The Hirak transformed Algeria, but not the system

In 2019, Algerian prisons welcomed big names: former prime ministers Abdelmalek Sellal and Ahmed Ouyahia; former intelligence chiefs Mohamed Mediene and Athmane Tartag; and Said Bouteflika, brother of the former president Abdelaziz Bouteflika.

To this list, we must add a former head of police, a dozen ministers and army officers, the heads of the four main parties that supported Bouteflika, and some of the richest people in the country. Let’s not forget the fugitive ministers.

An impressive journey

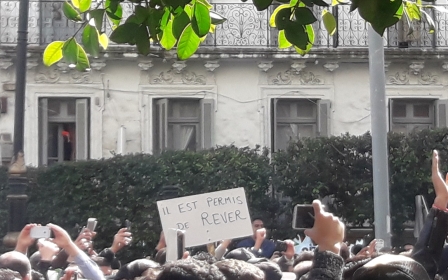

Indeed, the country’s former powerbrokers have been neutralised by the Hirak movement. On 22 February 2019, millions of Algerians took to the streets, launching a rare, non-violent process to get rid of the leaders in place. But upon the first anniversary of the uprising, Algerians are not sure what to think.

The old, blind regime's insistence on maintaining an impotent president pushed the public to explode in anger

The colourful and peaceful protests last spring, which drew in all generations and social classes, were so powerful that Algerians thought anything was possible. But since then, frustration has emerged among some who believe that there is still a long way to go, or that the movement has reached a deadlock.

Algeria’s journey so far is already impressive. Not only did the protesters get rid of public and military figures from the old regime, but they also got Bouteflika to resign after he vowed to run for a fifth term. The old, blind regime’s insistence on maintaining an impotent president pushed the public to explode in anger.

The army has also regained its composure, cleaning up its act by prosecuting dozens of corrupt officers and committing to fight corruption without bloodshed.

Reinventing politics

The fact that protests have been peaceful has contributed to this shift within the army. Algerian people have found out that it is possible to protest peacefully and with joy; previously, social protests have ended in violence and attacks on public buildings.

Skilled and social-media-savvy protesters have shone a positive light on the Hirak, showing mundane acts of kindness - letting an ambulance pass through, or helping a disabled person - to bolster national solidarity, pointing to new norms and values. Until this point, Algerians had been rendered powerless by the old, corrupt regime. The Hirak gave them fresh momentum.

They started to talk about politics again. Youth, who had been disengaged from politics, started debating everything from the constitution to the transitional process. At family gatherings and coffee shops, traditionally symbols of idleness, politics began trending. Algerians truly started to believe that they could be a part of their country’s history.

Algerians believe this even more now that the culture of impunity has ended. The barons of the old regime have fallen, a result of the new military strategy, which included pushing Bouteflika to resign. Neutralising the financial power of the oligarchs was vital to avoid a setback.

Last December, the Algerian people were able to witness firsthand how corrupt their government had been, during the trials of Sellal, Ouyahia and several other ministers. Yet, despite all the upheaval, many Algerians remain sceptical.

Activism of old networks

Indeed, the networks that were around during the Bouteflika era have not disappeared all of a sudden. They remain active in the media and online. As many former ministers and regime figures know they could be indicted at any time, it is safe to say that they are not waiting around doing nothing.

There are also other, more worrying aspects, including the fact that Algeria has not been able to move towards a meaningful political solution after a year of popular contestation that freed its citizens, parties, army and other political actors.

Despite this void, no party has been created over the past year of protest, even though it could have flourished under such circumstances

Algeria’s failure to offer something new was confirmed during the presidential election in December: only five candidates were able to run, and four were former Bouteflika ministers, while the fifth built his whole career around the old regime. Abdelmadjid Tebboune, elected under contested circumstances, was Bouteflika’s prime minister.

This shows that even though the popular protests got rid of most political leaders, they did not allow for the emergence of a new political class, despite the fact that the Hirak was yearning for new, young leaders. Some leading Hirak figures were in favour of participating in the presidential election, but they did not dare express this, fearing the wrath of other activists.

Activists’ distrust of politicians has led to a paradox. The political field is in ruins. Despite this void, no party has been created over the past year of protest, even though it could have flourished under such circumstances.

Accusations of treason

On the first anniversary of the protests, a group of activists with diverse opinions started to emerge, in order to organise the Hirak. But this is an impossible bet: these are the same people who fire accusations at everyone. They will become victims of the same allegations of treason that they are so quick to pin on others.

Algeria also remains far from a democratic model. The army remains at the heart of the power structure, and the December election was not conducted fairly, even if the candidacy was theoretically free and the chances of fraud on voting day were technically very low.

Ironically, the vote was distorted by two converging factors. On one hand, the army wanted a presidential election at all costs before the end of the year, which caused dangerous tensions, and close to zero participation in Kabylie. On the other hand, a fringe of the Hirak put forth enormous pressure to undermine the election, risking unknown consequences.

To what extent did this fringe of the Hirak act out of democratic concern, and to what extent was it manipulated by the old regime networks, for whom getting rid of army chief Ahmed Gaid Salah was essential? It is hard to say. But as a result, Tebboune suffers from a strong suspicion of illegitimacy.

Algeria’s governance remains weak and confused, with no guarantee that authorities are learning from the excesses of corruption, or considering enacting mechanisms capable of eliminating it.

Faced with those who demand everything immediately - media freedom, judicial independence, free and fair elections - the country has not yet produced a voice capable of saying that this is a process we can build together, on a permanent basis.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article has been translated and condensed from the MEE French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].