Algeria is buying time with the gas bonanza, but disaster looms

French Prime Minister Elisabeth Borne and more than a dozen ministers landed in Algiers earlier this month to strengthen ties with the major gas exporter. Just six weeks after French President Emmanuel Macron visited Algeria, the two countries signed 11 agreements to enhance cooperation in a variety of sectors.

Amid a serious energy crisis caused by Russia’s war on Ukraine, which has reduced supplies to Europe and increased energy prices, France is taking significant steps towards repairing its strained ties with Algeria - and it is not the only country courting the North African state. Several European governments are seeking alternatives, and European Council President Charles Michel recently touted Algeria as a “reliable” gas supplier.

The government no longer has the financial resources necessary to restructure Algeria's economy

On the southern side of the Mediterranean, the increase in oil and gas prices - with gas prices now 10 times higher than they were a decade ago - has prompted Algerian authorities to abandon austerity policies, cancelling tax increases and subsidy cuts that had been implemented to help deal with the country’s pre-pandemic fiscal challenges.

The war in Ukraine and the accompanying extra gas revenues will buy time for Algeria’s decision-makers, but it will not allow them to avert economic catastrophe. Yet again, the Algerian regime has been temporarily saved by the bell: it will continue to avoid enacting genuine change and reform, using rent revenues to sustain patronage networks and buy social peace when unrest erupts.

This is the subject of the fourth chapter of my latest book, Understanding the Persistence of Competitive Authoritarianism in Algeria, which explains the five pillars that have been sustaining the Algerian regime since the country’s independence in 1962. Without these five pillars, the regime would not have been able to weather the crises it faced in 1988, 1992, 2001, 2011 and 2019; rather, it would have collapsed long ago.

Five pillars

The army, Algeria’s true source of power, is the first pillar. The second is the co-option of the opposition; the third is the fragmentation of civil society; the fourth is rent distribution, corruption and patronage; and the fifth is repression.

Oil-extracted revenues have long been the regime’s preferred method for purchasing social peace and citizens’ political allegiance. The regime uses hydrocarbon money to distort the political process, supporting pro-regime incumbents during elections and enabling them to improve economic opportunities for the regime’s clients and allies.

The regime’s corruption has a political dimension, as a portion of illicit profits are allocated through patronage networks. In my book, I examine how the regime accomplishes all of this, including how it sometimes compensates individuals it has excluded from the system in order to keep them from speaking out.

The country’s leaders will continue to keep their tight grip on power through a carefully calibrated use of the country’s economic resources to bind the coastal elites of Algerian society to the state.

The allocation of a portion of oil and gas rents to the elites has resulted from the selective liberalisation of the economy. For decades, these elites have dominated private enterprise, and they periodically establish or fund business-friendly political parties to increase their influence in parliament.

If properly compensated, these elites function as an effective mediator between the regime and the masses, especially by supplying employment prospects. To this end, the regime has transformed certain economic sectors, such as defence and hydrocarbons, into sources of political patronage for the elites, who then distribute favours and jobs to the working classes.

Financial cushion

But as dissatisfaction has grown among working-class Algerians, the regime has redirected its economic generosity to benefit these individuals directly. This occurred during the earliest stages of the 2011 Arab Spring, which began in neighbouring Tunisia and threatened to consume Algeria and the rest of the region.

The regime in Algiers benefited from high oil prices during the early 2000s, so much so that Algeria ranked 13th worldwide in terms of foreign exchange reserves in 2013, with $194bn. This comfortable financial cushion enabled the regime to use economic resources to lead potentially discontented parts of society into complacency, and to purchase social peace.

The government invested astronomical sums into public-sector wages, infrastructure, social housing and job development. To reduce unemployment among young people aged 15 to 34, comprising more than a third of the population, the government established the National Youth Employment Support Agency. Between 2011 and 2019, it granted funds worth at least $20bn, most of which were distributed as bank loans, allowing unemployed people to launch businesses and achieve a degree of economic security.

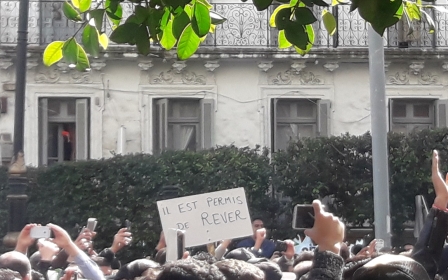

The strategy was successful, notwithstanding the mass protests in 2019 that toppled President Abdelaziz Bouteflika. The regime and its extensions - political leaders, senior military officials and business tycoons - contained the opposition, impeded mass mobilisation, and ensured the compliance, and even loyalty, of the majority of the population. The regimes of Tunisia, Egypt and Libya were toppled successively. But Algeria’s remained standing, and a decade later, it is still standing.

Future outlook

Today, the regime continues to follow the same method of rent distribution to calm social dissent. This past February, as the Ukraine war erupted, bringing the prospect of additional gas revenues, authorities announced a new unemployment stipend for first-time job seekers that would benefit 1.5 million people.

Once again, key decision-makers - the army, the National Liberation Front, the Democratic National Rally and the country’s coastal elites - have skilfully managed the regime’s continuity. Through prudent and opportune political openings and economic interventions, they can avoid systemic restructuring.

Going forward, Algerian authorities are likely to encounter additional societal unrest

Increased income from oil and gas exports will result in a major reduction in the need for external financing and a short-term stabilisation of domestic financing needs. In the meantime, the economic recovery in non-energy sectors has stalled, while inflationary pressures have risen. The economic outlook is a moderate recovery over the next few years.

However, the continuing slowdown in economic development outside the energy sector will surely lead to an increase in already-high unemployment and a decline in earnings. As the social and economic situation worsens, the significance of social issues will only increase. The government no longer has the financial resources necessary to restructure Algeria’s economy, diversify its productive sectors and increase its competitiveness.

In fact, despite ongoing discussions around diversifying the economy to lessen reliance on hydrocarbons, curb corruption and improve the business environment, the government has done almost nothing to bring about real change. Going forward, Algerian authorities are likely to encounter additional societal unrest.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].