From triumph to defeat to defiance: A brief history of the Pan-Arab ballad

Ask any Arab who grew up in the 1960s or 1970s about the most patriotic song they remember - one that can still send chills down their spine- and they will likely suggest Al-Watan Al-Akbar (The Greater Homeland).

Performed by artists from Egypt, Lebanon, and Algeria, the opening of this pan-Arab anthem from 1960 surges with a rousing symphonic arrangement, complete with drum rolls and cymbals.

Its bold brass and uplifting strings burst with pride, sparking a sense of grandeur and triumph, punctuated by the accompanying hum of a choir that perfectly captures the zeitgeist: an ascendant Arab identity and an aspiration to match.

Released during the unification of Egypt and Syria under the United Arab Republic (1958-1961), the 11-minute track extolled the virtues of Arab solidarity and nationalism.

In the song, Lebanese crooner Sabah describes Arab unity as a “melody flowing between two oceans, between Marrakech and Bahrain, in Yemen, Damascus, and Jeddah, the same song of the most beautiful unity, the unity of all Arab people”.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

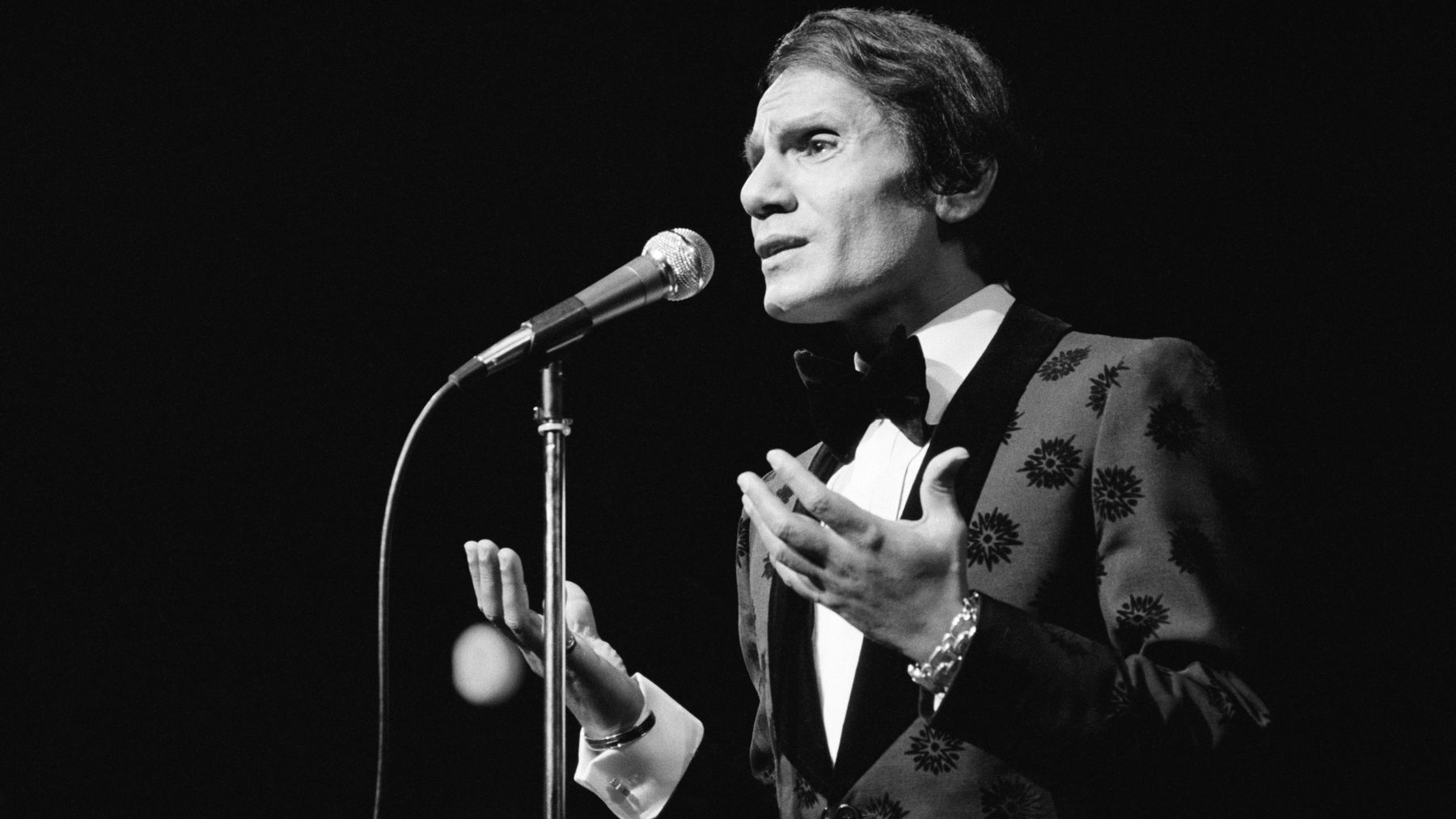

Egyptian Abdelhalim Hafez closes with a promise to free Palestine under the banner of the glorious Arab homeland.

Palestine was the cornerstone of this cultural flourishing and Arab musical productions supporting the Palestinian cause were sensations that enthralled audiences across the region.

Often featuring an ensemble of popular artists, such ballads shaped the Arab narrative on Palestine.

However, as anyone familiar with the current situation in the Middle East would recognise, political dynamics shifted and the prominence of the Palestinian cause in music has declined.

The fragmentation of Arab unity

In 1979, Egypt made peace with Israel following the 1973 October War against the Zionist state.

That peace deal laid the ground for Egypt to regain land in Sinai that was lost in the 1967 defeat popularly known as Al-Naksa (The Crisis), a turning point in popular Arab nationalism.

“Pan-Arabism waned in power as a sentiment, partly due to repressive or otherwise disappointing political outcomes. In contrast, the Islamist revival gained steam,” Sherifa Zuhur, a Middle East scholar, analyst, and author of multiple books on Arab culture, told Middle East Eye.

Between Egypt’s expulsion from the Arab League for normalising relations with Israel and the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1991, the dream of Arab unity dissipated, and with the ensuing first Gulf War, hope and solidarity gave way to despondence.

