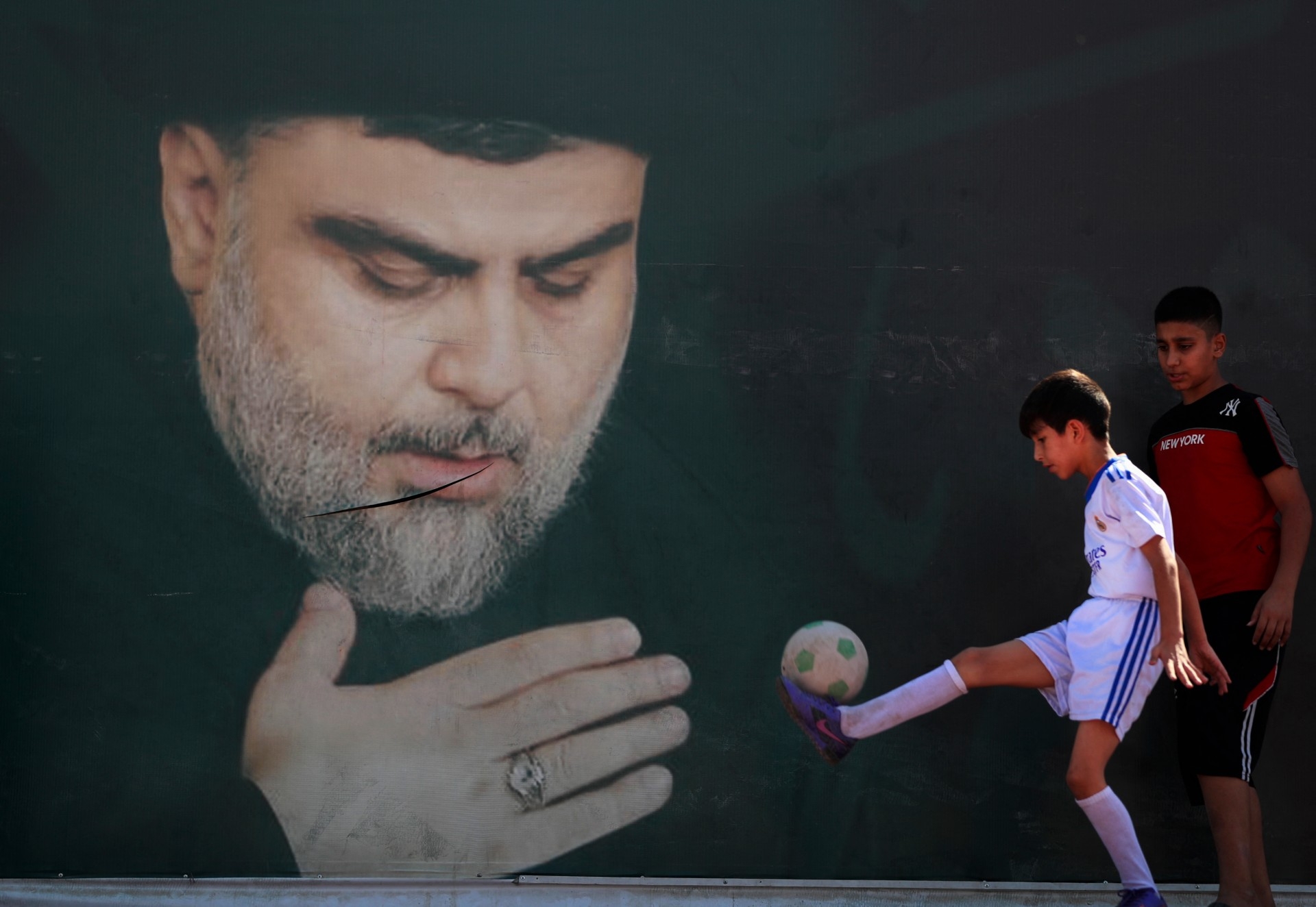

At a lunch in Najaf, Muqtada al-Sadr tries to divide and conquer

Two days ago, four men gathered for lunch in Najaf at the house of Muqtada al-Sadr's father.

The influential Shia cleric, riding high after his parliamentary election victory was confirmed this week, had invited Hadi al-Amiri, head of the Fatah bloc, Qais al-Khazali, commander of the powerful Shia armed faction Asaib Ahl al-Haq, and Faleh al-Fayyadh, head of the Popular Mobilisation Authority paramilitary umbrella group.

They were there for negotiations, and to "discuss their visions about forming the next government," a source close to one of the four leaders told Middle East Eye.

It was here that Sadr revealed his ideas for Iraq's political future: a majority government, led by himself, that leaves former prime minister Nouri al-Maliki and a number of Shia political forces out in the cold.

According to two Shia political leaders familiar with the meeting in the holy southern city, Sadr gave detailed plans to his guests. However, the "closed" lunch, which lasted several hours, "ended without leading to any real progress," one of the leaders said.

There is only a limited amount of time before Iraq's new parliament gathers to elect the country's next leaders.

On 27 December, the supreme court finally ratified the results of October's parliamentary election. Sadr emerged as victor, with his list winning 74 seats. Outgoing parliament speaker Mohammed Halbousi's Taqadum came second with 42, and Maliki's State of Law third, securing 35.

Fatah, the political wing of the Iranian-backed armed groups, was one of the biggest losers in the elections: the faction's Alliance candidates won just 17 seats, less than half of its return in the previous election.

Now comes the parliamentary session to elect the president, prime minister and speaker, which has been arranged for 9 January. Iraq's political system mandates a national and sectarian balance in these top positions, which means they must be taken by a Kurd, a Shia and a Sunni, respectively. All must be assigned at the same time.

