'I'm not afraid to pick a fight': Mohammed el-Kurd on Rifqa, God and Palestinian resilience

Together with his sister Muna, Mohammed el-Kurd was one of the most widely broadcast Palestinian faces during the uprising sparked by Israeli settler attempts to appropriate their family home in the Sheikh Jarrah neighbourhood in occupied East Jerusalem.

The 23-year-old twins’ fluency in Arabic and English, combined with their adept use of social media, made them the go-to source for information about Israeli expansionism in Jerusalem and emblems of the continuing impact of colonialism seven decades after the initial expulsions of Palestinians from their homeland by Zionist forces.

For Mohammed, attention to the family’s plight also brought to the fore his works as a poet, and his credentials as a writer were further established when The Nation made him its Palestine correspondent in September.

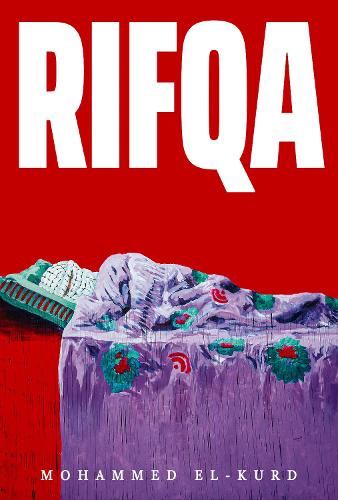

With an entry into the Time 100 list for 2021, an honour he shared with his sister, el-Kurd intends to see the year off with his debut collection of poems - Rifqa.

“For my grandmother, Rifqa El-Kurd, and all of those who are unafraid,” the work begins, setting the tone for what follows: a bold and unabashed tribute to those who resist, past and present.

For now, el-Kurd tells MEE that Palestinian poetry, by the context of its production, is something that by its nature is often strongly imbued with the themes of courage, resistance and pain.

“There should come a time when we are allowed to revel in something beyond that,” he says.

“We are living in colonial times. There is no room yet for ‘post’ colonial literature while we are living under the coloniser.”

'We are living in colonial times. There is no room yet for ‘post’ colonial literature while we are living under the coloniser'

- Mohammed el-Kurd

The writer and poet considers postcolonial theorists among his influencers but his humility forces him to keep a distance when it comes to making direct comparisons. Instead he says modestly that his hope is for his work to serve a purpose and to have an impact.

He explains that the literary figure that most left their mark on his development as a writer and thinker is Rashid Hussein, a late Palestinian writer who wrote Refugee God, a satirical poem that lays bare the bitter reality of the Palestinian plight.

Part of the poem reads:

You wanted me desperate, so that I might live without diversion

You call out: “You are nothing but the scraps of a nation”

Living scattered among caves. Stay put there!

(Elliot Colla translation)

According to el-Kurd, Hussein offered his people: “The political agency of ridicule and satire.”

He adds: “This was perhaps the poem that was most influential to me in my upbringing because it made me understand how writing could be an impactful tool.”

Frantz Fanon, Ghassan Kanafani and Audre Lorde are also listed among his influences.

A continuing displacement

Although literary influences play a part in el-Kurd's poetry, his lived experiences as a Palestinian and those of his disposessed ancestors are what guides his writing.

His late grandmother, the eponymous Rifqa, who passed away in 2020, is the binding force behind his debut collection.

In the poem Rifqa, el-Kurd conveys not only his grandmother’s personal experience of the Nakba but the dissolving of her narrative into the greater story of Palestinian loss. A native of Haifa, Rifqa was chased from her home and became a refugee overnight.

Given the continued dispossession of Palestinians and el-Kurd’s own struggle against Israeli settlers trying to appropriate his Jerusalem home, the privilege of historic detachment is denied the poet when recounting her story.

El-Kurd writes:

The morning of a red-skied May 1948 / Could’ve been today. / They knocked the doors down /claimed life as their own

And as the pain of dispossession lives on through generations, so does the hope of return, which el-Kurd expresses through the symbolism of the Palestinian key.

Another part of the poem reads:

She walked solid. / ‘We’ll return once things cool down’ / and she believed / wore her key / until her key her neck her memory / became the same color.

Since 1956 the Rifqa family has lived in the occupied East Jerusalem neighbourhood of Sheikh Jarrah when they were given a home by UNRWA and the Jordanian government.

After the 1967 conquest of the entire city by Israel, settler groups have launched a campaign of appropriating Palestinian homes and land in the neighbourhood.

The el-Kurd family home has been the frontline of these attempts for years and in one viral video, Mohammed’s sister Muna is seen confronting a settler who protests: “If I don't steal your home, someone else will steal it.”

Such flagrant absurdities are packaged into verse, recounting the family's experience.

Invaders came back once again, /claimed the land / with fists / and fire / excuses / beliefs / of the chosen and the promised / as if God is a real-estate agent.