It would take a decade before the Arab World’s most populous country was readmitted to the Arab League in 1989, two years after the restoration of diplomatic ties with other Arab states.

Simultaneously, between 1987 and 1991 Arab populations witnessed Israel’s brutal clampdown on the first Palestinian intifada, which saw the killing of more than 1,000 Palestinians.

These tumultuous events meant that for a long time, cultural production like Homeland was nowhere to be seen, partly due to growing American cultural hegemony in the region and partly because Egypt, the cultural nexus of the Arab world, was ostracised.

But the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, according to Zuhur, also saw the rise of internationally acclaimed Lebanese composers, singers, and virtuoso oud players Marcel Khalifeh and Charbel Rouhana.

Although their work was not on the scale of Homeland, it was infused with pan-Arab themes, which resonated with audiences across borders, offering sentiments that alluded to a great history, lamented Arab suffering, and stressed the importance of collective resilience.

The resurgence of the pan-Arab anthem

During the 1990s, the Palestinian situation again became a rallying cause for Arab peoples and one that was reflected in cultural output.

Ahmed Al-Arian, an Egyptian producer of Palestinian origin, broke the silence with his score Al-Helm Al-Araby (The Arab Dream).

Released in 1998, the operetta brought together 21 artists from Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, Libya, Kuwait, UAE, Lebanon, Sudan and Jordan.

The piece became especially prominent with the outbreak of the Second Intifada in September 2000, when then-Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon entered Al-Aqsa Mosque despite Palestinian objections.

The stark contrast between Homeland and The Arab Dream cannot be overstated.

A sense of triumph, celebration, and optimism ran through the former, whereas the latter song has a more sombre tone, tentatively dreaming of overcoming the “dark night” a new generation of Arabs had found themselves in.

The song implores listeners to shake off their apathy and in its crescendo, there's a subtle but pointed message to Arab leaders, a poetic nudge that rebukes them for their hesitance in confronting the Palestinian issue.

It includes a plea urging them to take a stand that history will remember: “Justice needs strength to protect it, in life the right to land will not be achieved with words or complaints.”

