Egypt: Sisi has squandered the chance to reconcile with the Muslim Brotherhood

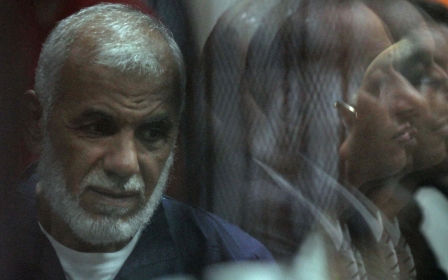

On Monday, Egypt’s highest appeals court upheld the death sentences of 12 Muslim Brotherhood members, including two senior leaders.

A 2013 military coup eliminated the Brotherhood from political and public life, shortly after it won free and fair elections that followed Egypt’s 2011 democratic uprising. The Brotherhood’s political party was subsequently banned, the group was declared a terrorist organisation, and many thousands of its members and supporters were either killed in massacres or arrested for protesting against the coup.

Monday’s court decision was widely condemned by human rights groups, who highlighted the absurdity of the 2018 mass trial that led to the original death sentences. The men were convicted of violence at Rabaa and Nahda squares, the primary sites of anti-coup protests.

The recent court ruling closes the door, at least for the time being, on any possibility of national reconciliation in Egypt

The absurdity of the 2018 trial was not lost on human rights groups and political analysts, who highlighted that it was Egyptian security forces - not Egyptian protesters - who were the primary instigators and perpetrators of the August 2013 violence.

On a single day, 14 August 2013, around 1,000 Egyptian anti-coup protesters were killed by security forces at Rabaa and Nahda. A yearlong investigation by Human Rights Watch suggested that the Brotherhood-led anti-coup protests were “overwhelmingly peaceful”, that security forces may have been “shooting to kill” unarmed protesters, and that the massacre was ordered at the “highest levels” of the Egyptian government.

'Tool of repression'

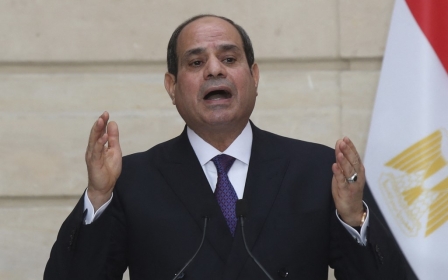

This week’s court decision to uphold the death sentences against apparent victims of violence underscores several things. Firstly, it provides further evidence of the extent to which Egypt’s judicial system is under the control of the country’s top executive, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi.

The International Commission of Jurists has called the Egyptian judiciary a “tool of repression”, while the judicial system has also been widely condemned by the United Nations, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, among other entities.

Secondly, the recent court ruling closes the door, at least for the time being, on any possibility of national reconciliation in Egypt. If anything, it suggests the regime is willing to dig in its proverbial heels for the long-term.

Still reeling from a small but effective anti-government protest movement led by Mohamed Ali, an exiled businessman, as well as disastrous efforts to contain the Nile River dam crisis and manage the Covid-19 pandemic, the Sisi regime continues to feel political pressure and at least some level of political threat.

Clearly, Sisi has determined that the Brotherhood represents too great a threat to be given an opening, even one as tiny as a small-scale prisoner release.

Thirdly, the ruling highlights key differences between Sisi’s domestic and foreign policy calculations. Since the start of this year, the Egyptian regime has engaged in acts of previously inconceivable regional diplomacy with three entities it has consistently accused of being part of a regional terrorist network determined to destroy Egypt: Qatar, Turkey and Hamas.

In January, Egypt, along with Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain, agreed to end the four-year blockade against Qatar. Sisi and Qatar’s emir will likely exchange diplomatic visits later this summer; Qatar will play a key role negotiating on Egypt’s behalf in the Nile River dam crisis; and Egypt’s foreign minister recently appeared on Al Jazeera, the Qatar-based network his ministry had previously cut off and claimed was an ally of terrorists.

Sudden policy shift

In May, Egypt advanced a rapprochement with Turkey, a nation it had long accused of sponsoring terrorism and being a haven for the Muslim Brotherhood, which Egypt declared a terrorist organisation in 2013.

In June, the Egyptian government met cordially with leaders from Hamas, which was declared a terrorist organisation by an Egyptian court in 2015 and has been accused of carrying out deadly attacks inside Egypt.

On the surface, the sudden shift in policy seems shocking. The reality, though, is that it was only a matter of time before these kinds of changes were likely to become necessary.

Egypt takes its foreign policy lead from its Gulf leaders and financiers, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The Saudi-led axis wasn’t able to take advantage of the Trump presidency in the US to the extent that it expected to, and battles against Qatar, Turkey and Hamas were costly and didn’t go as planned.

When it became clear the Trump presidency was ending, reality set in for this axis, and for Egypt in particular: having relations with Qatar, Turkey and Hamas would be less costly than fighting them.

Each country in the axis can now recalibrate its foreign policy based on some reference to its own internal dynamics. In Egypt’s case, it can now stop pretending that Turkey, Qatar and Hamas are terrorist entities or part of an organised global Muslim Brotherhood network.

Future implications

The future ramifications of these diplomatic shifts for Egypt’s foreign policy are significant, but straightforward and simple enough to understand. The implications for Egypt’s domestic policy may be less clear.

The aforementioned diplomatic inroads, along with a renewed, outward US government emphasis on human rights in the Arab region, led many - including me - to believe that the time was ripe for at least a small-scale reconciliation between the Egyptian regime and the Muslim Brotherhood.

Sisi could have presented himself as a benevolent figure, willing to forgive even his most hated political rivals

In fact, the changing political environment made it feel as though it may simply be a matter of time before the Sisi regime would acquiesce to the longstanding demands of human rights groups and allow some key, elderly Brotherhood figures out of prison. If Egypt was willing to make peace with Brotherhood allies in the region, including those it officially considered terrorists, didn’t it arguably make more sense that the Sisi regime would come to an understanding with the Egyptian Muslim Brothers?

After all, reconciliation with the Brotherhood wouldn’t cost the regime much - all that may have been expected was the release of mostly elderly, politically impotent prisoners from jail.

Given the legal framework the regime has created since the coup, Sisi would seem to have little to worry about, particularly if released prisoners agreed, as others before them have, to remain out of public life.

Moreover, there wouldn’t likely have been any pushback from the Egyptian masses or media. The Egyptian regime effectively controls public discourse, as evidenced by its recent orchestration of a more-or-less celebratory climate in the midst of renewed diplomacy with Turkey, Qatar and Hamas, entities previously condemned in Egyptian media as mortal enemies.

Missed opportunity

The benefits to the regime, meanwhile, could have proven significant. At a minimum, Egypt would have scored points with the Biden administration and human rights groups. More substantively, Sisi could have presented himself as a benevolent figure, willing to forgive even his most hated political rivals.

Such an event wouldn’t have been an indication that Egypt was making a democratic turn. Egypt is too mired in authoritarianism for any such delusions. But freeing prisoners would have, at least, been a relief to political prisoners, their families, and human rights advocates.

It could have also paved the way for the return home of some Egyptian media, academic, legal and political figures currently in exile in Turkey and Qatar. But at least in the short-term, it no longer appears that any such move is likely, or even possible.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].