Iraq: How doomed deal with Barzani led to Muqtada al-Sadr’s downfall

The mass resignation of influential Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr’s MPs from the Iraqi parliament was a result of the collapse of his alliance with the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), Iraqi politicians, officials and diplomats have told Middle East Eye.

According to MEE’s sources, Sadr was frustrated after Massoud Barzani, the leader of the KDP, told him that their political partnership - sealed in January after the Sadrists’ breakthrough in last October’s elections - had reached “a dead-end”.

One onlooker, a western diplomat speaking on condition of anonymity, told MEE Sadr’s Iran-backed political rivals had targeted Barzani’s KDP as the weak link in the alliance, driving a widening wedge between the two veteran powerbrokers.

'Sadr was stabbed in the back. His decision to resign and withdraw from the political process was a natural result of that stab'

- western diplomat

The diplomat said: “Sadr was stabbed in the back. His decision to resign and withdraw from the political process was a natural result of that stab.

"The tripartite alliance was fragile and relied mainly on Barzani, so he became a target for all of Sadr's rivals.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"The pressure on the two men was enormous. Barzani began to grumble and finally told Sadr that their alliance was futile.”

But MEE’s sources dismissed speculation swirling since Sadr ordered his 73 MPs to resign on 12 June that he intends to resort to the street and draw on his mass support base to put pressure on his opponents.

Sadr has no intention of escalating the situation against his Iran-backed Shia rivals, despite their role in his downfall, they said.

It remains unclear how the current political situation will unfold, but the main beneficiary of the withdrawal of the Sadrist MPs is the Iran-backed Coordination Framework parliamentary coalition, which stands to gain about 50 seats. Under Iraqi law, MPs who resign are replaced by the losing candidate with the most votes in each constituency.

'The height of his glory'

Sadr’s sudden retreat from parliamentary politics had surprised and confused both his allies and opponents, coming, as one onlooker familiar with the situation described it, “at the height of his glory”.

After the success of his Sairoon Alliance bloc in October’s parliamentary elections, Sadr sought to shake up Iraqi politics by excluding his Iranian-backed opponents from power and ending their two-decade hegemony, rejecting the formula for consensus-based power-sharing governments that have been the norm since Saddam Hussein was toppled in 2003.

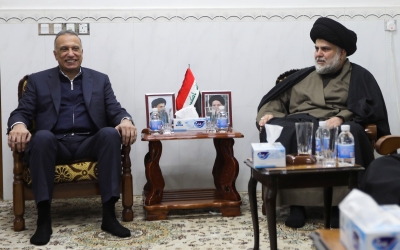

Instead, in late January Sadr formed a tripartite “Save the Homeland” coalition with Barzani’s KDP, the largest Kurdish party, and parliamentary speaker Mohammed al-Halbousi’s Sovereignty Alliance, a Sunni political bloc, securing the support of an absolute majority of 186 out of 329 MPs.

But the Iranian-backed factions hit back by targeting not Sadr but the KDP, the smallest party in the coalition with just 31 seats, and the KDP-led semi-autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Erbil.

The first “resonant” slap, as described by observers, came in February when Iraq’s Federal Supreme Court abolished an oil and gas law that had enabled the KRG to sell its oil and gas separately from Baghdad since 2007.

The court ruled the law unconstitutional and obligated the KRG to deliver oil and extracted natural resources to Baghdad.

Sadr showed no reaction, sources told MEE.

The second slap, which was no less powerful than the previous one, was a missile attack launched from Iranian territory in March which targeted a villa belonging to the executive director of the KAR Group, one of Barzani's key trading partners, in northern Erbil.

The Iranians said the attack targeted a headquarters of Israel’s Mossad spy agency in Erbil.

Sadr contented himself with ordering the creation of a parliamentary fact-finding committee to investigate the claims. The committee announced that it did not find anything, and “Sadr just forgot it”, a KDP leader told MEE.

The March attack was followed by a series of other attacks targeting the offices and interests of a number of KDP leaders in Baghdad and Erbil.

The attacks culminated in the burning of the party's headquarters in Baghdad in late March, and the targeting of a refinery in Erbil in early April.

This time, Sadr published several tweets in which he pointed the finger of accusation at his Shia rivals, the Iranian-backed armed factions, and condemned their attacks on his allies.

A prominent Shia leader opposed to Sadr told MEE: "Barzani was the spearhead of the tripartite alliance. He was the one who persuaded Halbousi and other Sunni leaders to ally with Sadr. But he was also the soft flank of this alliance, and the outlets to reach him [target him] are numerous.

"Sadr's opponents have moved patiently and deliberately, and used the judiciary and other tools to break up the relationship between him [Sadr] and Barzani.

"It became a drain on Barzani and his party. On the other hand, Muqtada wanted them to continue their alliance with him without offering them anything."

Siding with Baghdad

The pressure continued to grow on Sadr and his allies. In a move intended to prevent him from exploiting his control over the government and the parliament, his opponents resorted to the federal court again, obtaining a ruling banning the current caretaker government from submitting law proposals to parliament or making any changes affecting officials in senior positions.

Sadr sought to evade these restrictions, instructing his parliamentary bloc to present a draft law criminalising normalisation with Israel.

The draft law presented Sadr’s opponents with another opportunity to create friction within the coalition as the KRG has, in the past, faced scrutiny over reports of oil shipments to Israel. KRG officials denied dealing directly or indirectly with Israel, and pointed out that oil cargoes often change hands several times before reaching their final destination.

Fearful too that Sadr would get the credit for the legislation, the Coordination Framework joined Sadr’s alliance to vote in support of the law last month.

