Rabaa massacre: A bereaved father's eyewitness account

I suffer from heart problems, so I left the sit-in at Rabaa al-Adawiya Square at around dawn in need of rest on the morning of 14 August 2013. My apartment was just a five-minute drive away.

Exhausted, I went to sleep without switching off the television in the living room, set to a channel that was live broadcasting the sit-in.

At 7am, I was awoken by the sound of gunfire and cries for help emanating from the television. I rushed to see what was being broadcast and the scene was horrifying: a battlefield in the literal sense of the word, but a one-sided battle at that.

The coup’s forces had launched an attack to liquidate, under the pretence of breaking up the sit-in, the largest possible number of peaceful demonstrators, who were merely demanding that the constitution be upheld and the legitimately elected government reinstated. This is based on my eyewitness account.

Searching for my daughter

With my failing health and diminished strength, I wondered what could I possibly do if I returned to the square? What could I offer the demonstrators there? I thought, nothing at all.

Yet, how could I remain at home – as the frightening situation was unfolding – with my own daughter Habiba there? I found myself on the street looking for a taxi to take me to the nearest point to Rabaa Square. By then, it was closed off from a far distance by military forces who held protesters under siege.

I got off when it was no longer possible for the taxi to continue any farther. The tear gas was so thick that it was impossible to see, and I had nothing on me to protect myself from it.

I took a side road I had come to know from my repeat visits to the square during the sit-in, and reached the Rabaa mosque in a miserable state. Some youngsters pulled me towards them and gave me first aid.

I recovered some of my energy and leaned against the wall of a building in the centre of the garden near the mosque. Martyrs and the wounded were piling up in large numbers all around me, being carried on the shoulders of young men.

I grabbed my Quran and spent most of the day reciting verses and uttering supplications. Bullet casings rained down on me after hitting the wall under which I took cover. I then fell asleep.

Yes, I slept a deep sleep. I slept amid this hell for more than an hour. I did not feel any of the horrors that surrounded me from all sides, until I woke up suddenly to the ringing of my phone from inside my pocket. My wife was calling from the United Arab Emirates where my family was residing at the time.

How I heard the phone ringing over the sound of bullets and cries, I shall never know. It was almost 10pm at the time. “As-salamu Alaykum, Abu Habiba,” came the voice of my wife. “Habiba has become a martyr!”

“Praise be to God. We belong to God and to Him we shall return,” I responded. “Repeat with me Umm Habiba,” I said. “Praise be to God. We belong to God and to Him we shall return.” She repeated sombrely yet patiently.

With feelings of calm and serenity I had never known in all my life, I asked: “Where can I find Habiba?”

“Call her phone, and the person carrying it will tell you where she is,” answered my wife.

I obliged, and a young man answered, informing me that Habiba's body lay close to the Tiba Mall shopping centre. It was not possible to reach Tiba Mall through El-Nasr Road, the main street where the massacre was taking place. I took the parallel Anwar al-Mufti Street behind the Rabaa Mosque, only to arrive at a most shocking scene.

Street paved with bullet casings

The street was blanketed in bullet casings of various-sized calibres. A few protesters sheltering against walls shouted to me: "Go back, go back!" Others shouted: "Hurry up! Hurry up!" And another group shouted: "Take cover!" But I didn't go back, I didn't hurry, nor did I take cover.

Feeling numb to the threat of being shot and killed myself, I walked calmly towards where Habiba lay, treading over the bullet casings and blood-stained roads. On my way, a young man who was stuck behind an iron door, with a bullet lodged in its lock, called on me for help. I tried to help him with all my might, but to no avail. I told him that I needed to leave, and he understood.

I finally reached my daughter, whom I recognised immediately. She was the only girl - until that hour, in that place - among several martyred young men.

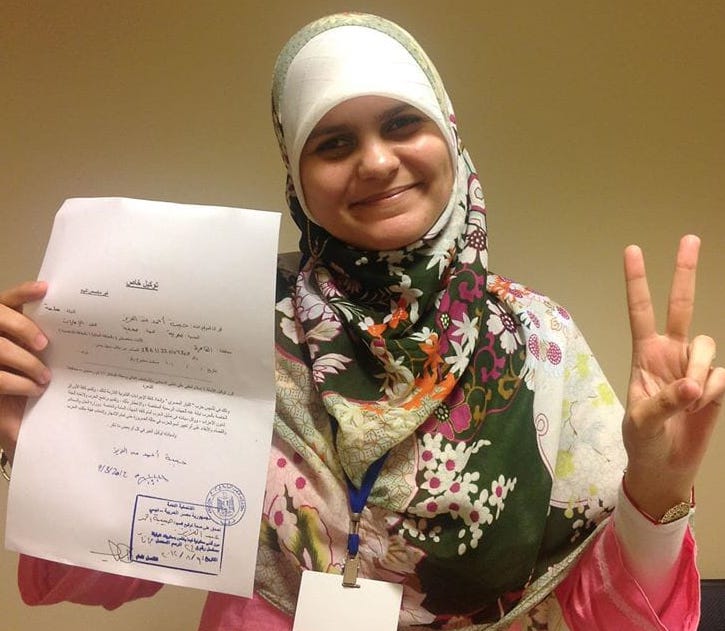

Survivors carefully wrapped her body in a plastic mat to cover her physical features, though her loose-fitting clothes had done so already. Habiba was prepared for this very scenario, as the messages she sent to her mother and her final Facebook posts indicated.

I knelt down and removed the mat from Habiba's face and planted a kiss on her forehead

I knelt down and removed the mat from Habiba's face and planted a kiss on her forehead. I felt overwhelmed with emotion and prayed for her. When I got up, a low-ranking special forces officer came towards me to offer his condolences, but I scolded him, turned away, and refused his condolences, so he retreated in silence.

