Murder in Cairo: How the West should respond

Ten days after he vanished from the streets of Cairo, Giulio Regeni’s battered body was found in a ditch not far from the Pyramids in Giza on 3 February. The Italian student, who was studying for a doctorate from Cambridge University, was naked from the waist down. According to preliminary coronary reports from Italy and Egypt, his finger and toenails had been pulled out, there were cigarette burns around his eyes and feet and numerous cuts on his face. His spine had been broken.

There is little doubt that Giuilio Regeni died a protracted, agonising death; little doubt, that is, unless you are an Egyptian policeman. The head of the Giza Investigations Unit, Khaled Shalaby, initially claimed that the Italian had died in a traffic accident.

Officials later changed their mind, insisting that Regeni had fallen foul of criminals, and appeared scandalised by accusations in the Italian press that the real perpetrators were probably the Egyptian security forces themselves. “There are many rumours repeated on the pages of newspapers insinuating the security forces might be behind this accident,” spluttered Magdi Abdel Ghaffar, the country’s interior minister. “This is unacceptable. This is not our policy.”

Sadly, it is precisely because torture, abduction and extra-judicial killings are the policy of the Egyptian security forces - particularly since Ghaffar took office last March - that the regime is prime suspect in the murder.

Since Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi, the Egyptian president, seized power in July 2013, Egypt has embarked on a programme of repression unparalleled in the country’s modern history. Tens of thousands are being held prisoner for political reasons; hundreds more are disappearing into secretive detention centres, where even the pretence of due process has been abandoned. Some of those abducted are believed to have been killed. Dissent has been crushed; so suffocating is Sisi’s Egypt that it is now a crime for more than 10 people to gather without getting prior police approval. And let us not forget that the regime presided over the killing of nearly 1,000 protesters in Cairo’s Rabaa Square after Mohamed Morsi was ousted.

In the face of this appalling catalogue of state crimes, the West has largely stayed silent. The belated discovery of principle that seeped into Middle East policymaking as the crowds swelled in Tahrir Square has ebbed as Arab Spring turned to winter.

Spooked by the Muslim Brotherhood’s time in government, the West sees President Sisi as a return to a Mubarak-style model of authoritarian stability that is of comforting familiarity to Western foreign ministries. Compared with most other Arab Spring participants, Egypt does indeed look stable. Moreover, Sisi is seen as an ally in the struggle against the growing Islamist threat in Sinai and neighbouring Libya.

So perhaps it should be of little surprise that the response in European capitals to Regeni’s murder has been muted. Outrage has largely been limited to Italy, which ironically had been one of President Sisi’s biggest Western cheerleaders. The British government has been conspicuously silent about the affair, giving the impression that David Cameron - who welcomed Sisi to London last year - does not think that the likely murder by a foreign regime of a student at one of Britain’s foremost universities is a big deal.

Yet coddling Sisi on the grounds that he is a guardian of stability is contorted casuistry - as far-fetched as saying that Regeni died in a car accident. In the past 12 months, Egypt has lost control of much of Sinai to Islamist terrorists, seen terrorism elsewhere flourish and experienced the destruction by bomb of a Russian airliner. Then there was September’s debacle in the western desert; a country whose police kill tourists after mistaking them for terrorists meets few criteria for stability.

In fact, the regime’s repression only makes Egypt more unstable. Previous Egyptian presidents have locked up thousands of Muslim Brotherhood members, only to make the movement stronger. State brutality also bolstered more radical groups which, unlike the Muslim Brotherhood, did not renounce violence. It is no coincidence that Ayman al-Zawahiri, the al-Qaeda leader, was tortured in an Egyptian prison cell.

It therefore makes little sense for the West to indulge a man whose policies could potentially serve as a recruiting tool for Islamic State. Regeni’s murder represents a tragic opportunity to change course, and the European Union should take the lead.

Some European officials might feel reluctant to be too firm given that we cannot say with certainty who killed Regeni. Yet the circumstantial evidence is pretty compelling. He disappeared en route to a meeting with a friend near Tahrir Square on 25 January, the fifth anniversary of the 2011 uprising. Thousands of jittery security forces were on the streets looking for trouble, making it unlikely that criminals were responsible. The police have a motive too; although he was probably picked up at random, Regeni could easily have been mistaken for a subversive. He was a student researching labour movements – all too redolent of the April 6th movement, a student-trade union coalition that was a driving force behind the 2011 uprising – who was also writing as a journalist under a pseudonym.

We are unlikely to know what truly happened. Although Sisi has bowed to pressure by allowing Italian police to travel to Cairo, they will be forced to work alongside the Egyptian security forces, the main suspects in the killing.

So what can be done? The investigation should represent the first point of pressure. Any form of obstruction from the Egyptian police should be met with a tangible and public response from the EU.

But Europeans should not shy away from tougher action now. In 2012, the US Congress passed the Magnitsky Act imposing sanctions on Russian officials suspected of human rights abuses and corruption. No single action by the West has angered the Russians more. Europe should adapt this measure to Egypt, imposing sanctions against politicians, military and security officials at the heart of the regime. Interior Minister Ghaffar would be a good place to start.

Tough, concerted European action could convince Washington to follow suit, perhaps by linking the $1.3 billion it gives in military aid each year to a genuine improvement in human rights.

Egypt is more vulnerable to Western pressure than ever before. Economically Egypt is in a parlous state, dependent on Gulf largesse that could soon run out. Regionally, the country is no longer the power it once was. It has played almost no role in US-led military action in Syria and Iraq. Its once hugely symbolic peace treaty with Israel counts for little with the peace process seemingly moribund – indeed Mr Sisi realises this, which is why he is desperately trying to partner with France to resurrect Israeli-Arab talks and thus make Egypt indispensable again.

The time for timidity is gone. By standing up for Regeni, the EU would stand up for every Egyptian murdered, tortured or wrongfully imprisoned by the state. Failing to do so will embolden the repressive organs of the state, betray Arab citizens everywhere who dream of a democratic future and convince many in the Middle East that the West’s moral values are all so much hypocrisy.

- Adrian Blomfield was Jerusalem Bureau Chief and Middle East Correspondent for the Daily Telegraph from 2009 to 2012.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

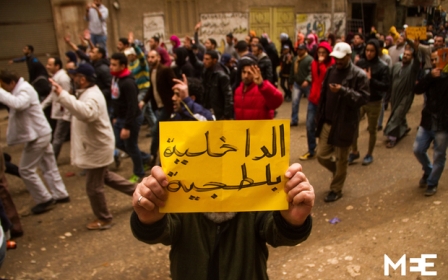

Photo: Activists and Italian nationals living in Egypt take part in a rally in memory of Italian student Giulio Regeni on 6 February, 2016, outside of the Italian embassy in Cairo (AFP).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].