of his ordeal before re-establishing himself as a poet, in Algeria.

Hacker recalls Negrouche’s relationship with Amrani as a “poetic apprenticeship,” while Negrouche explains: “I first met Djamal Amrani at an art exhibition when I was twenty, when my first collection was just published. He said he was happy I mentioned him in a radio interview and that he was happy to know I exist.”

That meant a lot, Negrouche said, particularly at a time when the “black decade” of the 1990s Algerian civil war still hung heavily in the air “and cultural life was very slowly birthing from the ashes”.

The poets met again two years later. Negrouche said that she had been struck, as a teenager, by the deaths of so many Algerian poets - Tahar Djaout, Youcef Sebti, Jean Senac, and others - and so meeting Amrani “reconnected me to a part of Algeria I needed to see and imagine alive”.

Negrouche’s “Memory of a Father” is dedicated to Amrani, and it has “farewells one does not want to/utter/ that one never knows how to/ pronounce.” Both this poem and the whole collection are in dialogue with a host of predecessors. The first poem asks: who speaks for the ancestors?

And while Negrouche writes in French, the ancestors who underlie these poems speak in Arabic and Tamazight, Greek and Latin. Perhaps, if we listen carefully enough to Negrouche’s poetry, we will be able to hear the thousands of poetic voices that came before.

The Olive Trees' Jazz and Other Poems by Samira Negrouche is translated from French by Marilyn Hacker and published by Pleiades Press in the US.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].