The verses also reveal the influence of Mohammed’s mother Maysoon Abu Dweih el-Kurd, who is, like him, a poet.

In one of her works, she writes:

I am Sheikh Jarrah. / There’s a spear in my waist / and spears in my back. / My resilience is an edifice. / I am Jerusalem’s northern gate

Despite the shared themes of resilience and determination to take back what is theirs, where the two diverge is in choice of language. While Maysoon writes in her native Arabic, Mohammed prefers English.

On writing in English

There is a utilitarianism underlying el-Kurd the younger’s decision to use English as his preferred medium, one rooted in his stated desire to have an “impact”.

“I feel like the Palestinian people are so under- and misrepresented in the English language,” he tells MEE.

“We get talked about as if we’re not there and we get talked about without any political agency.”

Without claiming to speak for all Palestinians, the poet says he feels the need to write about Palestine in a way that he thinks is authentic to what Palestinians are demanding.

What is important, he argues, is the need for Palestinians to establish a new era in writing and break from a pattern of victimisation and the need to humanise themselves in order to elicit sympathy from an international audience. The onus to acknowledge their humanity must never be on themselves.

'If you can’t see Palestinians as humans, then the problem is with you'

- Mohammed el-Kurd

“If you can’t see Palestinians as humans, then the problem is with you. It’s not with Palestinians’ lack of humanity - it’s because you’re racist.”

As a result, Rifqa is not a book that sets out to make the reader feel sorry for Palestinians but instead casts them as agents with the potential for their own future liberation.

He says: “If I need to bring my young sister in here and display [her] misery, fear or panic for you to sympathise with Palestinians, then I am the one being problematic.

“The main issue at play isn’t humanity or lack thereof, it’s the fact that we’re constantly talking about victims and we don’t dare spell out who the villains are causing these victims.”

The role of God

El-Kurd’s mission is for Palestinians like himself, to write on terms set out by themselves, and one aspect of this drive that is clearly present in Rifqa is an evident religious influence.

He is keen to stress that the Palestinian question is not and never was a religious one but rather a colonial one. Nevertheless he recognises the healing potential of faith (of any kind) for the Palestinian people and wants to push back against a literary scene that is often defined by a secular worldview and a total absence of faith.

He writes about God, the Quran and his spiritual beliefs, without feeling the need to hide behind metaphors or caveats.

In the poem "Smuggling Bethlehem", which he calls one of his “favourite” poems, he talks about how his mother would tell him to recite verses from the Quran when they approached military checkpoints.

The elder el-Kurd would buy fruit and other goods from the occupied West Bank city of Bethlehem and would hide the produce in the family vehicle intent on avoiding the fines if they were found by Israeli soldiers.

The verse of the Quran, el-Kurd recites is the ninth verse of the 36th Surah, called Yasin. Included in the poem, it reads: “And We have put before them a barrier/ and behind them a barrier/ and blinded them, so they do not see.”

As a young boy, Mohammed attributed the Israeli soldiers’ failure to find the goods to the protection provided by the verse.

“That poem is the truth,” el-Kurd explains, “and that really helped me as a child believe in some kind of power I held.”

He continues: “I think religion has played a very important role in consolation when it comes to the Palestinian people. I don’t think the Palestinian people would have been able to survive as long as they have if it had not been for faith.

“We die constantly and we are killed constantly. And those of us who are mourning need answers. We need to be able to cling to the idea that those who were killed did not die in vain.”

Censorship

Helping break through the parameters of acceptable discourse is just one challenge facing Palestinian writers. The other is having the freedom to talk about their everyday realities without being silenced.

The afterword to Rifqa quotes the late Ghassan Kanafani, the Palestinian author and official in the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, who was assassinated by Mossad, as well as his mother, who el-Kurd says faced repeated rejection for the content of her work.

No stranger when it comes to attempts to silence him and his sister, el-Kurd identifies three modes of censorship when it comes to Palestinians.

The first is censorship imposed by the Israeli state, the most obvious kind that affects Palestinians living under the occupation. Mohammed and Muna were arrested by Israeli forces in June 2021 after their campaign to stop settler appropriation in Sheikh Jarrah got global attention.

A less obvious and perhaps more insidious kind is the self-censorship that Palestinian writers often indulge in to cater to international audiences.

“I would lower my tone, pick my words more carefully because I would think in my mind that this audience in front of me may not be receptive to that discourse,” el-Kurd says, describing the mentality.

The third, according to el-Kurd, is a bias towards Zionism in some sections of the international media; restrictions, which seldom allows Palestinians to write their story as they see fit and works towards the service of the status quo.

“So you write an essay or an opinion piece for a certain mainstream American outlet and you’re now battling the editors to allow you to call things as they are.”

But while indignant, the young poet is equally unwilling to let any obstacle come in his way.

“Not every platform is a good platform,” he says.

“Thank God I am shameless about this and I’m not afraid to pick a fight about it."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].