Meanwhile, Sadr and his bloc were struggling to pass an emergency food security and development law that would provide the current caretaker government with $25bn in surplus oil sales.

The money would have extended the life of the caretaker government, led by Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi, for several more months, giving Sadr more time and space to force his opponents to accept his project, politicians and observers told MEE.

Fearing that the law would be challenged by his opponents in the federal court, Sadr’s MPs named a number of beneficiaries of the law in order “to embarrass the Iran-backed factions in front of their audience and block their way,” a member of the financial parliamentary committee which drafted the law told MEE.

But the gambit backfired: the text of the law also revealed that the Kurdish region would not receive any of the allocated money.

Leaders of the Coordination Framework saw that as "another painful blow to the relationship between Sadr and Barzani," a key leader of the Iranian-backed bloc told MEE.

A prominent Kurdish leader told MEE: "Sadr's Kurdish and Sunni allies felt they were nothing more than tools that Sadr uses to implement what he wants, without paying any intention to what they want.

"The main problem [between the three allies] is that the goals, arenas and ambitions were different, and the coordination between the three leaders [Sadr, Halbousi and Barzani] was close to zero.

'Muqtada used to ask and get what he asked for. As for the rest, they asked, but they didn't get anything'

- Kurdish leader

"Muqtada used to ask and get what he asked for. As for the rest, they asked, but they didn't get anything.”

In KDP ranks, the passing of the emergency food security and development law earlier this month was "clear evidence" for Barzani that Sadr would not line up with the KRG in its dispute with Baghdad over revenues from the region's oil sales.

A senior KDP leader told MEE: "We did not intend to vote on that law. Frankly, we had no interest in voting on it.

“Some of us [KDP leaders] suggested we abstain from voting or boycott the voting session, but we did not.

"It was clear that Sadr would not offer us much regarding the contentious issues with Baghdad, especially with regard to the oil and gas law.”

Resignation letters

On the evening of Wednesday 8 June, Iraq’s parliament approved the emergency food security and development law in the presence of 273 MPs. Most of Sadr’s rivals had voted in support of the law, though voting results have not been published by the parliament.

Hours later, Sadr celebrated what he considered "another victory to be added to the camp of reform”.

He said he would supervise the implementation of the law himself, and that he would not hesitate to expose anyone who "tampered with the people's food”.

The next afternoon, Sadr, without any forewarning, delivered a televised speech, circulated by his office, in which he said he was not seeking power and only wanted to “[preserve] the people’s dignity, security, food, and goodness… So, that Iraq will not once again be a fertile ground for consensus, corruption and dependency”.

Sadr, looking upset and frustrated, concluded by asking his bloc's deputies to write their resignations from the parliament and to wait for his orders to set a date for their submission, "to end the political blockage”, which he said was "fabricated”.

It is unclear what happened in Hananah, Sadr's residence in Najaf, in the 20 hours between the statement celebrating the approval of the law and his instruction to his MPs to pen their own resignation letters.

MEE contacted several of Sadr's office workers and others close to him to find out any details regarding the identities of Sadr's visitors or his movements during those hours, but no one wanted to talk.

But what many overlooked while the Sadrists were celebrating the passing of the food security law was that Erbil was boiling.

What made Sadr quit?

Just two hours after Sadr announced his victory on Wednesday evening, a booby-trapped drone exploded on the main road between Erbil and Bayram town, where the resort of Salah al-Din, Barzani's permanent residence, and a number of diplomatic missions are located.

According to security sources, three people were injured and many cars were damaged. What proved more damaging to Sadr was the response of the KRG.

In an unprecedented move, the region’s security council publicly accused Kataeb Hezbollah, one of the most powerful Shia armed factions and the most hostile to Barzani, of carrying out the operation.

'Muqtada was the master of the scene, but he suddenly left everything and retreated away. He was forced to make this decision. It was not a choice, as his men claim'

- adviser to President Barham Salih

Barzani also issued a strongly worded statement, seemingly directed at Sadr, in which he said "the purpose of this oppressive act is very clear... and expressing protests and denunciations alone is not a solution”.

Instead, Barzani demanded “practical steps" to stop such attacks.

On 12 June, Sadr phoned Barzani to discuss "the latest developments in the political process," according to a very short statement issued by Barzani's office.

The statement did not reveal details of the conversation that took place between the two men, but Sadr ordered his deputies to submit their resignations soon afterwards, politicians told MEE.

A number of Sadrist leaders who were contacted by MEE denied knowledge of any details of what was discussed between Sadr and Barzani.

Kifah Mahmoud, Barzani's media adviser, told MEE Barzani had nothing to do with Sadr's decision, and that what happened was a result of the intra-Shia dispute between the cleric and his Iran-backed rivals.

Mahmoud said: "Perhaps because Sadr failed to impose his will on the Coordination Framework, and to implement his project, he chose to withdraw."

Another KDP leader close to Barzani refused to answer questions regarding any influence that Barzani may or may not have exerted over Sadr.

But he said Sadr's decision “was a result of Sadr's feeling of pressure and frustration".

He continued: “He [Sadr] politically committed suicide. He could have turned into an opposition in the parliament, instead of losing everything."

A prominent Kurdish adviser close to President Barham Salih said Sadr was “forced” to make that decision, and he sought to “save his face” by announcing his withdrawal.

"The secret of Sadr's collapse is the same as the secret of his success. The tripartite alliance is what ended Sadr's political career," the adviser told MEE.

"Muqtada was the master of the scene, but he suddenly left everything and retreated away. He was forced to make this decision. It was not a choice, as his men claim.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.