There were a number of high-ranking special forces officers pacing back and forth aimlessly. They were terrified, as they were the main force responsible for carrying out the massacre. I asked the most senior officer among them, a major-general, to call for an ambulance to evacuate Habiba's body from the scene. He called time and again, but the ambulance never came. After six or seven hours of waiting, I decided to take matters into my own hands.

I searched around for a way to transport the body and found a small, rickety cart that seemed to belong to a street vendor. It was a wooden box with two handles on two wheels. Some young men placed Habiba’s body on the cart, with her upper body inside the box and her legs stretched over it.

I could not sway the men from accompanying me, and we proceeded to leave the place on foot and within range of the flying bullets.

My hope was to reach Abbas El-Akkad Street, as it was the closest safe point, after which it would be possible to move with relative ease to areas outside of the firing zone. Then, out of nowhere, the same junior officer I had scolded earlier appeared in his police truck and requested to help in an effort to protect us from the bullets.

The officer insisted that I ride next to him in the passenger's seat of the vehicle. Some young men climbed onto the exposed bed of the truck, grabbing the handles of the wooden cart, while others remained on foot, surrounding the truck to keep the body from falling. The officer drove at a similar pace to the young men.

Reporting the murder

When we reached Abbas El-Akkad Street, I met one of my neighbours, who immediately offered to help. We continued to transport Habiba’s body to the nearest hospital in Heliopolis, where bodies of the martyrs filled the hallways and rooms. I left the young men who kindly accompanied me to complete the hospital procedures, and then went to the nearest police station to file a report of the murder.

The policeman on duty began writing the report, and when he reached the inevitable question: Who do you accuse of killing your daughter? I said: Counsellor Adly Mansour [appointed as interim president]; Dr Hazem al-Beblawy [the first prime minister after the coup against the elected president]; Minister of Defence, General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi [the coup leader who ordered the murder], and Interior Minister Major-General Mohamed Ibrahim [who presided over the Special Forces who carried out the murder], among others.

The policeman shivered and hesitated to write down the names, so I yelled at him and almost slapped him in the face

The policeman shivered and hesitated to write down the names, so I yelled at him and almost slapped him in the face. He then wrote down the names with a trembling hand. At the very least, the murder and some its perpetrators’ names were documented in an official affidavit.

When I returned to the hospital, the men who accompanied me had been waiting so that we could rent a vehicle to transport the dead. As we passed the hospital’s outer door, a number of family members stopped us and requested we take the bodies of their loved ones to the Zeinhom morgue.

I spent the night there sprawled across the dirt, next to rows of martyrs that extended as far as the eye could see, in all the streets surrounding the morgue. People continuously placed blocks of ice on the martyrs’ bodies to preserve them in the blazing August heat.

The next morning was Habiba's turn for an autopsy. In his report, the forensic doctor determined the cause of death as "a gunshot wound to the chest, penetrating the heart, smashing the ribcage, and exiting from the lower back”.

The distance between the inner and outer doors of the morgue was no more than 20 metres, but it took us two hours to cross to the exit. All the while, Habiba was being carried on the shoulders of some young men who insisted on relieving me, as they awaited doctors' findings on their slain loved ones. Had it not been for them, I believe I would have either perished from exhaustion and grief, or been stuck in the morgue for several more days.

A hearse then transported me and Habiba to the mosque adjacent to my apartment in Nasr City. One of Habiba's friends volunteered to wash her body before we headed to Kafr Hamam, a village in the Monufia Governorate and my family's home town.

We arrived at the home of my relatives, who were ready to receive Habiba. My family had also arrived from UAE and we all gathered around the coffin to bid her farewell.

Habiba appeared to be sleeping, not dead. Her body was tender, as if she were alive, blood dripping from her nose, and she had a pleasant scent.

The villagers walked into the procession, ululating in honour of Habiba and chanting condemnations of the coup - in a manner that my spirited daughter would have approved. We then performed the funeral prayer in the mosque of the graveyard and laid her to rest.

Exposing the lies

Burying our loved ones does not mean burying the truth. Nine years after the massacre, there are several matters I would still like to highlight.

First, while investigators have placed the number of those killed at Rabaa from 817 to more than 1,000, I estimated the number of martyrs to be much higher. It is my contention that the largest number of protesters were bulldozed, and their whereabouts remain unknown.

It is my contention that the largest number of protesters were bulldozed, and their whereabouts remain unknown

Second, the Rabaa sit-in was unarmed, except for some batons that were necessary to secure the sit-in square from any possible attack by thugs and attacks similar to the "battle of the camel" incident that took place in Tahrir Square in February 2011.

The peaceful protesters were not equipped with any means to repel an armed attack by regular military forces, evidenced by the enormous death toll. This is my conviction, and only God knows the full scale of what took place.

It is without a doubt that the coup’s enforcers filmed the massacre, and had they possessed a single video clip proving that the protesters initiated fire against the attacking forces, they would have shown it repeatedly and made it into a “historical” record of the Muslim Brotherhood’s “terrorism”, which was (is and will continue to be) an unfounded despicable claim to justify their persecution of the organisation for more than 70 years.

Third, the sit-in was surrounded by several military and security offices. Given that thousands of protesters marched down the streets of these buildings, had they had ulterior motives, they could have easily taken over these headquarters with minimal loss of life.

I participated in a number of these marches and did not once see a protester throwing even a brick at any of these buildings or at a conscript guarding them.

Fourth, there shall be no recognition of the coup’s authority, no dialogue with the murderers, and no forgiveness for those criminals who committed this heinous crime, premeditatedly and determinedly, with the sole aim of shocking and intimidating so as to demonstrate their complete control over the country.

As such, they deserve to be in courts of law, not at tables of dialogue or negotiation.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].