A decade after the release of The Arab Dream, in 2008 Al-Arian made a comeback song, which he billed as a sequel.

Titled Al-Dameer Al-Araby (The Arab Conscience), the 40-minute operetta was performed by 33 artists representing the majority of Arab countries.

Accompanied by a video featuring archival footage of Arabs being subjected to humiliation and violence, the track makes piercing references to the horrors of the US invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan.

It also deals with the ongoing brutality of the Israeli occupation of Palestine and the Islamophobia spreading across western societies.

The song galvanised popular sentiment around a single Arab-Muslim cause and fed into the rising discontent with autocratic ruling regimes, serving as an early bellwether of the coming “Arab Spring”.

Pan-Arab anthems today

The Arab uprising that began in late 2010 and continues through to this day, marked a permanent divorce between the populations of Arab countries and their governments, reflected in cultural production that was more independent of the state and willing to go its own way.

A major landmark was the signing of the Abraham Accords in 2020, which saw normalisation of relations between Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Morocco, and Sudan with Israel.

The move effectively crushed official support for pro-Palestinian productions in those countries.

However, the collective Arab consciousness has found a way through regardless, spurred on by Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza, for which it faces charges of genocide at the International Court of Justice.

Produced and performed by independent artists, the hit song Rajieen (We Shall Return) reflected a shift in musical taste among younger generations while echoing long-standing pan-Arab sentiments.

Since its release in November 2023, Rajieen has been viewed over 5.8 million times on YouTube alone.

Filmed in Jordan, which signed a peace treaty with Israel in 1994, the song features 25 young artists from across the Middle East and North Africa, highlighting the gaping rift between Arab governments and their citizens.

Describing itself as the “anthem that transcends boundaries, embodying resilience and resistance,” the lyrics feature scathing condemnation of the unfolding genocide in Gaza, expressed with palpable indignation, anger, and defiance.

“Where are the Arab rulers? Where are the leaders?

My brothers and sisters in Gaza are subject to extermination

Only two words: Either "martyrdom" or "victory”

It's time to rise up

How can we declare peace, When Belfour's declaration stands?

Still, my heart is Palestinian in life, in death.”

The eight-minute track samples a range of musical genres like pop, Egyptian folk, and rap and comes across as a call to arms, promising to return triumphantly to the Holy Land while confronting western hegemony, the hypocrisy of world leaders, and Arab capitulation.

“This is part of the legacy of Pan-Arab music supporting Palestine and can be traced back to iconic productions like Al-Watan Al-Akbar and Al-Dameer Al-Araby,” said Zuhur,

“[Rajieen expresses] our feeling and responsibility as Arabs, that this is a personal cause for all of us,” one of Rajieen’s six producers Nasir Al-Bashir, told MEE.

Bashir said that while he faced no production hurdles, publication and distribution posed a huge challenge.

“We faced censorship from many platforms that have the ability to control the narrative [on Gaza] but at the same time all the support we received showed us that… it is difficult to silence a whole people, even if you have some form of authority over a medium,” he explained.

Erin E. Cory, senior lecturer in media and communication studies at Malmo University in Sweden, said that while people have always held the same sentiments on issues like the Palestinian cause, social media has infused them with a sense of urgency to act.

“People knew then, and people know now. The difference is that the entire world has access to the daily unfolding of a genocide,” Cory told MEE.

Zuhur agrees that despite censorship and challenges in voicing pro-Palestine sentiments, social media continues to play an essential role in informing and allowing the public to visualise events on the ground.

“As with mainstream media, it is part of an information war. Despite Israel’s highly-organised state and military control over news, it is losing the information war as the conflict extends,” she added.

Nearly everyone who worked on Rajieen was born after the controversial 1993 Oslo Accords, which Palestinians believe was intentionally designed to fail.

It is said that referring to refugees, Israel’s first Prime Minister David Ben Gurion once said that "the old will die and the young will forget".

Al-Bashir pushes back. “The younger generation’s engagement with this song proves that our elders have not forgotten, and neither have their children,” he says.

Abdullah Nasif wrote this article in collaboration with Egab

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.