'The Shia forces fear Sadr forming a government, and they also fear him going to the opposition'

- Senior Shia leader close to Iran

Sadr hoped the lunch in Najaf would speed up government-formation negotiations ahead of the 9 January meeting of parliament.

"Sadr is still insisting on forming a political majority government that includes a number of the Shia forces that won the elections, but not all of them," one of the leaders who attended the Najaf meeting told MEE.

"He says that the interest of Iraqis requires pushing one of the major Shia forces to the opposition, while another Shia force forms the government and bears full responsibility for its performance and the performance of its prime minister and ministers."

Yet the leader was not convinced of Sadr's vision.

"We cannot be satisfied with the dismantling of the Shia blocs while the Kurdish and Sunni blocs join together in the Sadr formation. This will lead to the weakening and dispersal of the Shia forces."

What Sadr really wants

Since the first election in the post-Saddam Hussein era, in 2005, Iraq's political forces have shared power by divvying up ministries and other state organs between them in proportion to the number of parliamentary seats they have won.

This power-sharing system has meant the almost complete absence of a parliamentary opposition that monitors government performance and seeks to corrects its tracks. Inevitably, that has contributed to the longstanding financial and administrative corruption that plagues Iraq.

It has not produced stability, either. Political forces jostle, compete and undermine each other in a struggle for ever-greater legitimate and illegitimate gains. Ahead of the October election, various incidents affected sectors under Sadr's watch - health and electricity - which prompted the cleric to accuse his rivals of trying to weaken him.

Around 150 people were killed in two hospital fires in Baghdad and Nasiriyah in April and July, incidents in which corruption and negligence seemed to play a major role. Similarly, dozens of power transmission towers were sabotaged in the central and southern governorates in the same period, places also run by Sadr's allies.

Sadr, crying foul, pledged at the time to form a majority government if his list was elected as the largest bloc. Yet Sadr and his preferred partners have not quite won enough seats to form an outright majority, forcing wider negotiations to pick the president, prime minister and speaker.

To confront Sadr, the losing Shia forces, led by the armed factions linked to Iran, revived the "coordinating framework of Shia forces," an old political formation. But Sadr's representatives boycotted it before the elections. Maliki, Sadr's arch-enemy, then assumed the presidency of the "coordinating framework," as he has the largest number of seats among the framework forces. Without Sadr, the grouping combines around 60 seats.

Now we have Sadr, still bent on forming a majority government, versus his Shia rivals, who are determined to keep the power-sharing system.

One tactic used by Sadr, according to a Shia political leader, is offering to hand over responsibilities for forming the government and go into opposition himself.

"In short, Sadr is seeking to dismantle the coordination framework, while they are seeking to force him to return to their embrace. The Shia forces fear Sadr forming a government, and they also fear him going to the opposition," a senior Shia leader close to Iran told MEE.

"Sadr going to the opposition means that the next government will never be stable, and that it may fall after months or weeks. As for his complete control of the government and parliament, it will mean that he will pursue them one by one.

"Sadr will not forgive them for what they did to him before the elections, and he will not forget his old rivalry with Maliki and Khazali."

Expected scenarios

Sadr knows his opponents well. He is familiar with the strengths of the "coordinating framework," but more importantly its weaknesses.

Maliki, Amiri and Khazali all want to be seen as the top leader of Iraq's Shia forces associated with Iran. This competitiveness has gifted Sadr an opportunity to try to prise Amiri, Khazali and Fayyad away from their allies.

Khazali, who aspires to lead the armed Shia factions and the Fatah bloc, has real problems with Amiri, the Fatah leader accused of overseeing the chastening election loss.

There are also disputes between Khazali's Asaib Ahl al-Haq and other armed factions, led by Kataeb Hezbollah, over leadership, influence and revenues.

'The strange thing is that Iran and America have not yet intervened, meaning that the game is still purely local, and Najaf has not yet said its word'

- Prominent Shia leader

Sadr could provide Khazali cover and protection amid these disputes, and the Asaib leader is reportedly interested in what the cleric is offering.

On the other hand, Fayyadh has become the weakest link of all the Shia forces linked to Iran since the January 2020 killing of Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the godfather of the armed factions who was Fayyadh's greatest supporter. With no real support on the ground, he needs a new protector to assure his place as head of the Popular Mobilisation Authority, a position coveted by many.

As for Amiri, who leads the veteran Badr Organisation, it is known that he is the least inclined to engage in political conflicts, and he has a reputation for stability and pragmatism.

Despite Amiri's great disputes with the commanders of the armed factions about some of their policy positions on Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi and Sadr in recent months, he has never sought to be a tool in deepening these disputes and has always played the role of mediator between all the conflicting parties.

It is expected, therefore, that he will eventually join Sadr as a "calming factor" between the cleric and his Shia opponents.

Few options

After the meeting with Sadr on 29 December, Amiri returned alone to Baghdad to meet with the leaders of the coordination framework in Maliki's house. Khazali and Fayyadh did not attend that meeting.

"Currently, there are not many options for everyone. Either Sadr abandons his project and allies with the forces of the coordination framework to form a power-sharing government, or he withstands pressure and proceeds with his project," a prominent Shia leader close to Iran told MEE.

"Sadr's success would mean the disintegration of the coordination framework, and since this formation is based on temporary tactical alignments rather than strategic political alliances, its disintegration is likely."

Unusually for Iraq, three powerful influences - Washington, Tehran and the religious authorities in Najaf - have so far stayed out of the proceedings. The Shia leader predicts this situation will continue.

"The strange thing is that Iran and America have not yet intervened, meaning that the game is still purely local, and Najaf has not yet said its word," he said. "So it is difficult to see more than these two scenarios on the horizon."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.