The Palestinian Museum: A safe place for unsafe ideas

WEST BANK, Palestine - Atop the hills of Birzeit, a university town about 20 miles north of Jerusalem, a new, modern structure presides over the green, terraced landscape. Men in hard hats mill around the sandstone and glass facade in the early March sun, but soon they will be replaced by the building’s new keepers: the staff of the Palestinian Museum.

When it opens to the public in mid-May, the Palestinian Museum will be the first public museum of its kind in Palestine, and one of the most unique museums in the world. Conceived, funded, and realised with the Israeli occupation constantly looming in the background, the museum aims, as its motto states, to provide ''a safe place for unsafe ideas.''

A safe place for unsafe ideas

Compiling the fragmented history of Palestine and its people, both at home and in the wider diaspora, is no short order. The museum had to take an innovative approach in its research and exhibition programmes, which are specifically tailored to represent an Arab history so long marginalised and disappeared by the ongoing Israeli occupation of Palestine.

The initial idea for the museum was conceived 18 years ago by the Welfare Association, an international non-governmental organisation dedicated to the development and conservation of Palestinian identity and cultural patrimony. Omar al-Qattan, the chair of the museum task force, has been instrumental in realising the project, and remembers the initial discussions of how best to present the cultural history of Palestine.

“There was no agreement at first because the owners of the museum are a membership organisation with a lot of different views,” Qattan explained during a recent trip to meet with staff in Ramallah and Birzeit. “There were generational differences, and also different understandings of what museums were. One camp was led by the late profesor Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, from the Nakba generation – he proposed the project as a memorial museum. A group of us who were younger said hang on – yes that’s fine, but we also want something that speaks about contemporary Palestine and also to help us look at what the future might look like.”

Qattan’s ambition to create a thematic museum, with a research-led exhibition programme and a reach beyond Palestine, was put on hold when the Second Intifada broke out in 2000. Ideas and plans flew back and forth between members for the next decade, and in 2010, an architectural competition was held to design the new building. Fundraising began in 2011, and the construction of Phase 1 of the museum began in 2013.

“The concept that I proposed is still there – the core concept, the idea of a mothership [central hub] with satellites [outposts] to reflect the Palestinian dispersal and the fact that communication is so difficult,” Qattan said. “The idea is that we will build our collection, whether digital or physical, led by the research. It will be within the needs of our programmes.”

A mothership and its satellites

Though the building, which Qattan and his team refer to as the ''mothership,'' will open in May, its exhibition programme will not get going until autumn.

As with any project of this size, there have been teething problems: delays and funding pressure, exacerbated by the current political conflict and its restrictions. Creative director Jack Persekian left the museum at the end of 2015, and the planned inaugural exhibition, an exploration of ordinary Palestinian’s most valued possessions entitled Never Part, was put on hold.

But a key part of the museum’s plan is to reach Palestinian communities abroad. Rachel Dedman, an independent curator based in Beirut, was invited to head up the first of its satellite exhibitions, scheduled to open in Beirut at the same time as the opening of the Birzeit space in May. Instead, she has found herself at the helm of what’s become the museum’s inaugural exhibition At The Seams - an in-depth, multimedia history of Palestinian embroidery - even if it is happening some 150 miles away from the museum itself.

“A physical space is really crucial because it goes back to what a museum can actually do, which is operate as resistance against existential threats, and the physicality of the space is really important,” Dedman said from Beirut via Skype, referring to what she sees as the museum’s dematerialised practice. “At the same time, the satellite idea is really fascinating because it responds to a global need for museums to respond to and reflect the global nature of their audiences. And especially with Palestinians, who for so long have been displaced, forced out, marginalised, denied voice, and have been living all over the world for a long time now, the satellite concept allows for these ideas to be enhanced and stretched.”

Dedman explained that her desire to animate the cultural artefacts included in At the Seams gelled with the museum’s commitment to long-form, in-depth research. The exhibition, which opens on 25 May at Dar el-Nimer, draws from private embroidery collections, image and text archives, and original interviews, as well as collaborations with contemporary Palestinian designers and a commissioned film based on Dedman’s fieldwork.

“My research unfolded from the belief that material culture - as things that are made to be worn on the body and are made by people - is inherently political,” Dedman said. “They can tell us something of Palestinian history including Palestinian history in Lebanon that will open up really fruitful conversations and discussions today. For me, this really extends the remit of the museum itself – to start a conversation, to be a safe space for unsafe ideas and to engage its broad audiences from wherever they may be.”

A Palestinian family album

While the exhibition programme at the mothership in Birzeit remains in flux until a new creative director is appointed, the team on the ground has also been busy focusing on the key virtual elements of the Museum’s mission.

In an effort to reach Palestinians in the diaspora, as well as an international audience who may not otherwise engage with everyday Palestinian stories, the heart of the museum’s web-based platform is found in its Family Album project.

Alongside an interactive historical timeline, the Family Album archive showcases everyday family photographs alongside detailed interviews with their owners, and will be available in an online database sometime this summer.

“The Family Album started off with the concept that family photos are something we all hold onto and hold dear to,” Dalia Othman, the manager of the museum’s audio-video archive said. “It’s a great window to see family traditions, customs, culture, significant moments in history. It’s a great way to find a way through Palestinian history, through those photos.”

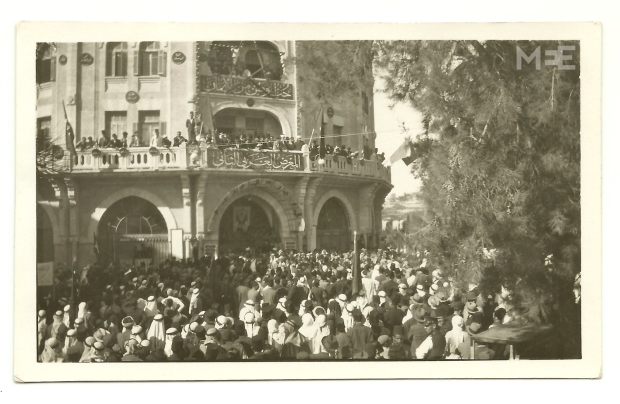

At the end of 2014, the archive team began spreading the word through family and friends that they were looking for photographs – any photographs. Initially, they set up a tent for two days in al-Manara Square at the centre of Ramallah to explain to anyone passing by that their old family photographs could help illustrate the larger history of Palestine. Word spread, and to date, the archive has amassed approximately 10,000 digitally-scanned photographs.

In line with the high standards of the museum, which has been recognised by the International Council of Museums, the archivists went around Palestine with digitisation contracts and spent time recording the minute details of every photograph taken. After two weeks in museum custody, the photographs were returned to their owners with a digital CD of the scans, as well as instructions on how to properly preserve these valuable documents.

“Our goal is to connect Palestinians with each other,” Othman said. “This is an analytical view of Palestinian history, and because it’s digital, because it’s online, because it’s not going to be physical, people from across the world can access that content. It’s creating that bridge with the diaspora to connect and reconnect with these roots.”

In the face of many internal and external challenges, Qattan is proud of the museum’s innovative programmes and platforms. But he is also acutely aware of the varied problems that may lie ahead after the doors open in May. Despite their attention to security, some things will remain out of the museum’s control.

“I think that this is probably the first museum that was built under military occupation, so it’s quite amazing to be here, to be this far,” Qattan said with a laugh. “But that also comes with its own problems, because we don’t have freedom of movement, nor does our local audience. We are very vulnerable to the violence of the settlers, and the Israeli army, and people are obviously very wary of supporting or funding a project that is fragile. But it’s a risk one has to take.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].