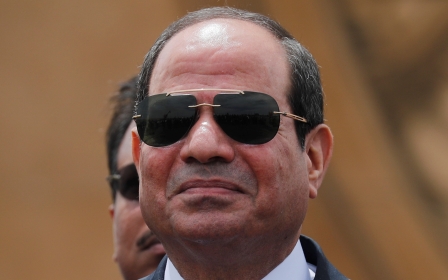

Egypt: Sisi is using human rights defenders as a bargaining chip

Egypt’s crackdown on members of the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR) forewarns of a second wave of branding civil society work as “terrorism,” in a bid to silence the last remaining independent human rights activists in the country.

Rights groups in Egypt are distinct from the rest of civil society due to their administrative and financial autonomy, which has made them a target for successive regimes since the human rights movement blossomed in the 1980s. While the Mubarak regime tolerated these groups at the same time as deliberately limiting their work through administrative obstacles, the Sisi regime has unleashed a policy of prevention, arrests and direct threats.

The measures against rights groups unveiled since 2014 have been partly aimed at gauging the reaction of the international community

In recent decades, the clearest clash between human rights organisations and the Egyptian state came amid the rise of the military’s role in political life after the 2011 revolution. The military adopted a trial-balloon approach in suppressing rights groups, with the crackdown initially targeting lower-profile organisations before moving on to more prominent ones, such as EIPR.

On Thursday, EIPR announced the release of its advocates Gasser Abdelrazek, Karim Ennarah and Mohamed Basheer, but it was not immediately clear if they were still facing charges.

The escalation against EIPR, however, was not a surprise to the human rights community, including myself. It is consistent with gradual legislative, political and administrative measures taken by President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s regime since 2014. Our colleague, Gasser Abdelrazek, is not the first human rights defender arbitrarily accused of terrorism, nor is EIPR the first organisation accused by the regime of being a terrorist group.

Two years ago, for example, the executive director of the Egyptian Coordination for Rights and Freedoms, Ezzat Ghoneim, was arrested, followed by the successive arrests of the group’s board of directors. Both campaigns employed the same tools, including the “terrorism” designation.

The current clash between the military and human rights groups has its origins in February 2011, when rights groups played a leading role in highlighting violations against protesters during the anti-Mubarak uprising. Military police raided the offices of the Hisham Mubarak Law Center and arrested around 30 human rights defenders, lawyers and journalists. Others were arrested for bringing blankets to demonstrators in Tahrir Square.

This marked a declaration of intent from the military regime, signalling its future policy towards human rights groups. It has since worked to curb their expansion.

Tightening the screws

After the military regime overthrew Egypt’s democratically elected government in 2013, it deliberately moved from the phase of threats and arrests to blatantly treating human rights defenders as “terrorist” groups, in the same way it dealt with the opposition Muslim Brotherhood. That year, the funds of more than 1,000 religious charities were frozen.

The military regime later took other steps to tighten the screws, including legislative amendments that facilitated the arrests of activists and journalists.

The measures against rights groups unveiled since 2014 have been partly aimed at gauging the reaction of the international community - particularly, those countries that pay lip service to human rights issues in Egypt while maintaining a strategic partnership with the regime.

Egyptian authorities would then take steps to reduce tensions and provide legal cover to the state, including through administrative decisions against civil society.

The Egyptian regime has simultaneously sought to placate the international community and divert its attention from human rights issues with lucrative economic and military deals. The EIPR arrests, for example, were preceded by Sisi’s meeting with a top EU official in Cairo, where they discussed strategic relations, including the Libya crisis, migration, refugees and the economy. The subject of human rights in Egypt was not on the agenda.

Mobilising the world

The Sisi government is thus holding rights groups hostage to its diplomatic relations with the international community, seeking to reduce demands for political and legal reforms to a list of individuals to be released in exchange for temporary political gains.

The only way out for the two sides in this asymmetric relationship with the Egyptian regime - human rights defenders on the one hand, and the international community supporting them on the other - is to mobilise international pressure against the regime.

This could be carried out in several ways. First, by working to characterise Egypt as a state that does not abide by global human rights agreements; second, mobilising international opposition to Sisi’s policy of using military and economic deals as bargaining chips in exchange for turning a blind eye to his human rights abuses; and third, opposing the regime’s policy of terrorising civil society groups with its politically motivated “terrorism” label.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].