Is Turkey heading for a cold war with the EU over offshore Cyprus gas?

Just as Turkey braces itself for possible sanctions from the United States over its purchase of S-400 anti-aircraft missiles from Russia, news has broken that it is facing another set of sanctions, on an entirely different, but at least equally intractable issue, from the European Union.

Though they have so far received relatively little attention in Turkey or the rest of the world, the scene is now set for a deepening political and diplomatic confrontation which could be very hard to reverse. If so, these EU sanctions mark a new stage in the unfolding process of Turkey estrangement from the West.

News of the sanctions came on Monday when the European Council (the meeting of EU heads of government) announced that it was imposing sanctions against Turkey for drilling in the seabed off Cyprus which it regards as illegal.

New sanctions

The sanctions are not about Turkey’s long-stalled application for EU membership, which is now so dormant that for most purposes it can be regarded as dead, largely due to the Cyprus dispute.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Now a country which is in theory still a membership candidate is faced with sanctions which strike at routine working relations between Turkey and the EU. Negotiations on the Comprehensive Air Transport Agreement are suspended.

The financial sanctions have not been spelt out in detail but at a time when the Turkish economy is under serious strain, they clearly add to the country’s difficulties

The regular Turkey-EU Association Council and further meetings of the EU-Turkey high-level dialogues are called off “for the time being".

Pre-accession assistance to Turkey for 2020, likely to be worth around €800m ($900m) over a year, will be reviewed.

The European Investment Bank will review its lending activities in Turkey, notably with regard to sovereign-backed lending. The two financial sanctions have not been spelt out in detail but at a time when the Turkish economy is under serious strain, they clearly add to the country’s difficulties.

A predictable outcome

The confrontation is a fairly predictable outcome of Turkey's move to drill in the sea bed around Cyprus. During the last three years Turkey has purchased and fitted out two prospecting vessels, the Fatih and the Yavuz, and sent them into Mediterranean waters.

Earlier this month, the Fatih was 37 nautical miles west of Cyprus in an area of open sea which both Turkey and Cyprus claim as their Exclusive Economic Zone, while the Yavuz was drilling northeast of the islands, in waters which are claimed by the Greek Cypriots but have been controlled since 1975 by the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

By moving the vessels into these disputed waters, Turkey has defied not just the Greek Cypriots but also the EU and the United States as well

By moving the vessels into these disputed waters, and particularly those west of the island, Turkey has defied not just the Greek Cypriots – whose government it does not recognise and which is the country chiefly responsible for blocking Turkish EU membership - but the EU and the United States as well.

Both the EU and the US issued warnings, something that would have been unthinkable a few decades back when the West tried to maintain its neutrality in the disputes between Turks and Greeks, and regarded Turkey – with a population eight times that of Greece with a key geostrategic location - as an indispensable partner.

The gas discoveries

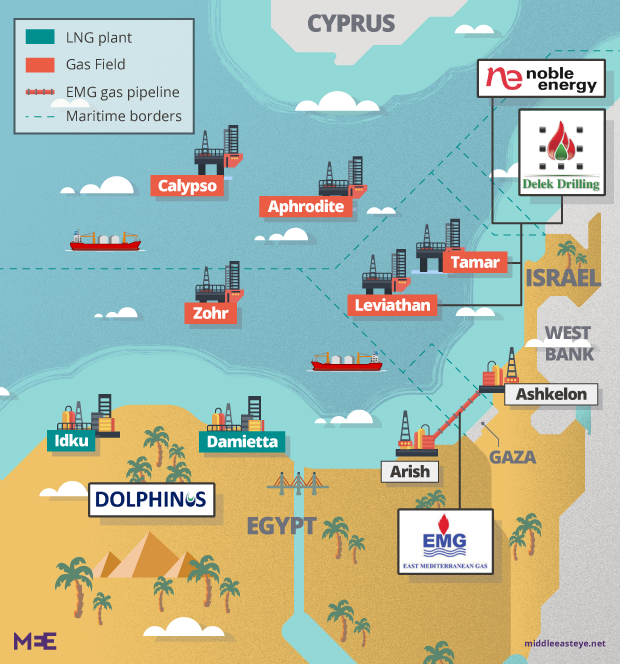

Over the last decade there has been a succession of large natural gas discoveries in the eastern Mediterranean, notably the Zohr field off Egypt and Leviathan and Tamar fields off Israel, and the Aphrodite gas field southeast of Cyprus. It looks as if there could be total reserves around 125 trillion cubic feet in the area.

Turkey, which has a 1,500-km Mediterranean coast, only exceeded by that of Greece with its islands, has been disputing seabed rights issues with Greece in the Aegean since the 1970s without a compromise being reached.

There is no sign Turkey will back down. Instead even the left of centre opposition has rallied to support President Erdogan’s line

The International Law of the Sea – which Turkey does not recognise –gives islands priority over the seabeds adjacent to their mainlands, a situation which seems in Turkish eyes unjust. The Greek Cypriots, with a coastline of 648km, get the lion’s share of seabed rights, even though much of their seabed is not actually controlled by them.

Since the Turks invaded the island in 1974, invoking treaty rights to protect their minority there, the northwestern and northeastern coastline of the island has been controlled by the Turkish Cypriot state, an entity recognised by Turkey but no one else.

Last February, Exxon Mobil announced the discovery of reserves between 5 and 8 trillion cubic feet of gas in Zone 10, the biggest gas discovery anywhere in the world in 2019. This came despite earlier attempts at a blockade of prospecting operations by the Turkish navy. This week Fatih announced that it, too, had made a substantial discovery of gas deposits in the disputed zone.

Last January, several Mediterranean countries set up the East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), which will consider issues like the construction of pipelines, initially perhaps to a refinery in Egypt but later to Greece and European markets.

Three countries in the Eastern Mediterranean – Turkey, Lebanon and Syria - were not invited to take part in the EMGF, and, even if they are admitted some day, may find themselves having to fit in with arrangements not designed with their interests in mind.

No backing down

What seems to be happening instead is that the United States and Israel are forging an energy alliance to build an Eastern Mediterranean pipeline (EastMed) with Greece and the Greek Cypriots. A visit to Israel by Mike Pompeo, the US secretary of state, to discuss this alliance, took place on 21 March in Jerusalem.

The implications for Turkey are obvious – and completely unacceptable. A trilateral partnership of Greece, Cyprus and Israel has been declared, and the US will, according to legislation going through Congress, support it in both energy and security matters.

The stage is being set for a strategic confrontation in the Eastern Mediterranean between the US and two very small countries against the largest and strongest nation of the region, which until now saw the Eastern Mediterranean as its area of influence.

With two votes inside the European Union and Washington behind them, the Greeks and Greek Cypriots have had - surprisingly - little difficulty in getting the EU behind them too.

This is happening at the price of releasing nationalist antipathies and ancient grievances which may prove difficult to quell. For two months, the Nicosia government has been warning that it will prosecute those on board the Fatih, who are believed to include Croatian and British citizens, using the European Arrest Warrant.

The confrontation being created now could easily become permanent and impossible to reverse. Turkey’s reaction to the news from the EU has been predictable.

There is no sign it will back down. Instead, even the left of centre opposition has rallied to support President Erdogan’s line. Turkey is not withdrawing the Fatih. It says it will send out two more prospecting vessels and it will protect them if necessary with its navy.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.